4D World (XIII): 5D Spacetime

(Note: If you are still struggling with whether the fourth dimension is space or time, I strongly recommend not reading this article yet, as it will only increase your confusion.)

This time, we will look at the physical laws of the 4D world—or more accurately, the universe containing it: General Relativity in 5D spacetime (4D space + 1D time) and the structure of rotating black holes. I am not a professional physicist; this article merely synthesizes relevant literature to sketch out a general understanding of 5D spacetime. As usual, let’s start with a brief overview of relativity in our real-world 4D spacetime.

4D Spacetime Intro

Concepts like relativity and black holes are indeed difficult to grasp; this introduction might take up half the article… I will try to stick to the core “mechanics.” If you don’t want to learn about relativity, you can jump straight to the 5D Black Hole Section. There are many renders there, as well as Black Hole Voxel Rendering links on Tesserxel—just click the Black Hole and Black Ring scenes in the top right.

Special Relativity

Relativity in our world is divided into Special and General. The core premise of Special Relativity is: The speed of light is measured the same in all reference frames. Whether you chase light or run towards it, it still approaches or recedes at the same speed. How is this possible? It can only happen if, at high speeds, space contracts and time dilates to keep the speed of light constant. While these spacetime scaling transformations are counterintuitive, they are described more naturally by the geometry of Minkowski Space: in this space, distance measurement is strange—the Pythagorean theorem becomes the difference of squared sides, and the most symmetric “circle” becomes a hyperbola. See the previous article “Minkowski Space and Constant Curvature Spaces” for details. In relativity, velocities don’t add up directly; instead, they add like hyperbolic angles (called rapidity). Understanding Special Relativity through Minkowski geometry isn’t hard, and there are plenty of visualization resources on the Internet.

Gravity as Curvature

Special Relativity describes flat spacetime without gravity, where physics obeys “Lorentz” symmetry. However, Einstein discovered that gravity isn’t a “force” acting within Minkowski space, but a geometric effect: matter causes Minkowski spacetime to bend, and this curved spacetime guides the paths of objects. In mathematical terms, matter and energy (including electromagnetic fields) are characterized by the energy-momentum tensor, while the curvature of spacetime is described by the Riemann curvature tensor. By comparing the form of Newtonian gravity with the structure of the energy-momentum tensor, Einstein proposed his famous field equations, linking matter distribution to the distribution of curvature.

Spacetime Curvature

While Special Relativity studies flat spacetime, General Relativity studies curved spacetime. This curvature manifests as an effect on distances and angles between objects. The simplest example of spatial curvature is a plane versus a sphere: a plane is flat, a sphere is curved. However, the curvature in General Relativity is different. It treats three spatial dimensions plus one time dimension as a unified 4D spacetime. If the universe were a sheet of paper, the paper would be 4D, with points representing “events.” Spacetime (the paper) curves near massive objects, while remaining flat far away in both space and time directions.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Curvature

Our intuition suggests that low-dimensional objects must exist in a higher-dimensional space to curve. In this view, our 4D spacetime universe would need to sit in at least a 5D space to be curved. However, curvature can be intrinsic or extrinsic. While extrinsic curvature follows that intuition, the curvature in General Relativity is intrinsic. Here is the difference:

- Imagine you have a high-tech flexible-screen phone running a 2D shooter game. Let’s treat the game world as a universe (2D space + 1D time). If we ignore time and focus on space: the screen can be rolled into a cylinder. This doesn’t change the game’s internal logic (physics), However, we would observe that the entire 2D game world has indeed curved within the 3D world, and the physical laws of that world seem to have changed: the trajectories of game bullets are no longer truly straight; instead, these lines become curves as the screen curls (obviously, bullets cannot fly out of a flexible screen). The game characters (NPCs) would have no idea the screen is rolled; they cannot detect this extrinsic curvature. We could even poke a hole in the screen without affecting the game’s internal logic! Could our universe be “rolled up” without us knowing? Actually, extrinsic curvature is physically meaningless in this context. There’s no need to assume a “God” exists outside our universe to fold it.

- However, if the NPCs measure the sum of angles in a triangle and find it is greater than 180 degrees, it implies they do not live on a plane, but perhaps a sphere. This is an intrinsic curvature effect they can measure internally. If you live in a universe where triangles exceed 180 degrees and you return to your starting point by walking in one direction, you are likely in a spherical universe. The “interior” or “center” of the sphere is meaningless to you. Intrinsic curvature is what truly matters, which is why we simply call it a spherical universe.

Back to 4D spacetime: “Universe” means the sum total of all space. Black holes affect the flow of time and the perception of space-time angles—these are purely intrinsic effects. Unless we can observe something outside our universe, a higher dimension is a redundant hypothesis. According to “Occam’s Razor,” we should discard unnecessary assumptions and believe that a 5th spatial dimension does not exist (Note: This is excluding String Theory, which suggests microscopic “curled up” dimensions).

4D Black Holes

Einstein’s equations are highly non-linear and difficult to solve. However, physicists found several classic solutions in the 20th century:

- Schwarzschild Solution: The first black hole solution, describing a non-charged, non-rotating, spherically symmetric black hole. It has a spherical event horizon and a central singularity.

- Reissner-Nordström Solution: Covers charged black holes. Unlike the Schwarzschild black hole, it has an inner and outer horizon. Between the two, motion is one-way, but inside the inner horizon, one can move freely again.Optional Reading: Naked Singularities and Cosmic Censorship

If a black hole has enough charge, the inner and outer horizons approach each other and eventually vanish. The one-way region disappears, exposing the singularity to our universe. A naked singularity is problematic because physics loses its predictive power near it. Penrose proposed the Cosmic Censorship Hypothesis: nature does not allow naked singularities to form. - Kerr Solution: Describes rotating black holes. This is more complex: it has inner/outer horizons and an ergosphere (bounded by the static limit surface). In the ergosphere, you can technically escape, but you cannot stand still; you are dragged along with the black hole’s rotation. The center is not a point but a ring singularity. Mathematically, one could pass through the ring into another “universe” (a wormhole structure), though real physical perturbations would likely cause such structures to collapse. For a non-technical journey through a Kerr black hole, check out Hadroncfy’s article “Voyage to the Black Hole”.

- Kerr-Newman Solution: The most general black hole, both charged and rotating. The No-Hair Theorem states that black holes are characterized only by mass, angular momentum, and charge. They don’t have “texture” or “mountains.”

Metric: To Describe Curvature

Black holes have some properties that are very fascinating and hard to understand. For instance, when you watch an object fall into a black hole from afar, it seems like it never falls in! You will observe that the flow of time for an object approaching the event horizon gets slower and slower. However, from the object’s own perspective, it falls into the black hole within a finite amount of time, and it feels nothing unusual at the moment of crossing. Yet, once it crosses the event horizon of the black hole, conventional concepts of space and time are inverted: the time direction begins to be restricted like space, while the originally spatial radial direction inevitably flows “inward”. In other words, you can no longer stay still or escape outwards, because “outwards” has become an impossible spatial direction. It is difficult to understand the laws of motion inside a black hole using everyday experience; to think clearly, one must learn the language describing spacetime—the metric.

The metric is used to determine how distances are measured at various points in spacetime. Here, I will introduce some technical details; knowing how to take derivatives and total differentials is sufficient, and there is no need to understand differential geometry. Since curved spacetime is locally flat, we only need to describe the calculation method for infinitesimal lengths, and the length of any curve can be obtained by integration. Here are a few examples:

- Plane: This is the Euclidean geometry we are familiar with. The Pythagorean theorem is the metric of the plane: $$ds^2=dx^2+dy^2$$

- Sphere: The square of a small hypotenuse on a unit sphere is not the square of longitude ($\phi$) plus the square of latitude ($\theta$), but: $$ds^2 = d\theta^2+\sin^2\theta d\phi^2$$

- Flat Spacetime: The square of the length in the time direction is negative (taking the speed of light $c=1$, same below): $$ds^2=dx^2+dy^2+dz^2-dt^2$$

What specific information can the metric tell us? With the metric, we can calculate whether the squared length of a vector is positive or negative. If it is greater than 0, the direction is spacelike, i.e., purely spatial; if less than 0, it is timelike, i.e., a temporal direction (the spacetime trajectories of massive objects are always timelike); if equal to 0, it is the trajectory of a photon. The standard term for a spacetime trajectory is worldline. When gravity curves spacetime, objects moving without external forces will deviate from straight motion due to curvature effects. This special trajectory (worldline) is called a geodesic. A geodesic can be understood as the straightest possible curve in curved space. For example, geodesics on a sphere are great circles passing through the center.

The Black Hole Interior

To truly understand the spacetime inside a black hole, one must understand the metric inside. Rest assured, we won’t actually cover the relevant calculations, just a simple look at the expression of the Schwarzschild spacetime metric (taking speed of light $c=1$, gravitational constant $G=1$, same below): $$f(r)=1-{2M\over r}$$$$ds^2=-f(r)dt^2+ f(r)^{-1} dr^2 + r^2(d\theta^2+\sin^2\theta d\phi^2)$$

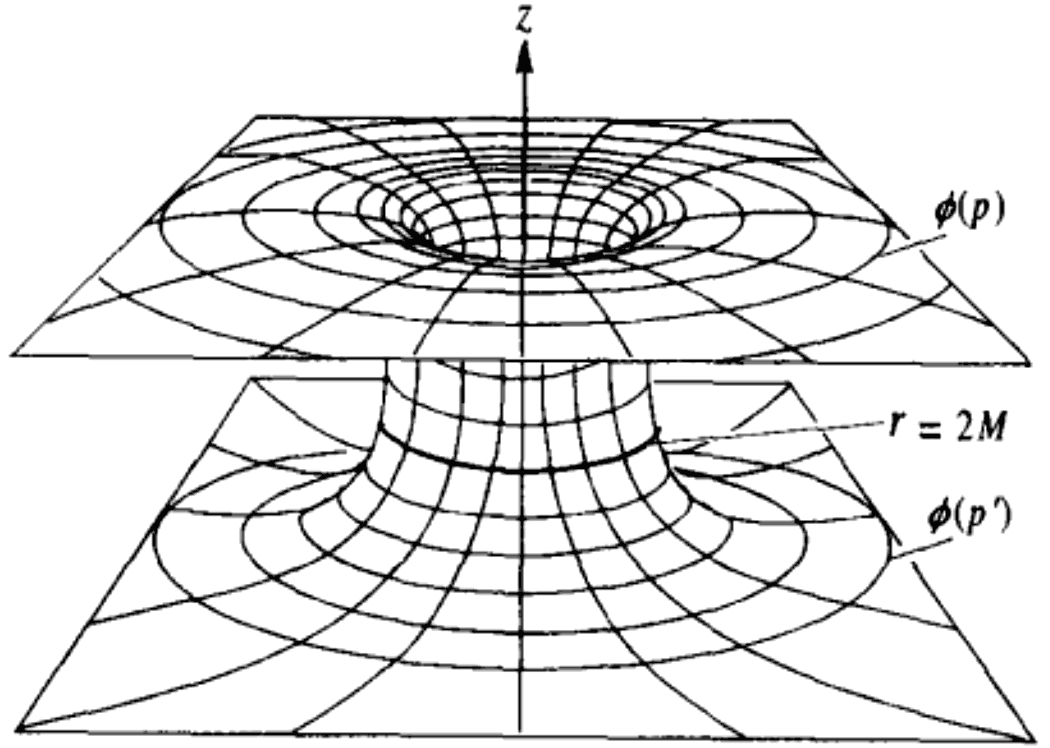

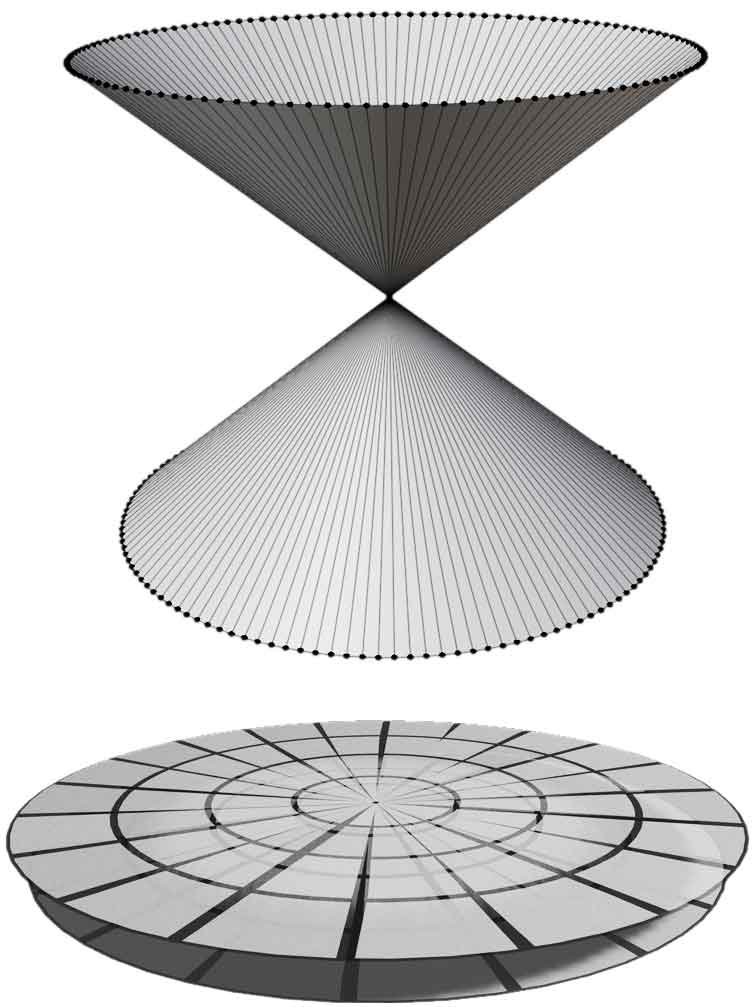

In the Schwarzschild metric, the first two terms reflect the relationship between the flow of time $t$ and the radius $r$, i.e., the spacetime distortion in the radial direction. The latter $r^2$ term is the normal metric of a sphere with radius $r$, showing no distortion in the spherical direction. There are two strange aspects: first, $r$ is in the denominator, causing infinite divergence at $r=0$; second, when $r=2M$, the coefficients in front of $dt^2$ and $dr^2$ become 0 and infinity. If we momentarily ignore time and only calculate the spatial curvature around the black hole, and then compress one spatial dimension, we will find it matches the intrinsic curvature of the surface often used in popular science books to describe the shape of spacetime around a black hole:

The radius of the narrowest “throat” here is the place where $r=2M$. It seems we cannot proceed further into the black hole, but that is not the case. Through appropriate coordinate transformations, a coordinate system can be found that covers the entire spacetime including inside and outside the black hole at $r=2M$, except for $r=0$. We say the place $r=2M$ is merely a coordinate singularity.

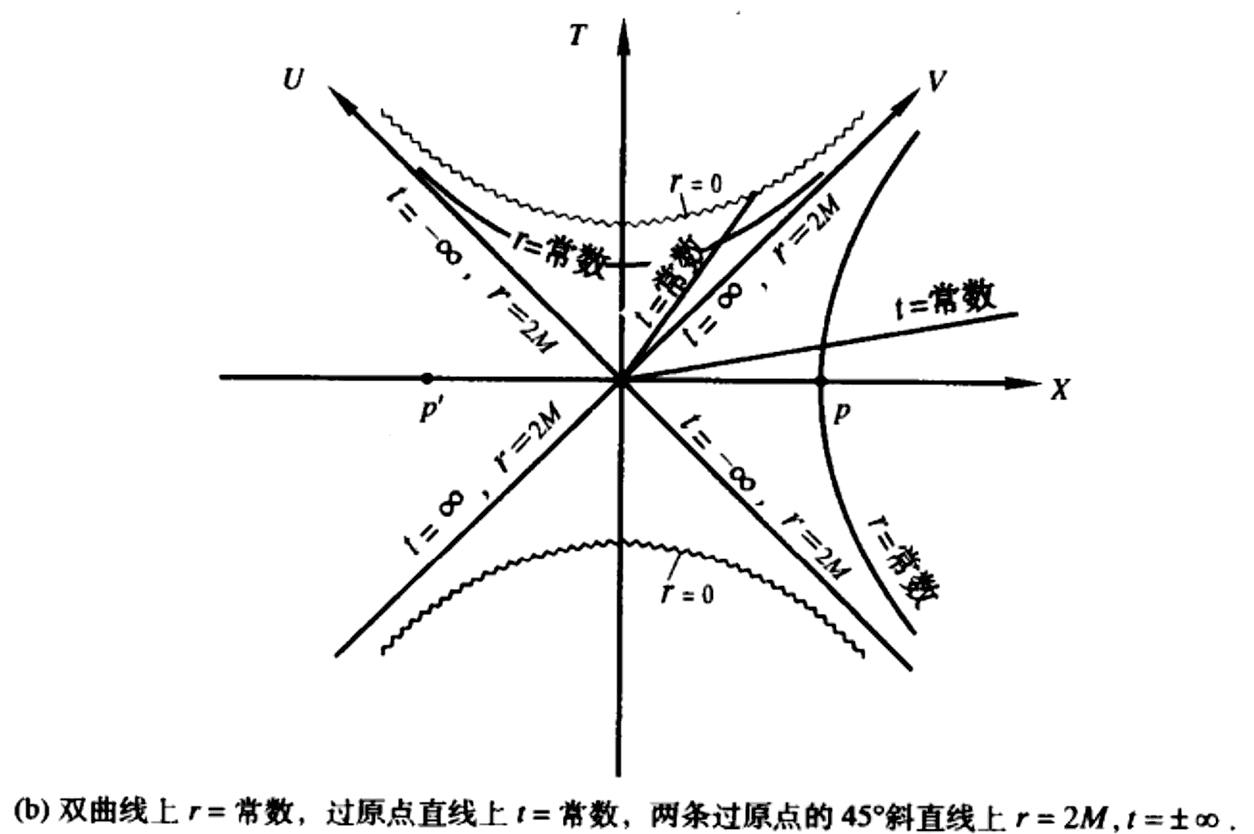

You might ask: clearly in the figure just now, the region $r<2M$ is a hole (void), so how can coordinate transformation conjure something inside? The answer is: the previous figure ignored the time coordinate. When the time coordinate is added, entry is possible. Below is the maximal extension of the Schwarzschild black hole: the Kruskal extension—transforming $(r,t)$ to $(X,T)$ via coordinate transformation, leaving $\phi, \theta$ on the sphere unchanged: $$({r\over 2M}-1)e^{r/2M}=X^2-T^2$$$$\tanh(t/4M)=T/X$$Ignore the complex coordinate transformation above, just look at the X-T spacetime diagram under the new coordinates: (We only drew the first two coordinates, the two angles on the sphere are omitted here) The wormhole-like figure just now actually corresponds to the $X$ axis in the X-T spacetime diagram: The $r$ values on the $X$ axis are indeed all greater than or equal to $2M$, and that narrowest throat corresponds to the origin. So this is not a wormhole linking two universes, because the two sides represent two universes with no causal connection: One benefit of X-T coordinates is that 45° diagonal lines are lightlike geodesics. Although other geodesics are not necessarily straight (except lightlike ones), it is easy to distinguish light rays, timelike, and spacelike lines. The X axis is definitely spacelike, and the T axis is timelike. Timelike worldlines starting from the universes on both sides of the X axis can at most cross the diagonal U/V axes (corresponding to the horizon) to meet inside the same black hole, but cannot meet in the normal spacetime outside. Note that the diagonal U/V axes divide spacetime into 4 regions. The region inside the negative T semi-axis where $r<2M$ also has a singularity at $r=0$, called the white hole region: light inside only goes out and never in, opposite to the black hole region. Although the black hole and white hole are drawn together top and bottom here, like the left and right universes, there is no causal connection, so there is no saying that a black hole must have an accompanying white hole. This extended spacetime only represents a mathematical possibility. It is generally believed that white holes violate thermodynamic laws and cannot exist.

The $r$ values on the $X$ axis are indeed all greater than or equal to $2M$, and that narrowest throat corresponds to the origin. So this is not a wormhole linking two universes, because the two sides represent two universes with no causal connection: One benefit of X-T coordinates is that 45° diagonal lines are lightlike geodesics. Although other geodesics are not necessarily straight (except lightlike ones), it is easy to distinguish light rays, timelike, and spacelike lines. The X axis is definitely spacelike, and the T axis is timelike. Timelike worldlines starting from the universes on both sides of the X axis can at most cross the diagonal U/V axes (corresponding to the horizon) to meet inside the same black hole, but cannot meet in the normal spacetime outside. Note that the diagonal U/V axes divide spacetime into 4 regions. The region inside the negative T semi-axis where $r<2M$ also has a singularity at $r=0$, called the white hole region: light inside only goes out and never in, opposite to the black hole region. Although the black hole and white hole are drawn together top and bottom here, like the left and right universes, there is no causal connection, so there is no saying that a black hole must have an accompanying white hole. This extended spacetime only represents a mathematical possibility. It is generally believed that white holes violate thermodynamic laws and cannot exist.

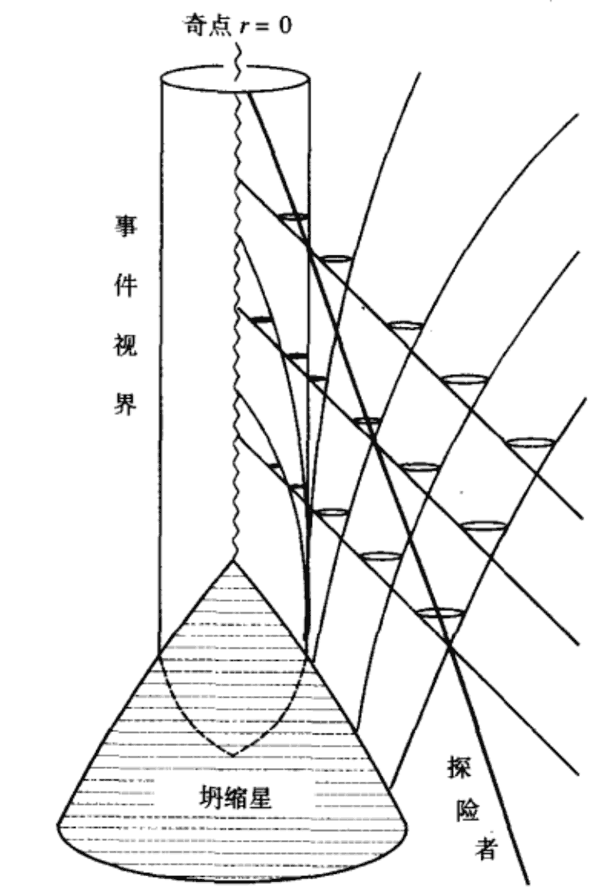

Let’s look at the specific spacetime coordinates again: the original time parameter $t$ corresponds to something like a hyperbolic angle in X-T coordinates, and radius $r$ corresponds to the distance of hyperbolas (but not proportionally). Why do we say time and space swap inside a black hole? Because when $0 < r < 2M$, the signs of the coefficients in front of $dt$ and $dr$ are exactly reversed. Actually, it’s not that mysterious: it’s just that the coordinate system we chose is poor. This diagram indeed shows that after $r<2M$, the $r$ direction changes to the time direction. We can understand the space-time swap this way: actually, there is no rule that letters $r$ and $t$ must be radius and time; they are just a specific set of chosen coordinates. The original $t$ coordinate can be thought of as the time flow seen by an observer at infinity. Since the interior of the black hole no longer has a causal connection with the outside, theoretically any linearly independent vectors can be chosen as coordinate bases; we don’t need to obsess over how the swap happens. However, on the other hand, the $r$ direction is indeed related to radius: the metric of the spherical $\phi, \theta$ coordinates ignored just now shows that even if the $r$ direction becomes timelike, the radius of this sphere is still $r$. That is to say, as time passes along the $r$ direction, one will find the equal-time surface ($r$ is constant) shrinking, until it shrinks to 0 at the singularity. However, the singularity extends infinitely in the spatial direction (the original $t$ coordinate, now spacelike). Actually, there is another inward Eddington coordinate that allows seeing more intuitively that light cannot escape the black hole: the diagram marks the light cone, showing that entering the black hole, the entire light cone will shrink to the singularity at $r=0$.

Introduction to the Kerr Metric

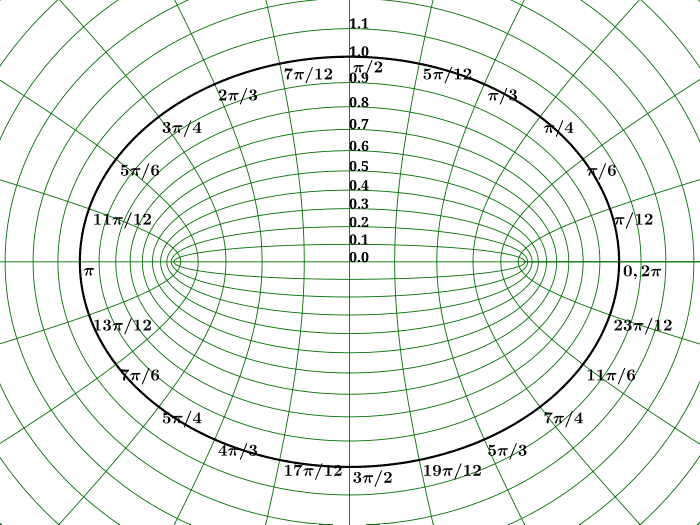

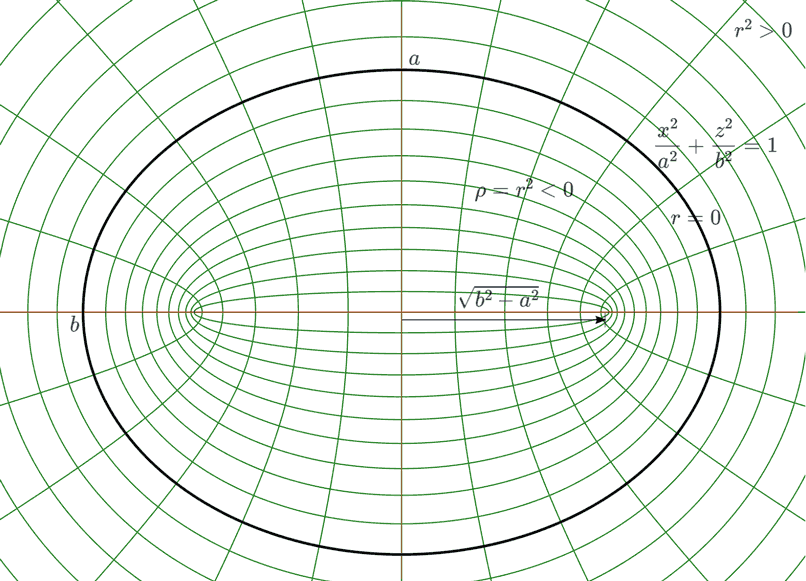

Here I introduce some properties of the rotating black hole (Kerr metric) to pave the way for the five-dimensional rotating black hole later. The Kerr metric expression is a bit complex, so it is not given here. If we let the mass M in the Kerr metric equal 0, logically we should get flat spacetime. But comparing with the spherical coordinate expression of flat spacetime, we find that the spatial part of the Kerr metric at this time is not the metric expression of 3D spherical coordinates, but a metric of ellipsoidal coordinates, accurately called oblate spheroidal coordinates. It can be derived from rotating 2D elliptic coordinates. The 2D elliptic coordinate system consists of a series of confocal ellipses and hyperbolas, where a parameter $r$ can range from $0$ to positive infinity, and constant $r$ lines are ellipses, meaning $r$ roughly corresponds to the size of the ellipse. Another parameter $\theta$ can take values from $0$ to $2\pi$, similar to polar coordinates.

Now let’s rotate and elevate the elliptic coordinates: after rotating around the minor axis of the ellipse, we get oblate spheroidal coordinates: introduce a third parameter $\phi$ to represent this rotation angle similar to longitude. The original $\theta$ angle is now similar to latitude, taking values only between $0$ and $\pi$. The original hyperbolas become hyperboloids of one sheet after rotation. The coordinate surface of the third parameter $\phi$ is a half-plane around the rotation axis. Note that when $r=0$, the original ellipse shrinks into a line segment connecting the two foci, which becomes a disk after rotation. Kerr metric calculations show that in the case with mass, the curvature is infinite only at points satisfying both $r=0$ and $\theta=0$, meaning only the edge of the focal disk has singularity, constituting the ring singularity of the black hole. By the way: analysis of the metric shows that the shapes of the two horizons are not spheres, but surfaces of constant $r$, i.e., ellipsoidal. The boundary of the outer ergosphere—the infinite redshift surface—has an $r$ value related to $\theta$, largest at the equator and smallest at the axis, and tangent to the outer horizon.

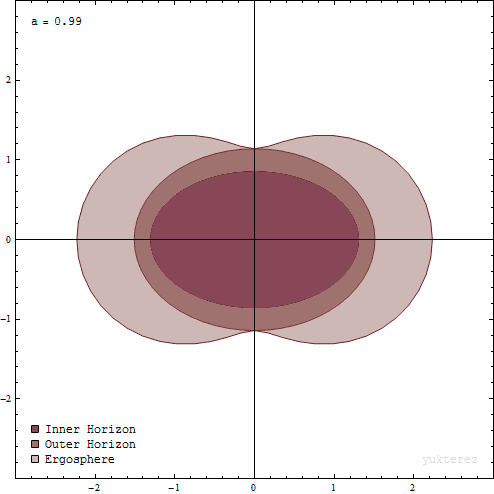

Many illustrations of Kerr black hole structures mistakenly interpret $r$ as the radius in spherical coordinates, drawing the two inner horizons as perfect spheres and the infinite redshift surface as an ellipsoid. This is wrong. The true shape of the infinite redshift surface drawn in oblate spheroidal coordinates is a bit irregular, concave like a red blood cell.

(Optional Reading) To smoothly understand 5D rotating black holes and high-dimensional ellipsoidal coordinate series later, let’s look at various ellipsoidal coordinate systems:

- The oblate spheroidal coordinate system obtained by rotating around the minor axis of the ellipse, as introduced, has the specific form (where $a$ is a constant representing focal length):$$\begin{align} x&=\sqrt{r^2+a^2}\sin{\theta}\cos{\phi} \\ y&=\sqrt{r^2+a^2}\sin{\theta}\sin{\phi} \\ z&=r\cos{\theta}\end{align} $$

- Rotating around the major axis of the ellipse yields another prolate spheroidal coordinate system: unlike the oblate one, the original hyperbolas become hyperboloids of two sheets. The specific form is:$$\begin{align} x&=r\sin{\theta}\cos{\phi} \\ y&=r\sin{\theta}\sin{\phi} \\ z&=\sqrt{r^2+a^2}\cos{\theta}\end{align} $$

- There is also the most general ellipsoidal coordinate system where all three axes are unequal: its three coordinate surfaces are triaxial ellipsoids, hyperboloids of one sheet, and hyperboloids of two sheets. Ellipsoidal coordinates cannot be obtained by rotating 2D coordinates, but spherical coordinates, prolate spheroidal coordinates, and oblate spheroidal coordinates can all be seen as limit forms of this coordinate system. See Wikipedia for details.

Here is the translation of the provided content, retaining the original Markdown structure and HTML tags.

5D Schwarzschild Black Hole

We can obtain five-dimensional spacetime simply by adding one spatial dimension to four-dimensional spacetime. When the black hole is not rotating, its structure is similar to the 4D Schwarzschild black hole, except the inverse term regarding $r$ in the metric becomes an inverse square. Furthermore, 5D General Relativity is compatible with Newtonian mechanics under the low-speed approximation. This paper demonstrates that the decay index of gravitational force outside a planet predicted by General Relativity in N-dimensional space is consistent with calculations using the flux conservation hypothesis. That is, under the weak field approximation of General Relativity, the gravity of an object in 4D space (5D spacetime) still decays according to the inverse cube law.

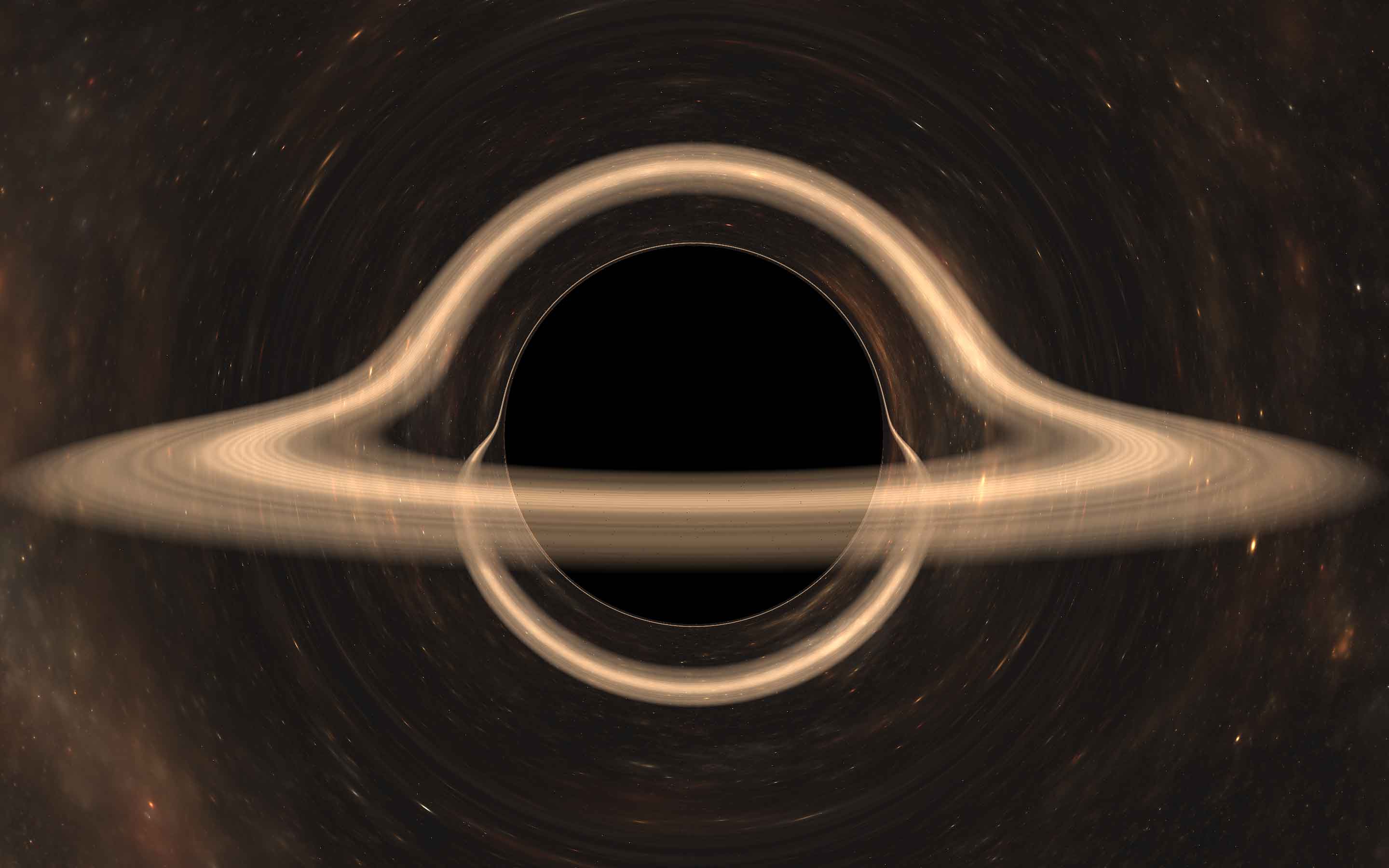

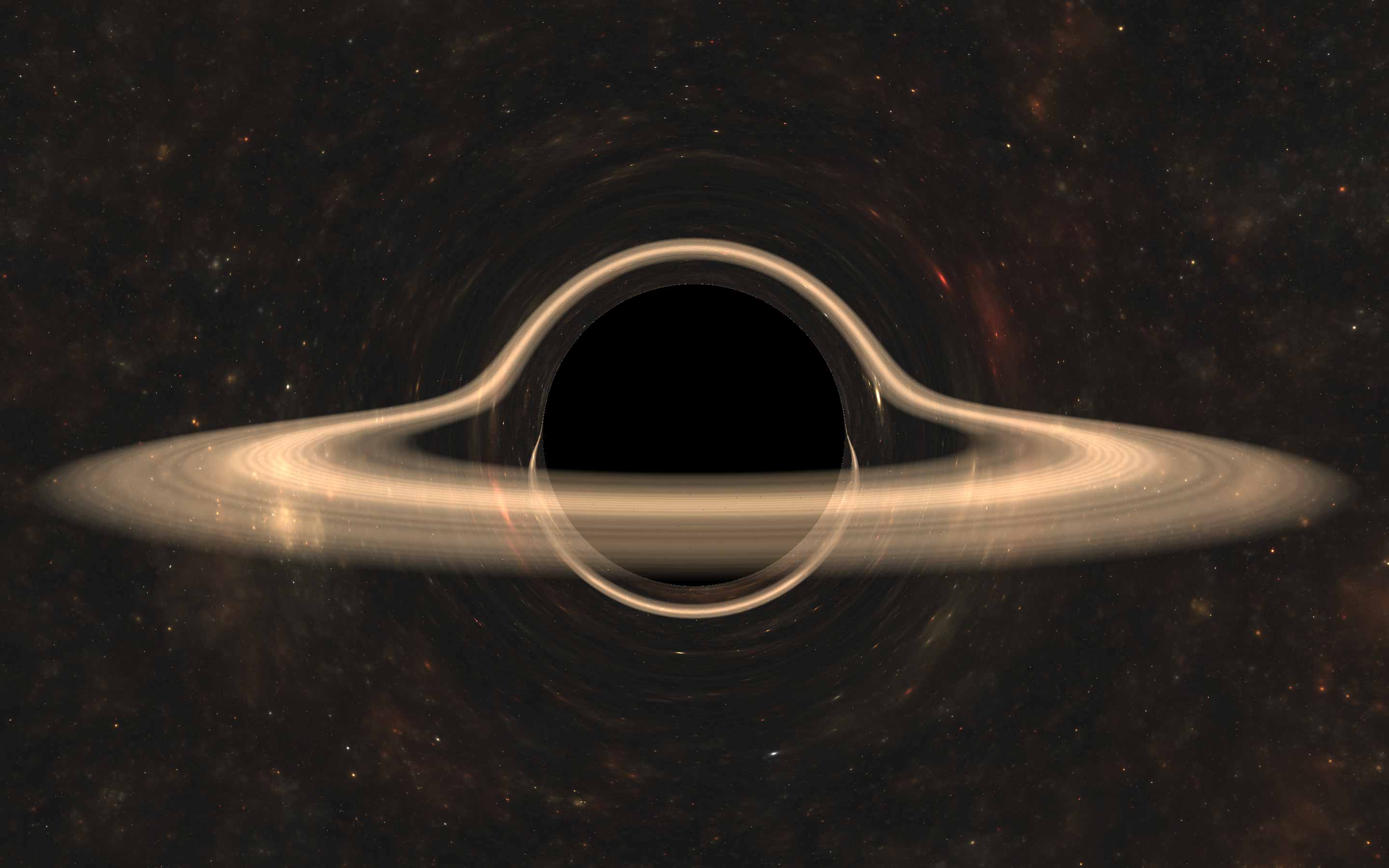

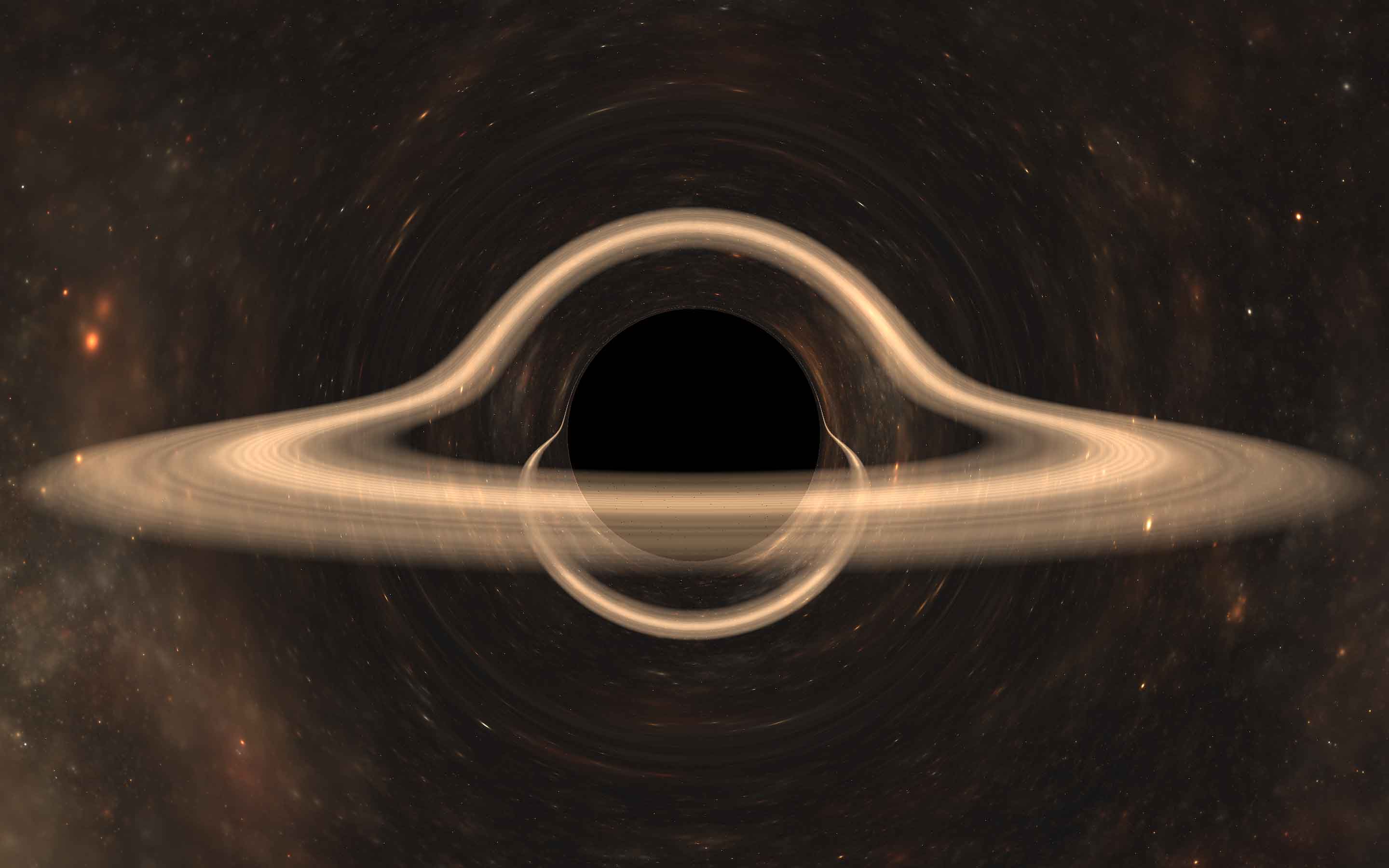

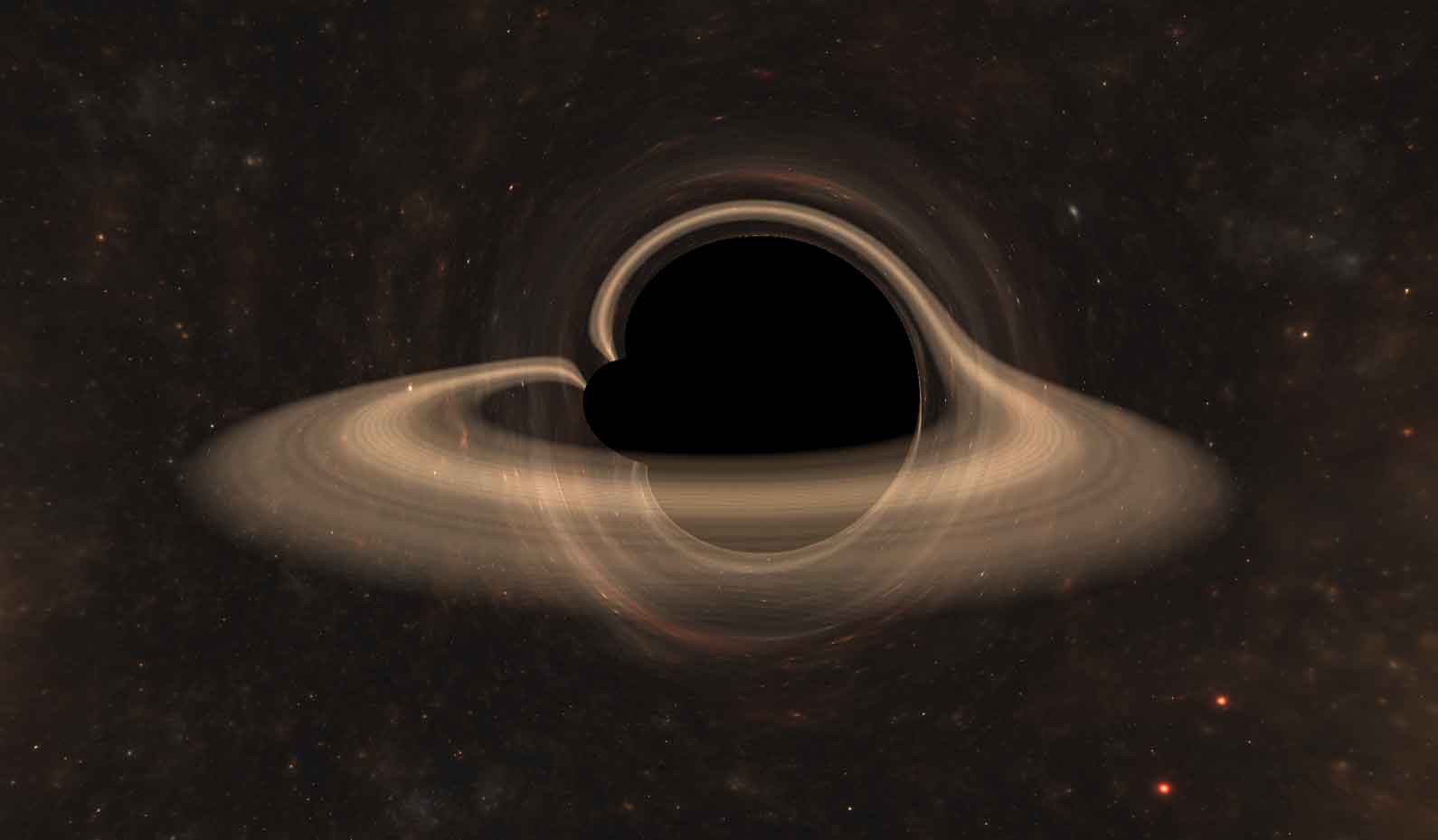

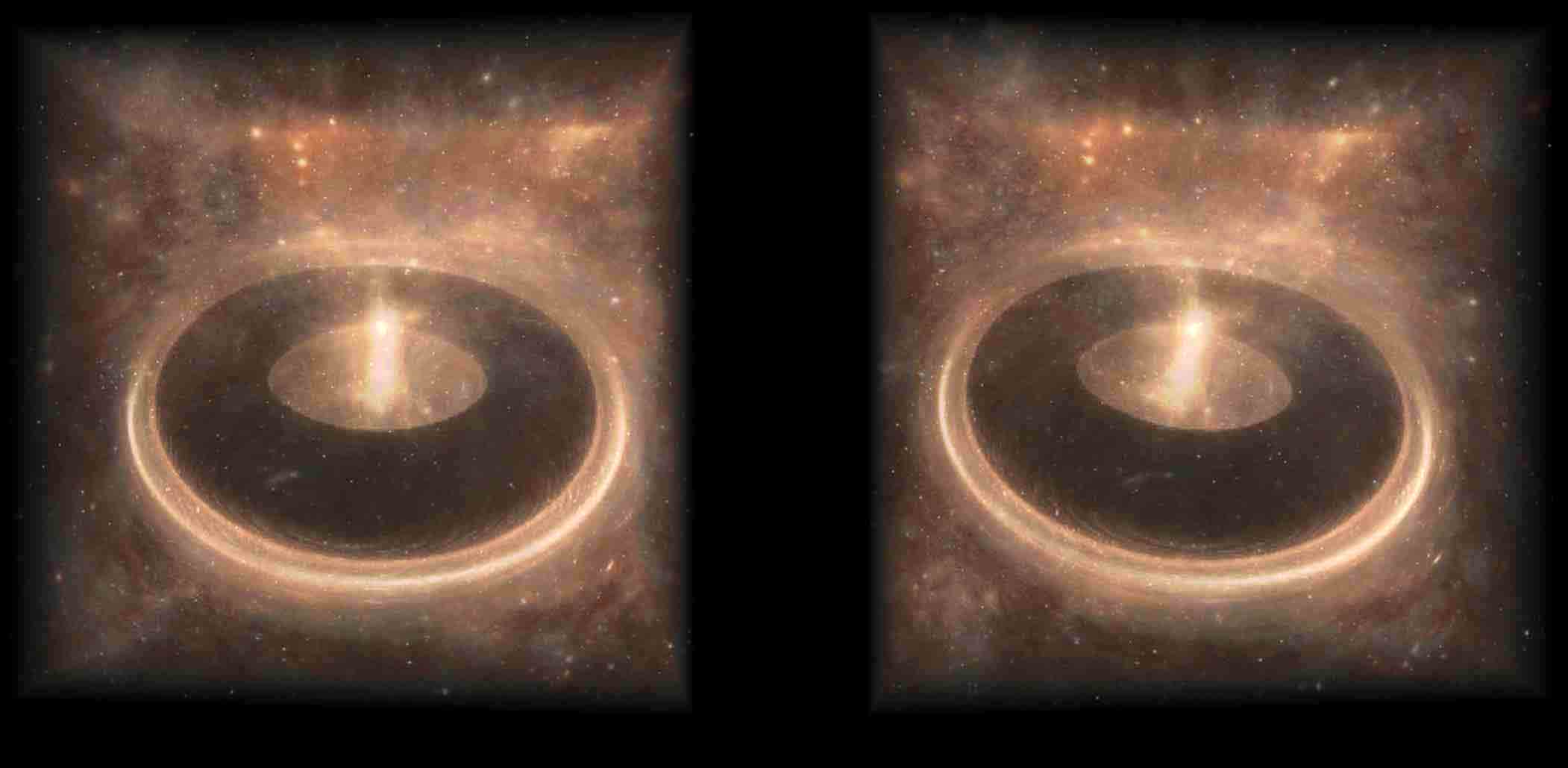

The formula for a 5D Schwarzschild black hole isn’t too complex. I wrote a small WebGPU ray-tracing program to compare the visual differences between 4D and 5D black holes. In the images below, the camera is located at $r=3$, and the accretion disk ranges from $r=1$ to $r=2$. I first rendered the 4D and 5D cases with a Schwarzschild radius of 0.3, finding that the 4D black hole looks slightly larger than the 5D one:

I interpret this as 5D gravity decaying faster, unable to control more distant regions, thus appearing smaller. The comparison below is even more obvious: I rendered a 4D black hole with a radius of only 0.2 and compared it again with the 0.3 radius 5D black hole. I found that while the black region in the 5D image is larger than in the 4D image, the thickness of the semicircle on the accretion disk (after light deflection by the black hole) is actually larger in the 4D case than in the 5D case. This might be a manifestation of the ability to deflect light at the periphery of the black hole.

Note 1: Theoretically, 5D black holes do not have stable accretion disks, and the starry sky is also very sparse. Therefore, in a “real” 4+1 dimensional universe, stars are few and far between, and the area around a black hole is pitch black, nearly invisible. I used a background similar to our universe’s starry sky just for aesthetics (3D/4D starry skies were procedurally generated by my modification of Star Nest on Shadertoy), and added a spherical-disk accretion disk.

Note 2: Here I used the Hamiltonian equations recommended by ChatGPT to calculate the light bending of 4D and 5D Schwarzschild black holes, and the AI also helped me complete the derivation of key formulas. There is a flaw here: there is a coordinate singularity near the polar axis of spherical coordinates, leading to numerical instability, so the generated image has a flawed line. To eliminate it, the step size must be reduced, increasing rendering time and making it very laggy. Getting a high-quality image takes about 10 seconds, so there is no real-time interactivity.

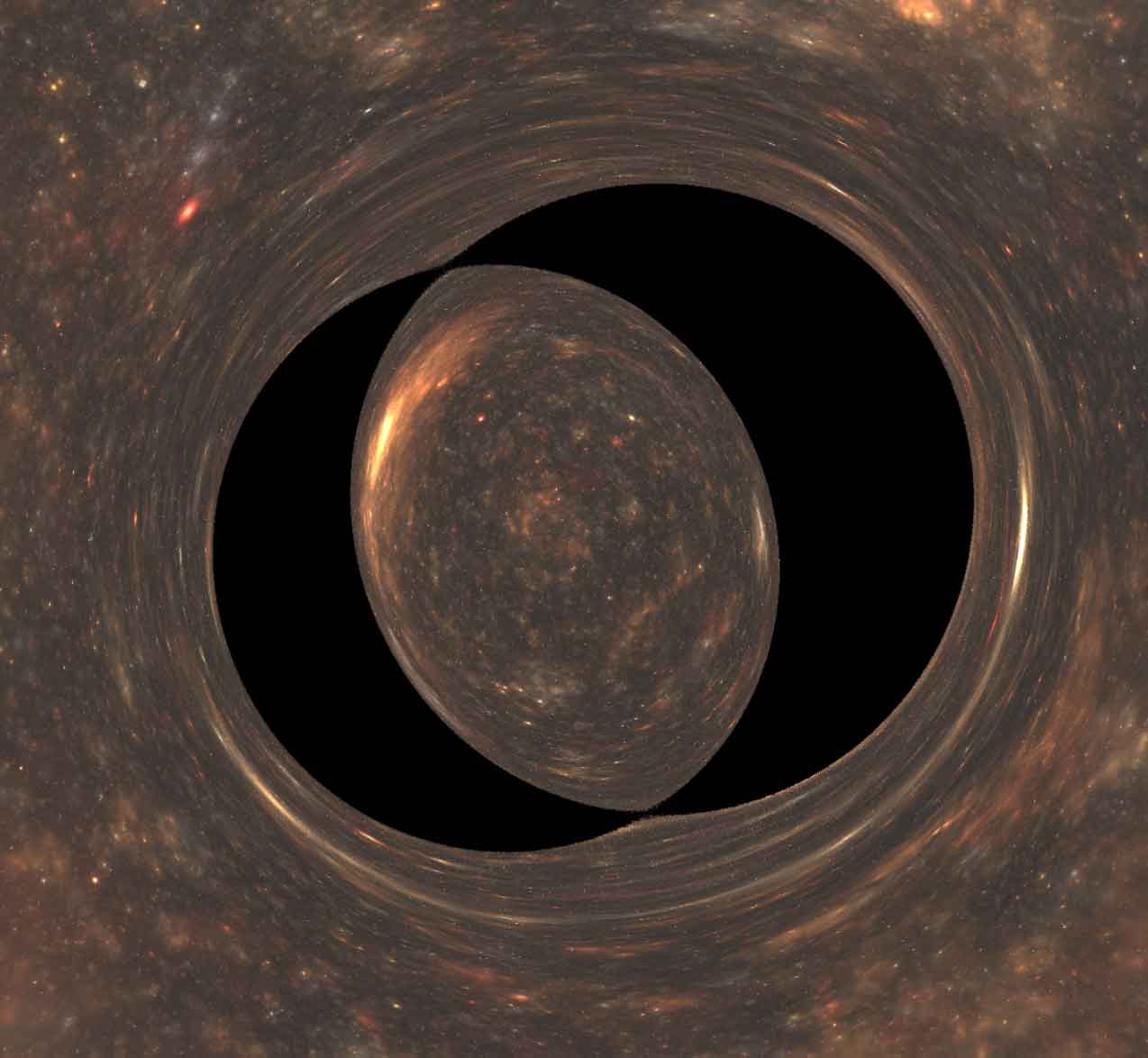

Later, I heard from CFY that there is a cheat method for rendering Schwarzschild black holes: one can introduce an “effective potential” and treat photons as particles moving in a central potential field similar to Newtonian mechanics, which yields the same results as tedious differential geometry calculations. Thus, we have the opportunity to perform real-time voxel rendering of a 5D black hole! Below is the 5D black hole rendered using my Tesserxel engine. In this screenshot, the black hole distorts the image of a star directly behind it into a spherical shell—a higher-dimensional version of an Einstein ring. Here I added a more “realistic” circular accretion disk (ignoring its instability), resulting in the black hole’s accretion belt appearing as only a small rod-like section in the cross-sectional view.

Link here, click on the Black Hole scene in the top right corner.

Aside from this, the 5D black hole doesn’t look much more special than the 4D one visually. However, there is double rotation in 4D space, so it is conceivable that the structure of a 5D black hole should be richer than that of a 4D Kerr black hole.

Myers-Perry Black Hole

The 4D Kerr rotating black hole solution can be analogized to arbitrary n dimensions; this rotating black hole solution is called the Myers-Perry black hole metric. Here is the paper link. Below we focus on the structure of the 5D rotating black hole.

I didn’t read that paper carefully at first, but I preliminarily guessed that the single rotation case should be very similar to the 4D Kerr black hole: an outer ergosphere/static limit, inner and outer horizons in the middle, and a one-dimensional ring singularity inside following the direction of rotation. What about the double rotation case? What about the most special isoclinic double rotation case?

Starting from a single-rotation black hole, if we slowly superimpose rotational angular velocity in its absolutely perpendicular direction, how will the black hole’s structure change? I initially made some incorrect guesses. Interested readers can click here to expand and view my guess process.

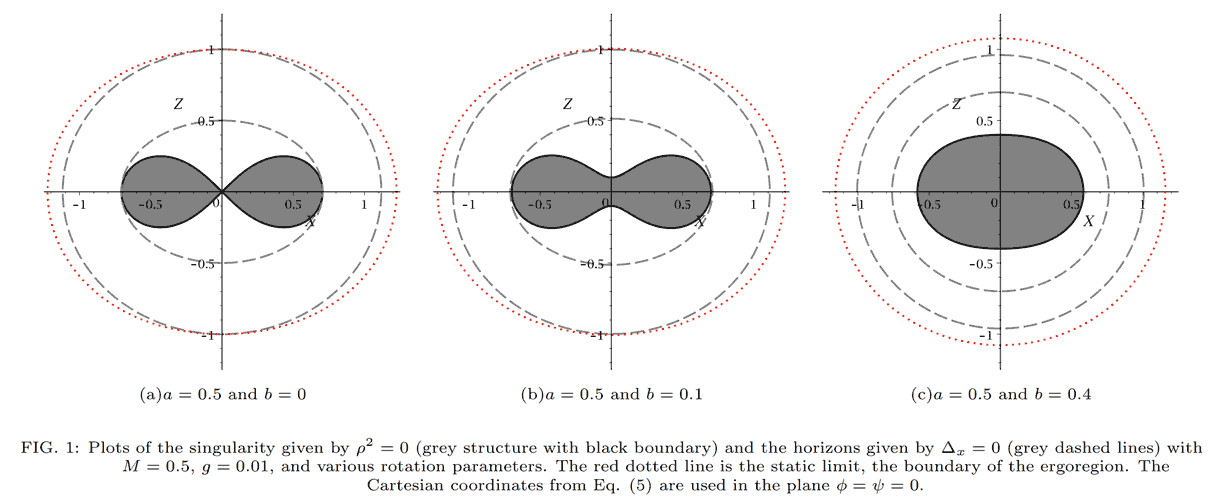

To truly analyze this problem clearly, we should analyze what the flat coordinate system looks like when the mass is 0 in the Myers-Perry black hole metric, just like with the Kerr black hole. Calculation and verification reveal that, given size parameters $a$ and $b$ related to the two angular momenta, the Myers-Perry metric is actually flat space with the following coordinate transformation: $$\begin{align} x&=\sqrt{r^2+a^2}\sin{\theta}\cos{\phi_1} \\ y&=\sqrt{r^2+a^2}\sin{\theta}\sin{\phi_1} \\ z&=\sqrt{r^2+b^2}\cos{\theta}\cos{\phi_2}\\ w&=\sqrt{r^2+b^2}\cos{\theta}\sin{\phi_2}\end{align} $$Obviously, $r=0$ corresponds to a hyper-ellipsoid with four axes $a$, $a$, $b$, $b$. As long as $r$ is not 0, the coefficients in front are larger, indicating that these hyper-ellipsoidal coordinates only cover the exterior of the $r=0$ four-axis hyper-ellipsoid. This suggests our choice of coordinates isn’t great: although $r^2$ cannot be negative, there is no reason restricting us from making the variable substitution $\rho=r^2$, letting $\rho<0$, thereby allowing us to represent all points inside the hyper-ellipsoid. How small can $\rho$ get? One can imagine these confocal hyper-ellipsoids continuing to shrink inwards until the short axis shrinks to 0: assuming $a<b$, when $\rho=-a^2$, the $x$ and $y$ coordinates shrink to a point and can’t shrink any further (otherwise $\sqrt{r^2+a^2}$ would become imaginary), and the entire surface becomes a solid disk with radius $\sqrt{b^2-a^2}$ on the $zw$ coordinate plane.

It can be proven that when the mass in the Myers-Perry black hole metric is not 0, as long as parameters $a$ and $b$ are not both 0, although the coefficients of certain metric terms diverge on the entire $r=0$ coordinate surface, the curvature is a finite value with no singularity. This confirms that extending $r^2$ to negative numbers as we just did is also correct when there is mass. However, upon extending to $\rho=-a^2$, calculations find that on the solid disk of radius $\sqrt{b^2-a^2}$, only the edge has a singularity, so it is also a ring singularity.

MP Black Hole Photos

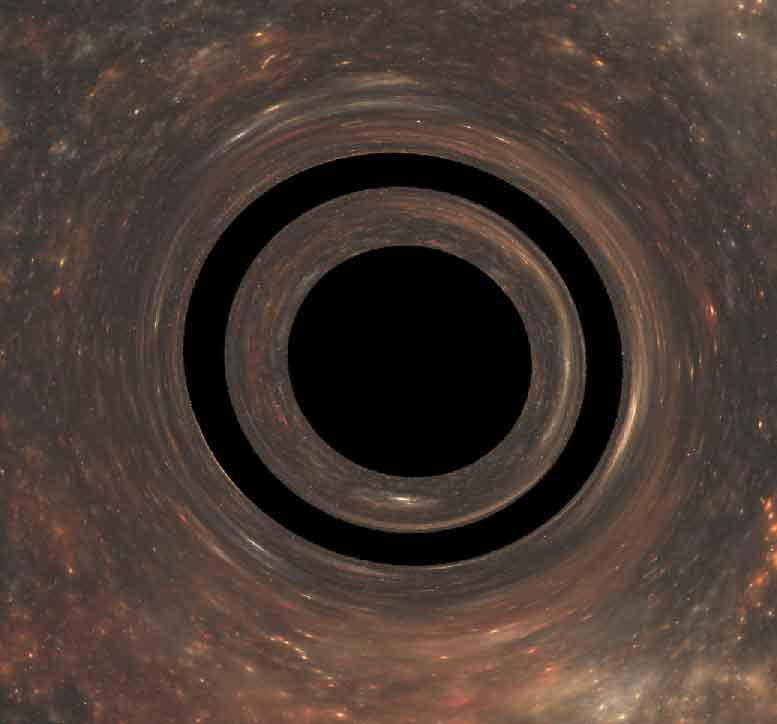

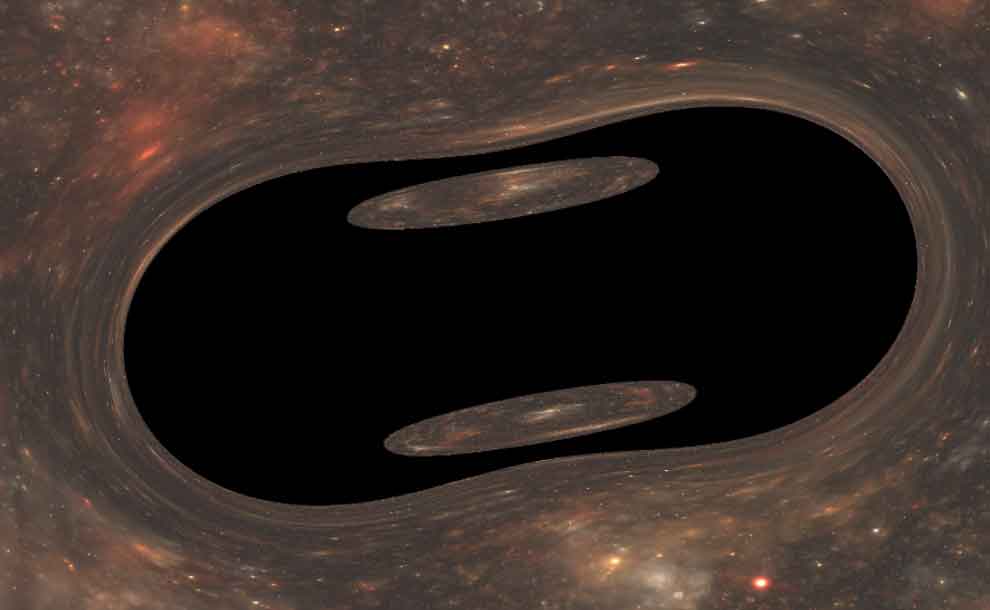

I use the Kerr-Schild coordinates, similar to Cartesian coordinates, recommended by CFY to calculate the MP black hole. However, in this coordinate system, light rays cannot enter the region where $r^2<0$ analyzed above. This causes the GPU to calculate the square root of negative numbers, exploding directly into NaN (Not a Number), which is forcibly rendered as black.

When the black hole rotation speed is small, it looks not much different from a 4D Kerr black hole: the accretion disk is wider on one side and narrower on the other, with rotation breaking the symmetry between the two sides.

You might feel the difference in width between the two sides isn’t very obvious. Actually, if I just increase the rotation speed a bit more, the black region requiring coordinate extension will rush out of the event horizon: as can be seen, a black area protrudes on the left side, and the surrounding starlight is not distorted along the boundary, indicating this part is forcefully gouged out. However, there is another difference from the Kerr black hole, which is that the disk band on the left appears broken. This is not quite the same as the Kerr situation; there are also issues here with judging whether light falls into the horizon. It might already be a naked singularity, or perhaps my calculations are incorrect.

As for the simulation of the traditional 4D Kerr black hole, I recommend this website (I suggest making the browser window smaller, otherwise there is a risk of freezing your computer).

Wormhole Structure?

I mentioned before that at $r=0$, the confocal hyper-ellipsoid can continue to shrink inward into a disk. The paper points out that this contraction can proceed further into the interior because calculations show that the curvature in most regions passed by continued extension is finite; that is, there is no singularity stopping you from passing through. However, there are some topological issues here. To explain clearly, let’s first look at how the wormhole structure of a 4D Kerr black hole works.

The connection structure of the black hole/white hole regions of a Kerr black hole is actually not obtained by letting $r^2<0$, but by selecting the other branch where $r<0$ (while still satisfying $r^2>0$). Why do scientists think passing through this ring leads to a new world? Because calculating the derivative of the axial coordinate with respect to the $r$ coordinate at the Kerr black hole reveals it is non-zero on the ring surface. According to symmetry, approaching the ring surface from above and below would generate opposite derivative gradients. If we directly consider the spaces on both sides connected, a sharp angle would form in space here. We might as well start directly from the sharp angle and extend both sides out, thus constructing the white hole region on the other side—a spacetime with negative mass, no event horizon, and a naked singularity. In the 4+1 dimensional case, things are different. We can no longer extend the space inside the circumference; this sharp angle likely cannot be eliminated. We previously analyzed the simple connectedness of space, which presents a topological obstacle regardless of the extension method used: to glue two pieces of an $n$-dimensional manifold together, the boundary of their “seam” must be $n-1$ dimensional, otherwise it is no longer a manifold at the “seam”. If this is hard to understand, think of a 2D case first: imagine a 2D planar space with polar coordinates established. It can approach the origin $r=0$ from $r>0$ and then enter a new region where $r<0$. The entire space topologically becomes something like a double cone. Calling it a cone isn’t quite accurate either: the entire plane has zero curvature, and going around the pole is still 360°, so it can be viewed as a double cone compressed to be infinitely flat, almost approaching a plane.

However, except for a point mass, no object with size can completely pass through the pole to the universe on the other side where $r<0$: actually, no object can pass, unless its fundamental particles pass through the origin with absolute precision, which is completely impossible under quantum uncertainty. Note that the curvature of the entire space, including the pole, is 0. This means that although there are no singularity obstacles like curvature divergence, there are topological obstacles in space making this extension impossible.

The examples above show that a 2D object cannot pass through a point-like portal; it requires a 1D portal with width to support the passage of a 2D object. Similarly, a 3D object cannot pass entirely through an infinitely thin line segment; the portal must have a 2D area. By the same logic, a 4D object requires a portal of at least 3 dimensions to pass through.

The paper mentions that for rotating black holes in odd-dimensional spacetime (even-dimensional space), if one rotation plane is static, a hypersphere will appear in the remaining vertical subspace. Curvature singularity exists only at the edge, but a “conical singularity” weaker than the curvature singularity exists inside the hypersphere—that is the sharp angle situation. The case we are discussing here is flat spacetime. When the mass term is added, that cone is no longer flat. Even without extension, we will find that the angle around the spacetime near the cone point is no longer 360°, and the spacetime manifold here becomes an “Orbifold” with poor properties. I mentioned before that this phenomenon also exists in traditional 4D Kerr black holes, except that the 3D space on both sides of the Kerr black hole’s singular ring disk acts like a dihedron here. As long as the faces continue to extend (i.e., extending into a wormhole), the singularity disappears. Unfortunately, this paper did not analyze the more general case at all—that is, the non-manifold nature of the extended space when angular momenta on all rotation planes are non-zero. It merely analyzed mechanically whether the curvature would diverge after coordinates take certain values. I tend to think that, just like the extension of the polar coordinate system, the Myers-Perry black hole can at most be extended to the point where $\rho=-a^2$. The 3D volume of the intermediate 2D disk region is 0, unable to continue supporting any object with 4D volume to pass completely through it into a possible wormhole. However, the metric of the MP black hole with a mass term is no longer flat space; what the spacetime structure is like here requires further analysis, and the possibility of entering the black hole cannot be ruled out. For example, another paper draws the shape of the singularity inside the black hole, but his coordinate system corresponds to forcibly tearing a hole in the origin of flat spacetime coordinates when mass is zero, and then filling it with things. Although impossible when flat, it might actually make sense in curved spacetime with mass.

I also asked CFY, who is an expert in this field. He said that theoretically, whether it can be extended depends only on whether there is an obstacle of curvature divergence, but the thing extended this way is definitely not a wormhole. He doesn’t know what it would be either. If you have different views, feel free to leave a comment for discussion.

Summary

Now we can finally describe the singularity of an arbitrary double rotation black hole with the 5D Myers-Perry metric:

- When the black hole undergoes single rotation, similar to the Kerr black hole, the singularity is a disk. Its edge has a curvature singularity, while the interior is a conical singularity. It is wrapped within inner and outer horizons, and the infinite redshift surface is tangent to the outer horizon at the axis of rotation.

- When angular momentum also begins to increase on the other absolutely perpendicular plane, the ring singularity will slowly shrink. The infinite redshift surface at the axis of rotation will also slowly detach from the outer horizon, with no point of tangency. The ring singularity cannot prop open a wormhole in 4D space. 4D organisms cannot rely on black holes for wormhole travel and must think of other more complex methods.

- In the case of isoclinic double rotation, a.k.a Clifford rotation, the ring singularity degenerates into a point singularity. None of the topological mutations mentioned earlier will occur. The entire black hole consists of three layers of hyperspheres from outside to inside: the infinite redshift surface, the outer horizon, and the inner horizon, with the singularity located at the center of the hypersphere.

High-Dimensional MP Black Hole

In high-dimensional spacetime, to prop open a wormhole inside a rotating black hole, the dimension of the singularity must be relatively large to destroy the simple connectedness of spacetime. The shape of the singularity originates from the non-uniformity of rotational speed: superficially, the singularity of the Myers-Perry metric is a hyper-ellipsoid proportional to the angular velocity at each point. However, as long as this hyper-ellipsoid can undergo “confocal contraction,” it can continue to extend inward through contraction until the length of some axes of the hyper-ellipsoid becomes 0, encountering a true curvature singularity. For instance, a non-rotating black hole and a perfectly symmetric cliford rotation black hole have the same linear velocity everywhere; their singularities are both a point. Only non-isoclinic double rotation or single rotation will tear the singularity into a ring shape. In 6D spacetime (5D space world), we can construct a double rotation black hole, but there exists an axis in the fifth dimension that does not participate in rotation. It is conceivable that the singularity of this planet is located in the 4D subspace perpendicular to that axis. Depending on whether the double rotation is isoclinic, the singularity may be a regular hypersphere or an ellipsoidal hypersphere. Excavating this hypersphere, the 5D space is no longer simply connected. We can pass through it in the direction perpendicular to the fifth dimension, and perhaps come out of a white hole to reach a new universe. Below I have listed a table summarizing the MP black hole structures for the first few dimensions. Here I tentatively assume that extending confocal circles that are simply connected in space results in conical singularities, and I have marked these uncertain cases with a question mark (it is very likely that they can continue to extend inward for some distance, but there will be no wormhole). If there are different views, please point them out:

| Rotation Type | 4D Case | 5D Case | 6D Case | 7D Case | 8D Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Rotation | S1 Curvature Singularity, Wormhole | S1 Curvature Singularity, D2 Conical Singularity, No Wormhole | D2 Curvature Singularity, No Wormhole | D2 Curvature Singularity, No Wormhole | D2 Curvature Singularity, No Wormhole |

| Double Rotation | - | S1 Curvature Singularity, D2 Conical Singularity? No Wormhole | S3 Curvature Singularity, Wormhole | S3 Curvature Singularity, D4 Conical Singularity, No Wormhole | D4 Curvature Singularity, No Wormhole |

| Isoclinic Double Rotation | - | Point Singularity, No Wormhole | S3 Curvature Singularity, Wormhole | S3 Curvature Singularity, D4 Conical Singularity, No Wormhole | D4 Curvature Singularity, No Wormhole |

| Triple Rotation | - | - | - | S3 Curvature Singularity, D4 Conical Singularity? No Wormhole | S5 Curvature Singularity, Wormhole |

| Triple Rotation/$a=b<c$ | - | - | - | D2 Curvature Singularity, No Wormhole | S5 Curvature Singularity, Wormhole |

| Triple Rotation/$a=b>c$ | - | - | - | S3 Curvature Singularity, D4 Conical Singularity? No Wormhole | S5 Curvature Singularity, Wormhole |

| Isoclinic Triple Rotation | - | - | - | Point Singularity, No Wormhole | S5 Curvature Singularity, Wormhole |

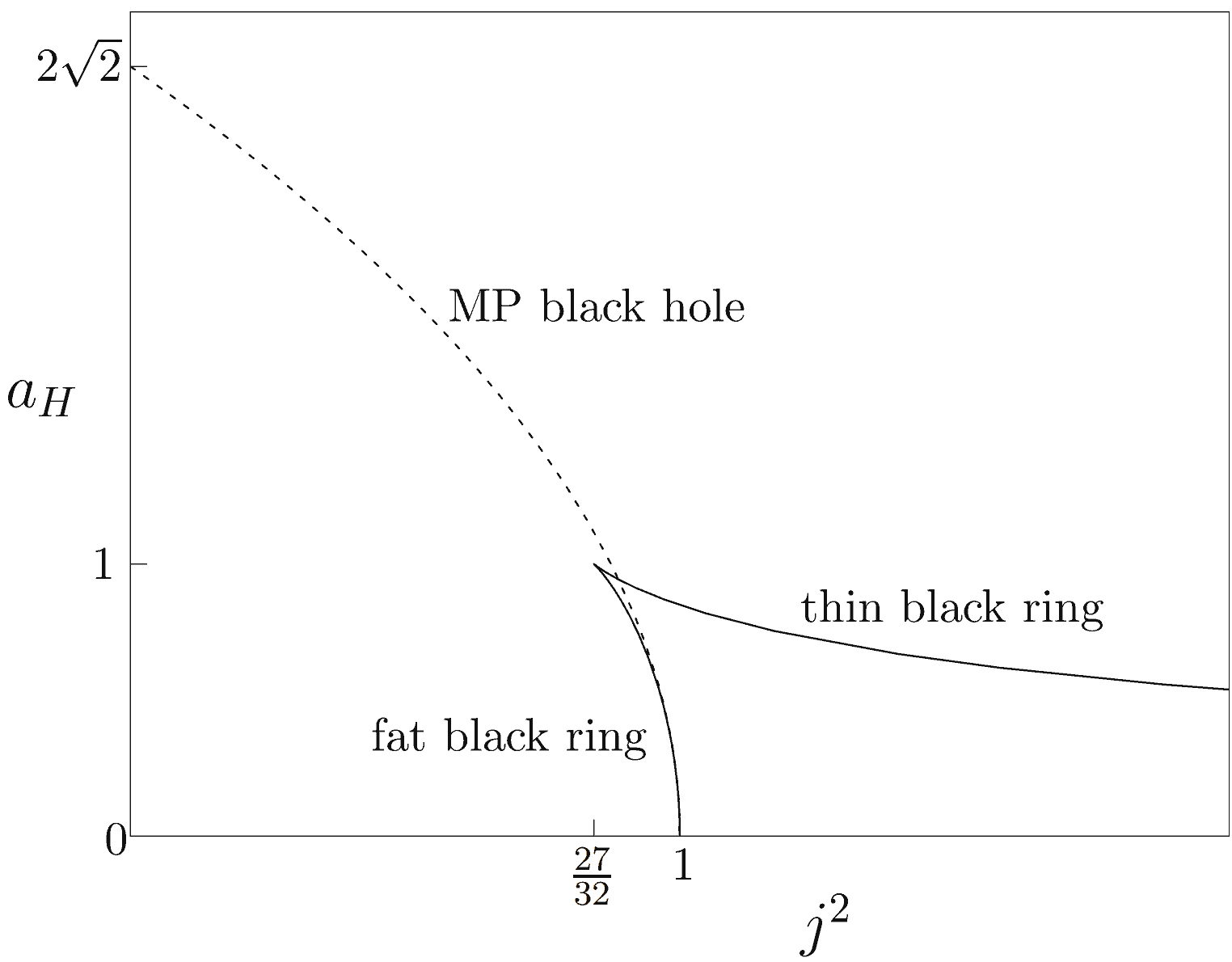

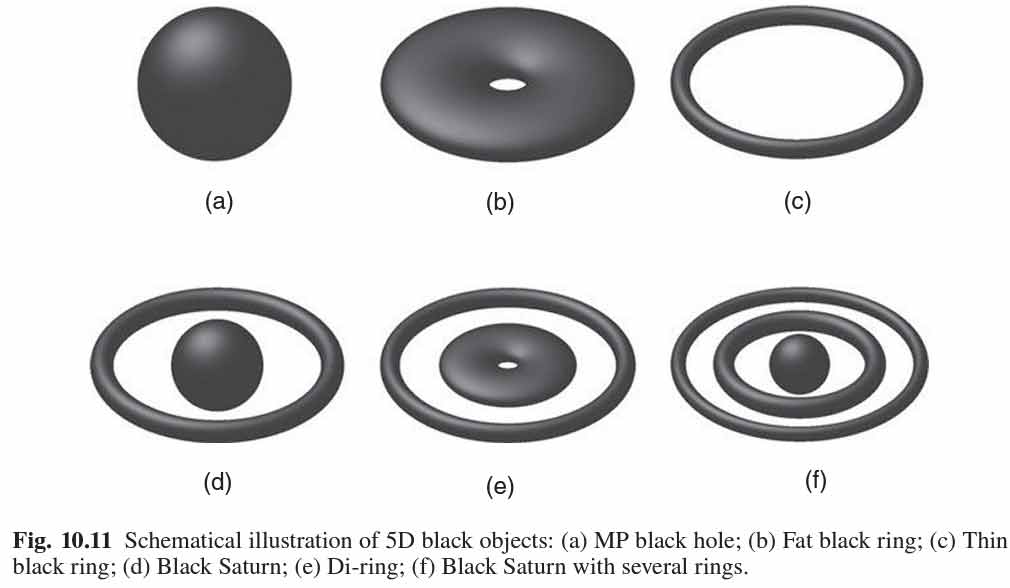

New One: Black Ring

By researching solutions to Einstein’s equations, one can discover that in 5D spacetime there exists a black hole solution different from the Myers-Perry metric, called the “Black Ring”. Its horizon is the surface of a spheritorus ($\mathbb{S}^1\times\mathbb{S}^2$). Since the shape of the black ring is empty in the middle, it will spontaneously collapse under gravity. To make the black ring stable, it must rotate, maintaining balance under centrifugal force. Therefore, there is a constraint relationship between the black ring’s angular momentum, mass, radius, and thickness parameters. It is worth mentioning that under certain conditions, a black ring can have the same parameters as the MP black hole introduced earlier. This means we have found a counterexample to the no-hair theorem: the no-hair theorem only holds in four-dimensional spacetime; it fails in five dimensions and higher!

Understanding the metric expression of a black ring is even harder. Below I will just roughly list some conclusions:

- The topological structure of the black ring’s horizon is a spheritorus, while the MP black hole’s horizon topology is a hypersphere (note that a hyper-ellipsoid and a regular hypersphere are topologically the same).

- The structure of a black ring is actually similar to a “Black String” obtained by directly cylindrically extending a Schwarzschild black hole from 4D spacetime (our universe) along the fifth dimension, and then bending the black string into a ring.

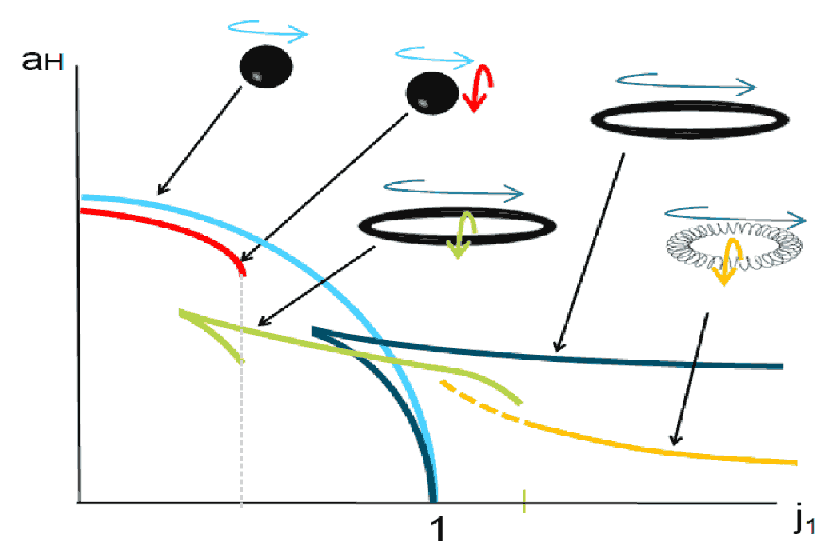

- Under the same parameters, besides potential MP black hole solutions, the black ring itself may have two sets of solutions: one called the thin black ring, and one called the fat black ring. As shown in the figure below, when the angular momentum parameter $j^2$ is between ${27\over 32}$ and $1$, there are a total of three solutions.

- Black rings can also have double rotation solutions: one direction is around $\mathbb{S}^1$, and the other is an absolutely perpendicular rotation direction within $\mathbb{S}^2$. You might intuitively think of the non-rigid rotation of a smoke ring turning inside out, but the double rotation of a spheritorus is completely rigid and does not turn inside out like a smoke ring. In addition, there exists a Helical Black Ring, which requires double rotation to exist stably.

- The black holes mentioned above all possess a single horizon. If multiple horizons are allowed, there also exist structures like “Black Saturn” (figure (d) below) consisting of a black hole plus a black ring, as well as more complex nested structures like multi-layered black rings.

- For higher-dimensional black holes, their stability might “bifurcate” as the angular momentum parameter increases, transforming into more complex shapes. This is somewhat similar to the stability of the shapes of rotating planets.

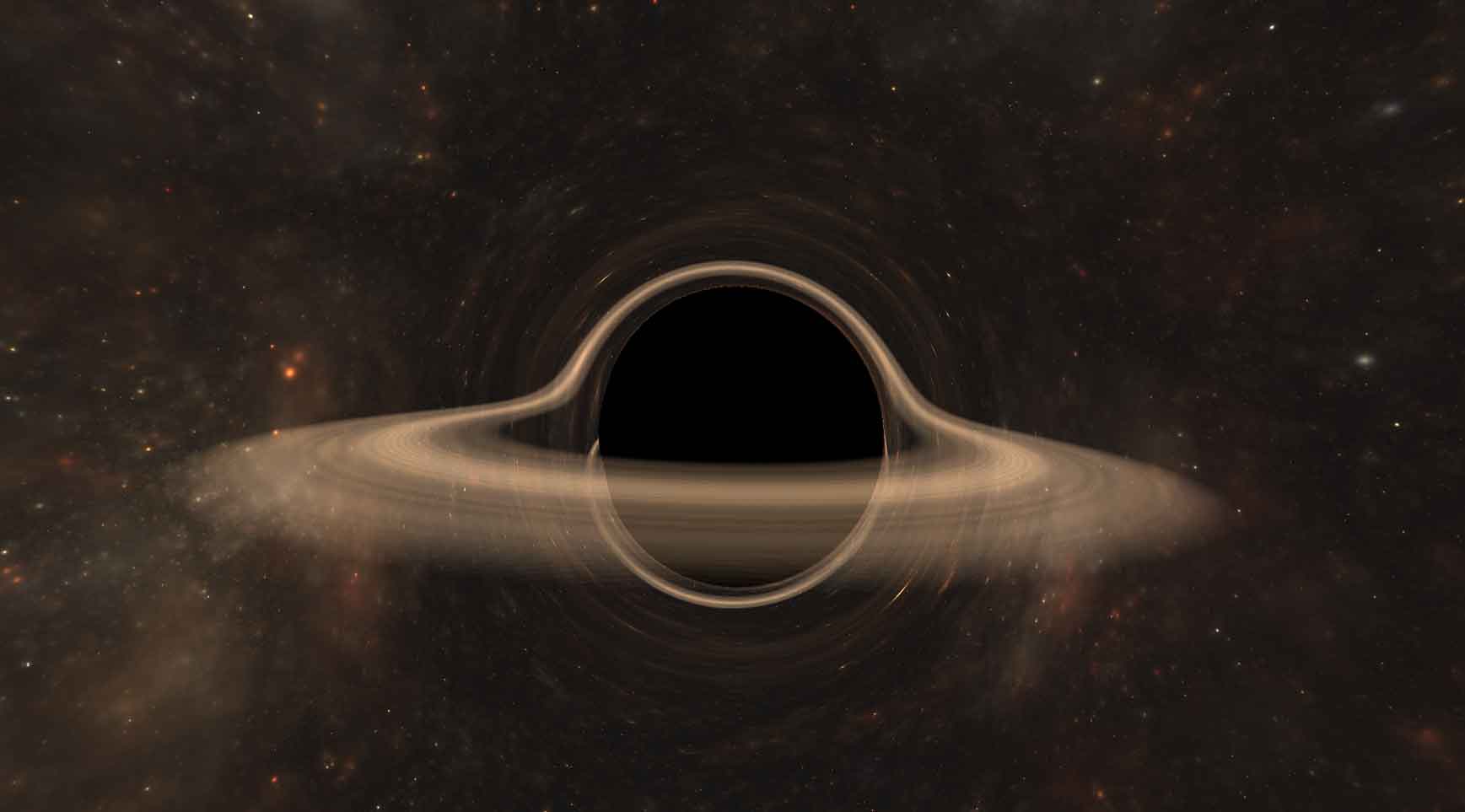

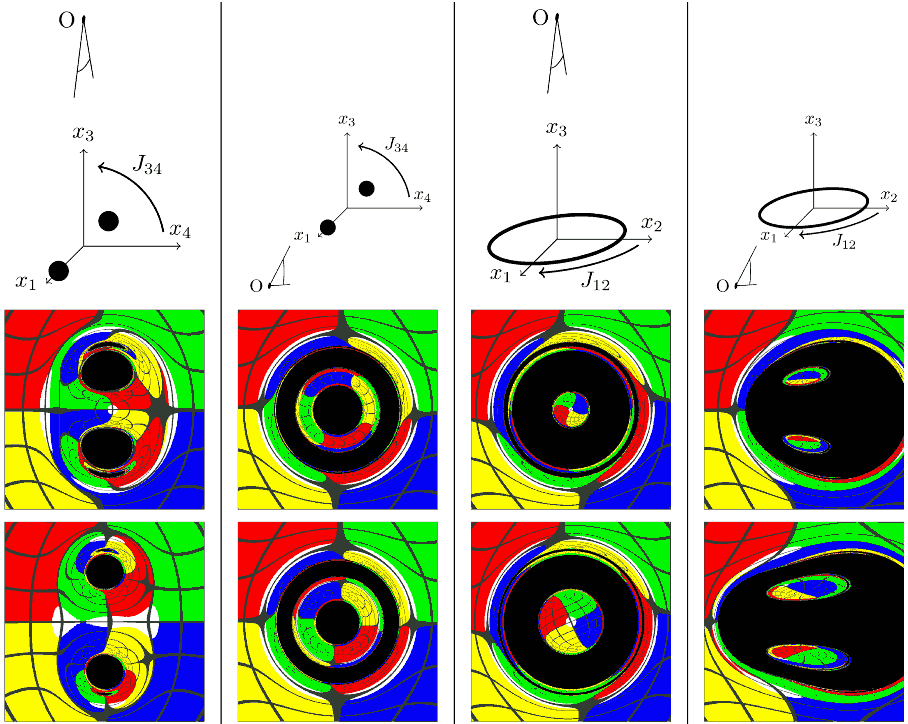

Visualise Black Rings

Visualization of MP black holes and black rings has been studied before. I found a paper where the authors extracted two typical cross-sections of a spheritorus: one consisting of two spheres, and the other a ring (torus). The authors point out that if you look at the rendered cross-section of the black ring that cuts out two spheres, you will find it looks very similar to spacetime containing two black holes in traditional 4D spacetime. For example, if viewed from the line of sight where one black hole is directly behind the other, its black hole shadow will be distorted into a ring shape. When viewed perpendicular to the line connecting the two black holes, since light can orbit around both black holes, it results in distorted images of the other black hole’s shadow appearing on the sides of the black holes, resembling eyebrows.

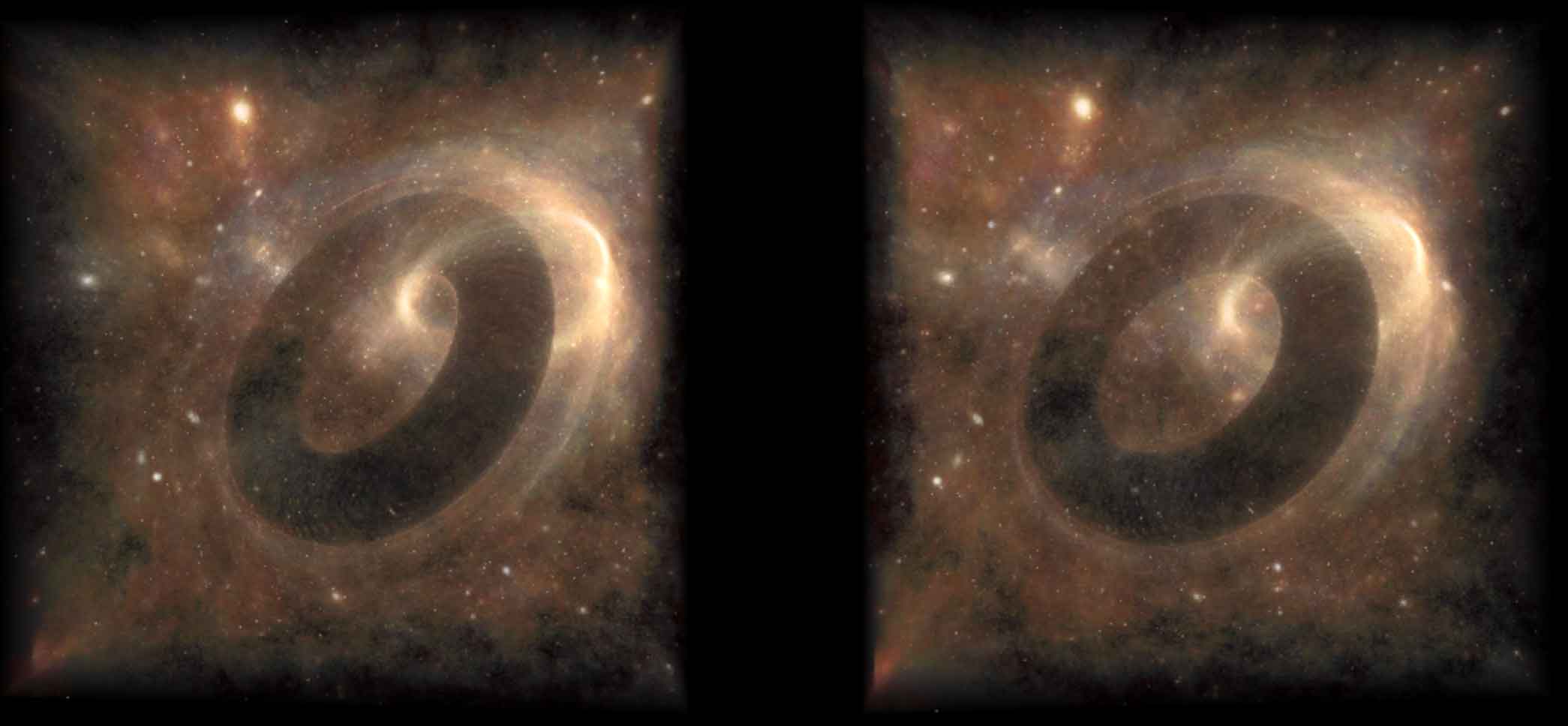

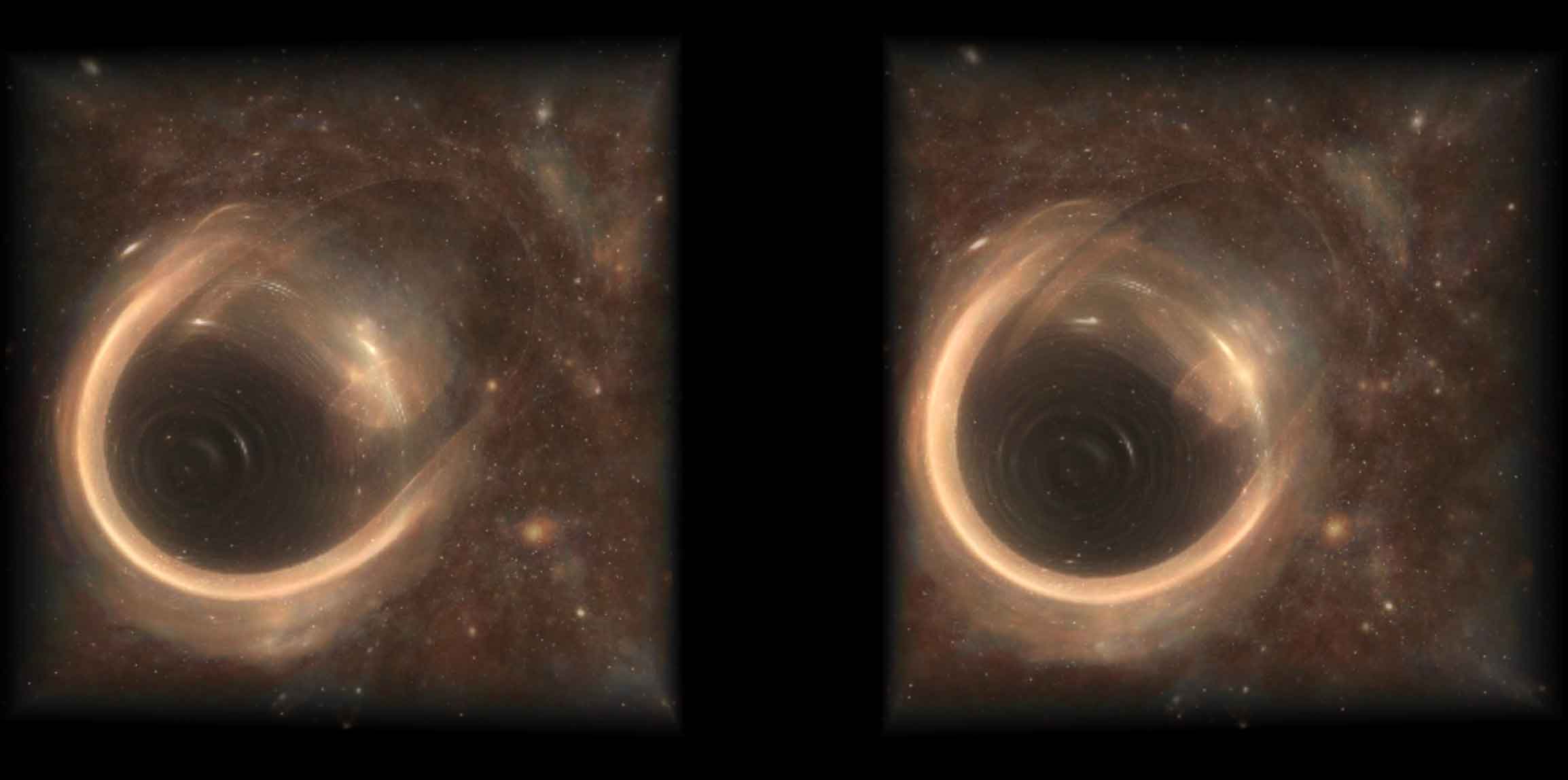

The metric expression for the black ring is too complex, so I gave up on calculating it myself. However, the Schwarzschild black hole’s equivalent potential from before reminded me that perhaps I could build an electric field potential model of a charged ring to directly distort light, to see if I could obtain images similar to those in the paper above. The result was that the images I got looked really similar to the black rings in the paper! Except for one point: light in the two directions of the black ring’s rotation should theoretically have asymmetry like a Kerr black hole, causing one side of the black ring to be thick and the other thin. My charged ring could only simulate static attraction and could not simulate the frame-dragging effect caused by rotation, so both ends were of equal thickness. I tried adding a magnetic field term to the model, treating photons as charged particles and adding the contribution of deflection by Lorentz force in the magnetic field. I found that neither the Kerr black hole nor the black ring looked anything like the real situation, so I had to give up on adding rotation. However, these static “pseudo-black rings” still look quite beautiful. (Note: I did not add any accretion disk around the black ring, link here, click on Black Ring in the top right corner).

Below are some voxel cross-section photos from specific angles; you can see that they indeed look very similar to the black ring images in the paper:

You may wonder what these cross-sectional shapes look like throughout the voxel. The answer is the solid of rotation of the figure in the fourth column of the paper’s illustration:

In addition, I also captured a similar interesting black object with a classic double-circle cross-section of a ring:

Black Ring as the Sun?

Finally, one point I want to mention separately is that people have already demonstrated that stable planetary orbits do not exist around MP rotating black holes, while the Black Ring might be the candidate for the “Sun” of a planet where a 4D civilization resides. This is because this paper points out that it is possible for stable orbits to exist around a Black Ring. I understand it this way: tentatively ignoring the relativity part, from a distance, the Black Ring is just an ordinary 4D star; planets either fall in or escape. But when a planet gets close and “zooms in”, the falling planet does not crash directly into it, but passes through the hole in the middle; viewed from up close, the field around the linear mass of the Black Ring is equivalent to the field around a point mass in ordinary 3D space obtained by approximate “Extrusion” to new dimension. It is not surprising that there are stable orbits. Here I also performed a non-relativistic simulation of planetary orbits around a ring-shaped celestial body in Tesserxel (using an RK4 integrator), and found that there are indeed stable orbits! If the sun were ring-shaped, the dates, calendars, and seasons on the planets introduced earlier would all change. However, the planet would be on the outside of the solar ring for a while and then drill into the inside of the solar ring. The temperature variation span might be very large, and it could be a difficult matter for the planet’s orbit to fall completely within the galaxy’s habitable zone.

References

- arXiv:1111.1903 [gr-qc] Myers-Perry black holes Introduction to MP black hole metric and structure.

- arXiv:1711.02933 [gr-qc] Geodesic motion in the five-dimensional Myers-Perry-AdS spacetime Mainly discusses MP black holes in negative constant curvature spacetime, drawing the singularity of MP black holes extended inward to .

- arXiv:1903.05125 [hep-th] Imaging Higher Dimensional Black Objects Rendered voxel cross-sections of MP black holes and Black Rings.

- arXiv:2411.02511 [gr-qc] Darkness cannot bind them: a no-bound theorem for d=5 Myers-Perry null & timelike geodesics Analyzed the stability of timelike and null orbits around spinning black holes.

- arXiv:1302.0291 [hep-th] Stable Bound Orbits of Massless Particles around a Black Ring Black Rings can have bounded timelike and null geodesics around them, i.e., stable orbits.

- arXiv:1003.2411 [hep-th] On the black hole species (by means of natural selection)