4D World (XII): Matter Structure

// This is the hardest English translation revision on this site. I have to learn all the compound naming rules in English because I only studied chemistry in Chinese.

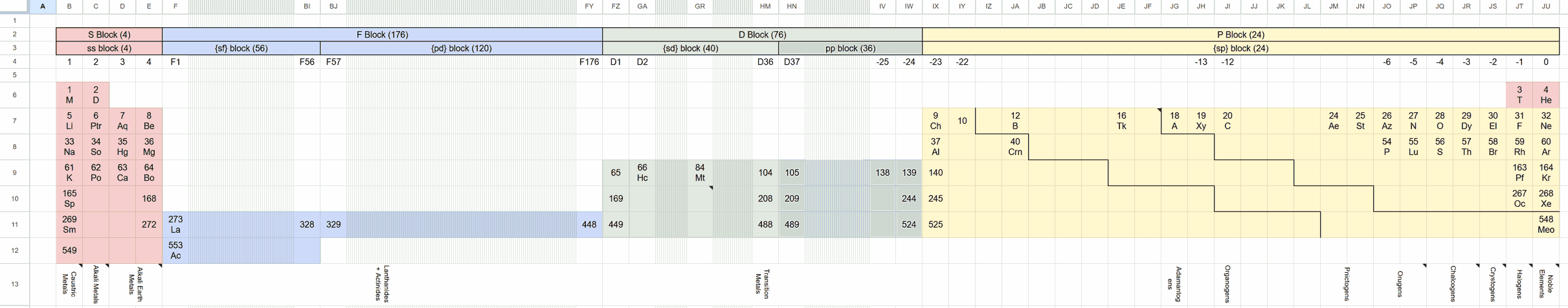

Last time we explored the 4D periodic law settings. This time let’s look at matter structures and make some bold, groundless predictions about their properties (I’m not a chemistry major, so everyone is welcome to raise objections to any content). As I was continuing to write this section, netizen KWOK Chun shared with me an online Google document called “Symmetric 4D Chemistry”, where the 4D chemistry periodic table setting is exactly the same as mine, only the element naming is different. When I was nearly finished writing this article, I also saw 4denthusiast’s Blog which specifically discusses 4D chemistry and attempts quantitative computational analysis. They try to establish a more rigorous 4D fundamental physics system starting from elementary particle physics, and I will share some wonderful content.

As I was continuing to write this section, netizen KWOK Chun shared with me an online Google document called “Symmetric 4D Chemistry”, where the 4D chemistry periodic table setting is exactly the same as mine, only the element naming is different. When I was nearly finished writing this article, I also saw 4denthusiast’s Blog which specifically discusses 4D chemistry and attempts quantitative computational analysis. They try to establish a more rigorous 4D fundamental physics system starting from elementary particle physics, and I will share some wonderful content.

Featured Content

- Electron formulas, structural formulas and bond-line formulas

- Molecular orbital theory and VSEPR model

- Acids and bases and 4D ocean biosphere setting

- Spatial isomerism and 4D molecular browser

- Hyperdiamond and 4D crystal systems

- Particle physics standard model and preliminary computational chemistry

- Other periodic law worldview settings

Representation Methods for Molecular Structures

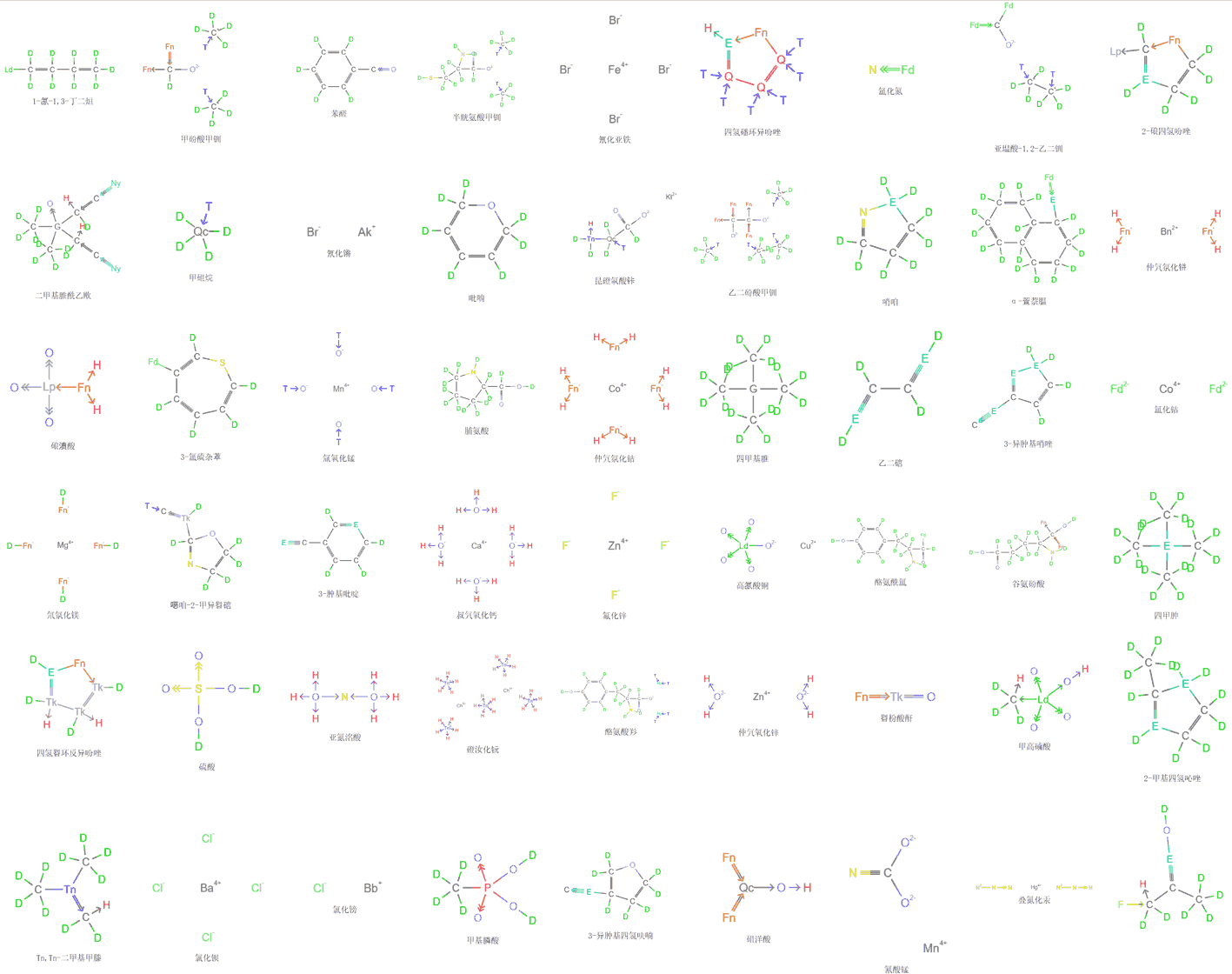

At the end of the previous article, I introduced compounds that can be formed between hydrogen-like elements (protium, deuterium, tritium) and showed electron formulas for covalent bonds where multiple atoms together contribute 4 electrons to fill orbitals. There are more elements in the second row, and the types of compounds they can form may be several orders of magnitude more than in 3D. Let’s first systematically study how to write valid molecular structure electron formulas, then list some possible molecular structures.

Electron Formulas

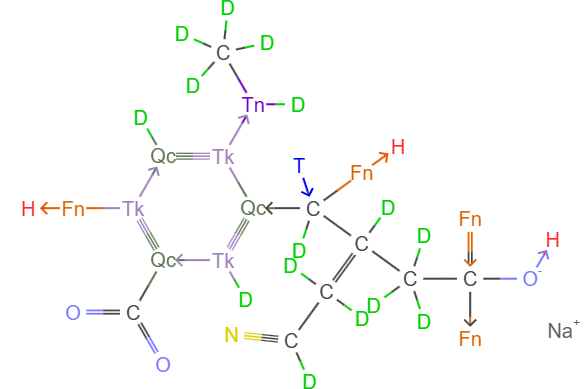

When writing electron formulas, atoms need to achieve noble gas stable structures. First-row elements need to follow the four-electron rule, and second-row elements need to follow the twenty-electron rule. Below are electron formulas for some molecules formed by fluorine (F), fudine (Fd), and funigen (Fn), which are one, two, and three electrons short of twenty electrons respectively.

Structural Formulas

Writing 4D electron formulas is cumbersome, so we need more concise structural formulas. The rules for 4D structural formulas should be able to verify whether each atom achieves noble gas stable structure, and also verify whether the number of electrons in each orbital sharing electrons is 4. After continuous attempts, I designed a relatively practical structural formula representation method:

- For ions, simply mark the charge. For each orbital of covalent bonds, follow these rules:

- If an atom provides 2 electrons, use a solid line;

- If an atom provides 1 electron, use an arrow pointing toward that atom; if it provides 3 electrons, use an arrow pointing away from that atom;

- If an atom provides 4 or 0 electrons (coordinate bond), use a double arrow pointing away from or toward that atom. Alternatively, draw lines according to the previous two cases and record the undercounted electrons by marking excess formal charges.

- An orbital can be shared by multiple atoms, which may contribute different numbers of electrons, and the branching line types can also be different. Use a solid dot at the branch point to represent the orbital. If only two atoms share the orbital, there’s no branch, the dot can be omitted, and the arrow can be drawn through.

Below are the structural formula versions corresponding to the electron formulas of the molecules shown earlier: these arrows nicely indicate the source of bonding electrons.

After I completed the structural formula setting, I found that “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” had already proposed similar structural formula notation, with just some symbol differences: when both sides provide 2 atoms each, it’s called a nondative bond, still represented by a line; when each provides 1 and 3 electrons, it’s called a semidative bond, with a vertical line drawn on the side providing three electrons; Dative bonds are represented by normal single arrows. Some element Chinese names in “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” use the same Chinese characters I also used, but correspoding to different elements. Below are some examples: the left side is my notation (default in this article), the right side is the notation for the same substances in “Symmetric 4D Chemistry”.

Stable Structure Determination

How do we determine if a structural formula meets both requirements of noble gas stable structure and 4 electrons per orbital? Below are the structural formula verification rules:

- First introduce the concept of bond number. Each atom or orbital has a bond number, calculated as: normal solid lines count as single ($1$) bonds, each arrow pointing toward oneself adds an extra $0.5$ bonds, arrows pointing away subtract $0.5$ bonds;

- For atoms that are $k$ electrons short of noble gas structure, their total bonding number should be $(k+e)/2$, where $e$ is the formal charge marked on that atom, and the total charge of the entire molecule should be $0$;

- For each shared orbital, calculate its bond number which should always be $2$.

- Due to orbital number limitations, first-period elements can have at most one line connected to them, and second-period elements can have at most $5$ lines connected to them.

From the second rule we can deduce that under normal uncharged conditions, protium (H) needs to form 1.5 bonds, deuterium (D) forms 1 bond, tritium (T) forms 0.5 bonds; fluorine (F) forms 0.5 bonds, fudine (Fd) forms 1 bond, funigen (Fn) forms 1.5 bonds. Everyone can verify the bond numbers of atoms in the figures above themselves.

Finally, a small corollary: generally speaking, in an electrically neutral molecule, the number of atoms with odd atomic numbers must be even. Of course, there are exceptions, such as molecules like nitric oxide in the three-dimensional world that have unpaired electrons showing paramagnetism. These phenomena require molecular orbital theory to explain. Here I declare again that the content of this article, including molecular orbital theory, is completely baseless analogy. The stability conclusions of “actual” 4D matter may be very different. Later we will introduce possible 4D particle physics and attempts at 4D computational chemistry.

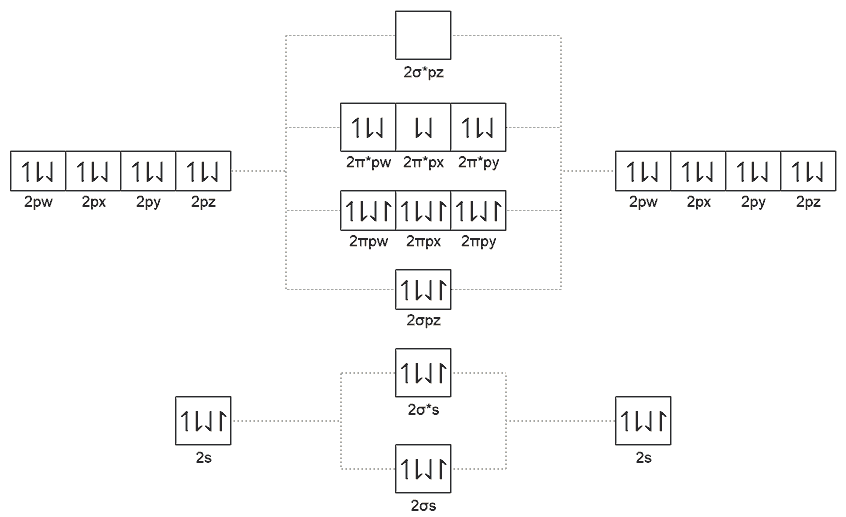

Optional Reading: Molecular Orbital Theory [Expand/Collapse]

Multi-center Bonds and Electron-rich Compounds

Multi-center bonds are bonds formed by multiple atoms sharing electrons, which can explain electron-deficient molecules such as diborane and boron trichloride. The protium gas molecule H4 in the 4D world is a typical electron-deficient molecule. In the thinking question left in the previous article, I mentioned what the elemental form of tritium would be. Tritium has 3 electrons and lacks one electron, so it can only form electron-rich molecules: four tritiums can share 12 electrons to form three filled bonding orbitals. Some netizens also proposed that it could actually form diatomic molecules directly - they only need to share one electron each, so each atom would have four electrons. Is such a structure valid? Molecular orbital theory believes that the essence of bonds is not just sharing electrons. Generally, two atomic orbitals recombine to form two molecular orbitals, one with high energy (antibonding orbital) and one with low energy (bonding orbital). Electrons all fill the low-energy orbital, leaving the high-energy orbital empty. This makes the overall energy lower than two separate atomic orbitals each with one electron, hence more stable. Four tritium atoms have four atomic orbitals, and their linear combination still results in four molecular orbitals, similar to changing coordinate basis in linear space while maintaining dimension. They share orbitals, not electrons. Electrons can only fill orbitals. In diatomic tritium molecules, it’s impossible to share only 2 electrons while keeping the rest private, because orbitals either overlap to form bonds or don’t bond at all.

Electron-rich Fluorides

How do sulfur hexafluoride and xenon difluoride analogize to 4D? First, we need to understand how these molecules exist in 3D. Sulfur originally has 6 outer electrons, lacking 2 electrons, while fluorine has 7 electrons, lacking 1 electron, so the simplest compound should be sulfur difluoride F-S-F. At this point, the sulfur atom still has two lone electron pairs. Due to fluorine atoms being highly reactive, fluorine gas can continue to react with sulfur difluoride: two fluorines each contribute one electron, a lone electron pair on sulfur contributes two more electrons, shared by three atoms, forming another 3-center 4-electron bond, resulting in sulfur tetrafluoride. Fluorine atoms originally lack only one electron, and forming a 3-center 4-electron bond makes the number of electrons outside fluorine exceed 8, hence called electron-rich molecules. But why are they stable? This can be explained using resonance structures with formal charges: in the sulfur tetrafluoride molecule below, although one fluorine appears to be ionic and different from the other three, actually different positions can alternately become negative ions. Sulfur hexafluoride has one more pair of 3-center 4-electron bonds than sulfur tetrafluoride, with a similar situation. Actual measurements of sulfur hexafluoride show all S-F bonds are equal length, indicating that the multi-center bond description is the actual situation, which can be viewed as a quantum superposition state of these resonance structures forming multi-center bonds. Resonance structures allow all atoms to conform to the 8-electron stable structure and also count the number of lone electron pairs on the central atom, thus predicting molecular spatial shape according to VSEPR theory.

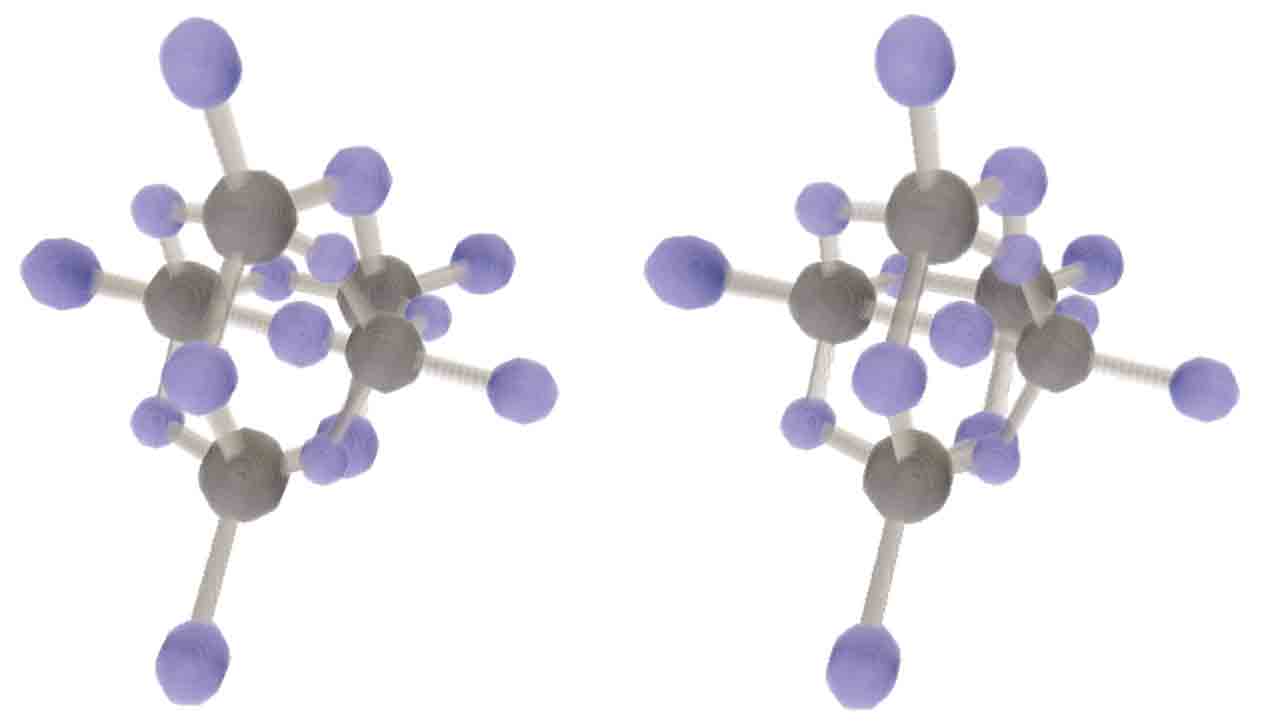

Now for 4D, here I directly give several interesting electron-rich molecules: sulfur octafudide and halcyon octatritide (analogs of sulfur hexafluoride, both are regular 16-cell molecules), nitrogen hexatritide (regular octahedral flat cell structure with two lone electron orbitals on both sides of the normal), carbon hexatritide (one lone electron orbital, causing the molecule to have a 4,3-duopyramidal shape minus one vertex on the triangle), iodine nonadecafluoride (analog of iodine heptafluoride). The figure below shows two relatively complex molecular structures, please deduce the resonance structures of other molecules not shown. Hints: 1. We’ll soon introduce 4D VSEPR theory to predict specific molecular shapes; 2. The molecules above can be found in the Chem4D molecular library, see here for specific operations.

Paramagnetism

In the real three-dimensional world, oxygen molecules are not double-bonded but triple-bonded structures. This comes from molecular orbital theory calculations, and there are unpaired electrons in the triple bond. The magnetic moment they produce cannot be canceled, causing liquid oxygen to be attracted by magnets - this is paramagnetism. “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” also drew molecular orbital energy level diagrams for oxygen molecules but didn’t give specific conclusions. My predicted conclusion is that from 3.5-valent tenaron to 1.5-valent funigen, if they can form diatomic molecules, they might all have quadruple bond structures with unpaired electrons. Fully filled orbitals must have four different magnetic moments with zero total magnetic moment due to Pauli exclusion principle. Only unpaired electrons can possibly be magnetized to maintain consistent orientation in an external magnetic field direction, so 4D oxygen molecules also have paramagnetism. Excluding that tenaron might be a solid crystal and funigen gas is a tetratomic molecule, only nitrogen gas, nyxogen gas, and oxygen gas are quadruple-bonded structures with paramagnetism. Additionally, I guess there might also be paramagnetic compounds like nitric oxide (NO) and funic oxide (FnO).

Note: Magnetism can be divided into three categories: paramagnetism, diamagnetism (or antimagnetism), and ferromagnetism. Paramagnetic materials are not strongly magnetic and cannot spontaneously form uniformly oriented magnetic domains because they would be disrupted by thermal Brownian motion. Ferromagnetism is when paramagnetism is very strong, strong enough to form stable magnetic domains. Materials without paramagnetism are diamagnetic - they hardly respond to magnetic fields. Iron is a transition metal with complex d-orbital electron energy situations, allowing stable structures with unpaired electrons that make ferromagnetism possible. The same applies to 4D chemistry, but we cannot know specifically which materials have strong magnetism.

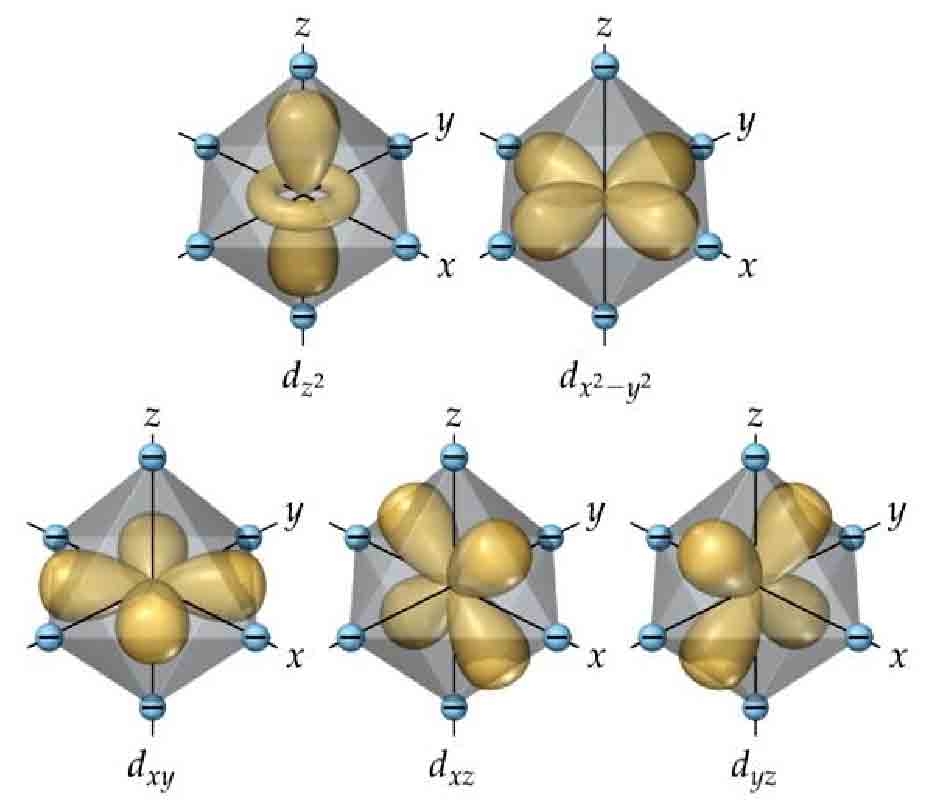

Transition Metal Ions and Crystal Field Theory

The valence states of three-dimensional transition metal ions differ from simple atoms. Usually ions are surrounded by many ligands, for example copper ions exist in solution as hydrated ions. Crystal field theory believes that these surrounding ligating atoms affect the energy levels of various d orbitals. For example, in an octahedral coordination field, the originally equal-energy 5 d orbitals split into two different energy levels: three low-energy orbitals and two high-energy orbitals. If the energy difference exceeds the energy required to overcome inconsistent spin directions, ions might preferentially fill the three lowest-energy orbitals before filling the remaining two orbitals. So besides the stable 0, 5, 10 electrons under Hund’s rule, 3, 6, 8 electrons are also stable. The situation with transition metal ions is quite complex, including Jahn-Teller effect, tetrahedral coordination, square planar coordination, etc., resulting in very rich valence states for the same metal ion. Without quantitative computational analysis, it’s impossible to simply determine common oxidation states of ions through rules.

The situation with transition metal ions is quite complex, including Jahn-Teller effect, tetrahedral coordination, square planar coordination, etc., resulting in very rich valence states for the same metal ion. Without quantitative computational analysis, it’s impossible to simply determine common oxidation states of ions through rules.

The 4D analog of the most common octahedral coordination field - the regular 16-cell coordination field - has d orbital energy level splitting into a 6+3 structure: 3 orbitals with low energy and 6 orbitals with high energy. In 4D space there are two cases with Hopf basis and polar coordinate basis, and the conclusions are the same for both bases:

- Under the hyperspherical orbital basis, the $xy$, $xz$, $xw$, $zw$, $yw$ orbitals are similar to three-dimensional ones, with orbital “petals” pointing between axes, not coinciding with axes; $x^2+y^2+z^2-3w^2$ and $x^2+y^2-2z^2$ head-on collide with ions on the $z$ and $w$ axes respectively, while $x^2-y^2$ collides with ions on the $x$ and $y$ axes, so these three orbitals have higher energy.

- Under the Hopf basis, there are also six orbitals $xy$, $xz$, $xw$, $zw$, $yw$ that don’t coincide with axes, which are the same; $x^2-y^2$ collides with ions on $x$ and $y$ axes, $z^2-w^2$ collides with ions on $z$ and $w$ axes, $x^2+y^2-z^2-w^2$ has maximum density in xy plane and zw plane, simultaneously colliding with all ions of the regular 16-cell, so these three orbitals have higher energy.

According to Hund’s rule, d orbital electron numbers 0, 9, 18, 27, 36 are fully or half-filled stable structures. After energy level splitting, these d orbital electron numbers are also stable: 6, 12, 18, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36. Therefore, 4D transition metals might also have multiple valence states like three-dimensional ones, but specific stability requires quantitative calculation to know.

With structural formulas, we can conveniently and quickly describe molecular structures. However, don’t forget that molecules are in 4D space, not on two-dimensional or three-dimensional paper. Let’s study their spatial structures.

Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) Model

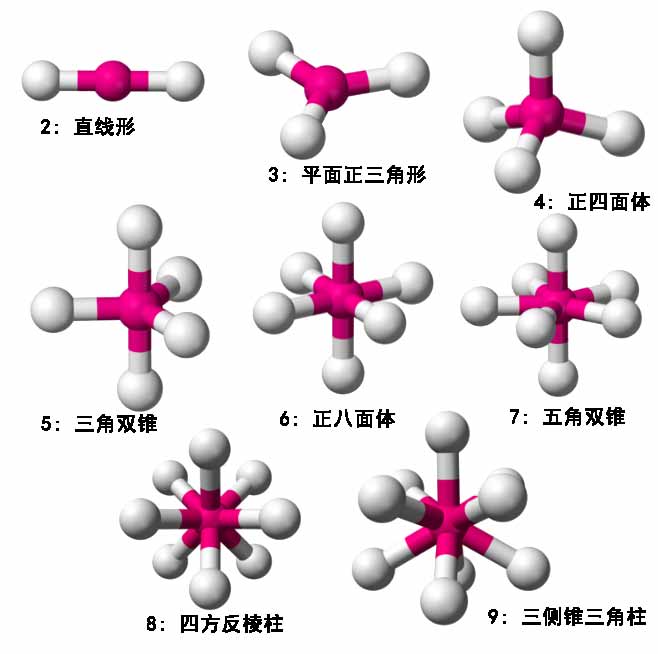

The valence shell electron pair repulsion theory believes that the geometric structure of molecules or ions is mainly determined by the repulsion between valence electron pairs related to the central atom, causing electron pairs to spread out as much as possible to minimize energy. Electron pairs can be either bonding or non-bonding lone pairs. In three-dimensional space, the geometric shapes corresponding to different numbers of electron pairs are shown below:

Let me explain the square antiprism: logically, 8 electron pairs should be most symmetrically arranged at the eight vertices of a cube. However, rotating the bottom face of the cube 45 degrees to offset it from the top face obviously lowers the energy further, hence this mode is adopted. The tricapped triangular prism (a.k.a. triaugmented triangular prism) is quite complex, see Wikipedia’s introduction.

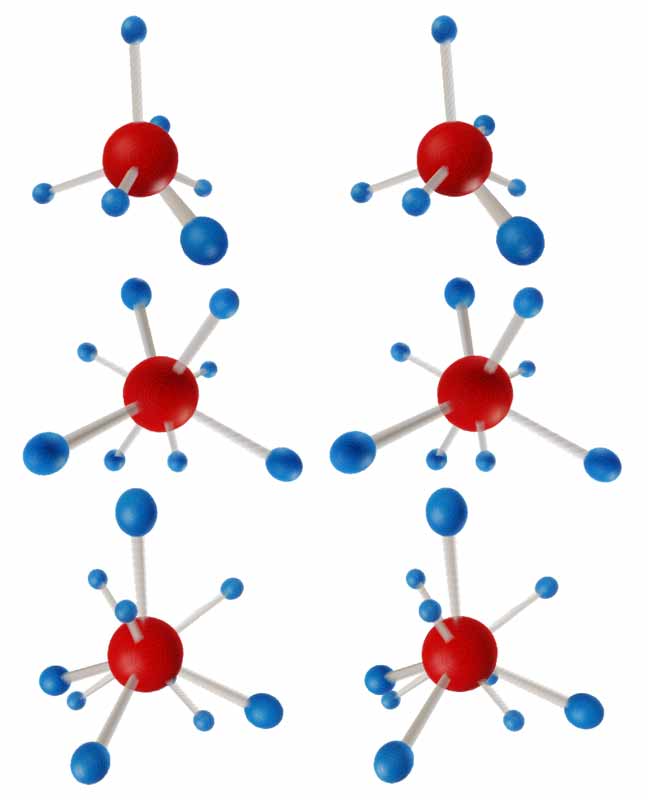

What about the situation in 4D space? “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” also gave preliminary guesses. In my VSEPR “simulation” test built on the Tesserxel platform, I observed:

- With 2-4 electron pairs (actually groups of four electrons, but we still habitually call them “pairs”), they’re actually the same as in three-dimensional space. Only when increasing to 5 electron pairs are electrons pushed into the fourth dimension, forming a regular 5-cell distribution;

- For the 6-vertex figure, both “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” and I initially thought it would be 3,3-duopyramidal, but simulation found it’s actually tetrahedral duopyramidal like trigonal duopyramidal; 7 vertices correspond to 3,4-duopyramidal (can also be seen as trigonal duopyramidal duopyramidal), 8 vertices correspond to 4,4-duopyramidal (i.e., regular 16-cell, or octahedral duopyramidal), 9 vertices correspond to 4,5-duopyramidal (pentagonal duopyramidal duopyramidal);

- After the 10th vertex, the molecular shape is neither 5,5-duopyramidal nor the structure I previously imagined similar to 4D “icosahedral” crystal system, but a layered structure - first layer has 4 vertices of a regular tetrahedron, second layer is the central atom, third layer has six vertices at positions corresponding to the edges of the first layer tetrahedron forming a regular octahedron;

- For the 11-vertex figure, I couldn’t see any clear pattern, vaguely feeling it could be divided into first layer trigonal duopyramid, second layer central atom, third layer deformed triangular prism structure; the 12-vertex figure is a twisted octahedral column similar to an antiprism, and beyond that it becomes almost impossible to see specific shape patterns.

Note: In this “simulation” program, repulsion energy is calculated according to the “real” inverse cube force decay and inverse square potential energy decay laws of the 4D world. If calculated according to three-dimensional inverse square force decay and inverse potential energy decay, the lowest energy shapes of some molecules might be different.

Having discussed a lot of theory, let’s now look at specific 4D molecules.

Common Inorganic Compounds

Non-metal Hydrides

In our world, common compounds of hydrogen with second-period non-metals are only hydrogen fluoride, water, ammonia, and methane: (Borane is an electron-deficient molecule that can only be explained using multi-center bonds, it’s uncommon so we’ll temporarily ignore it)

| Formula | Name | $e^{-}$ Pairs | Hydrogen Bonds | State | Polarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | Hydrogen fluoride | 3 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| H2O | Water | 2 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| NH3 | Ammonia | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| CH4 | Methane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Nonpolar |

In the 4D world, there are 3 types of hydrogen, and common second-period non-metal elements have also tripled, resulting in many more combinations. Below I’ve listed some representative compounds. The naming is a rule I made up: compounds with 1 to 5 shared orbitals are called “x-ide”, “x-water”, “x-ammonia”, “x-shania

I suspect compounds containing protenyl (-H2) are all very strong acids, as they easily ionize to release hydrogen ions becoming -H- and H+. In the three-dimensional world (thanks to netizen Ningning for the reminder), methane can gain a proton in super-acidic environments to become the methonium ion (CH5+) containing a three-center two-electron bond.

I just selected some representative compounds. How many combinations are there in total? I’ve listed 69 types of monoatomic hydrides from carbon to fluorine. Since we don’t know the chemical stability of “real” 4D substances, we can only assume all molecules conforming to noble gas structures are stable, and atoms with high electronegativity also form some electron-rich compounds explained by molecular orbital theory with hydrogen: such as linear deuterium fluoride, ditritium monofudide, planar triangular tritium fluoride, and planar square oxygen tetratritide. Similar to ethane and propane, those diatomic and polyatomic hydrides will be discussed later in the organic section.

| Chemical Formula | Name | Lone Electron Orbitals | Hydrogen Bonds | Room Temperature/Pressure | Polarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | Protium fluoride | 4 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| DF2 | Deuterium fluoride | 10(electron-rich) | 0 | Gas | Nonpolar |

| TF3 | Tritium fluoride | 15(electron-rich) | 0 | Gas | Nonpolar |

| H2Fd | Fudiwater | 3 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| DFd | Deuterium fudide | 4 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| T2Fd | Ditritium monofudide | 4(electron-rich) | 2 | Liquid | Nonpolar |

| H3Fn | Funiammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| HDFn | Funiwater | 3 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| DFn2 | Deuterium funide | 7 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| TFn | Tritium funide | 4 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| H4O | Oxoshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| H2DO | Oxoammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| D2O | Water | 3 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| HTO | Tritiowater | 3 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| T4O | Oxygen tetratritide | 3(electron-rich) | 3 | Liquid | Nonpolar |

| H5Ny | Nyxane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Nonpolar |

| H3DNy | Nyxoshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| HD2Ny | Nyxoammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| H2TNy | Tritionyxoammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| DTNy | Nyxowater | 3 | 2 | Liquid | Polar |

| NH6 | Protenylnitrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| NH4D | Nitrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| NH2D2 | Nitroshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| ND3 | Ammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid/Gas | Polar |

| NH3T | Tritionitroshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| NHDT | Tritioammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid/Gas | Polar |

| NT2 | Nitrowater | 3 | 2 | Liquid/Gas | Polar |

| TnH7 | Diprotenyltenarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TnH5D | Monoprotenyltenarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TnH3D2 | Tenarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TnHD3 | Tenaroshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| TnH4T | Tritiotenarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TnH2DT | Tritiotenaroshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| TnD2T | Monotritiotenaroammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid/Gas | Polar |

| TnHT2 | Ditritiotenaroammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid/Gas | Polar |

| EH8 | Triprotenylentrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| EH6D | Diprotenylentrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| EH4D2 | Monoprotenylentrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| EH2D3 | Entrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| ED4 | Shania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| EH5T | Protenyltritioentrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| EH3DT | Tritioentrane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| EHD2T | Monotritioshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| EH2T2 | Ditritioshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| EDT2 | Entroammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid/Gas | Polar |

| TkH9 | Tetraprotenyltinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkH7D | Triprotenyltinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkH5D2 | Diprotenyltinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkH3D3 | Monoprotenyltinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkHD4 | Tinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkH6T | Diprotenyltritiotinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkH4DT | Monoprotenyltritiotinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkH2D2T | Monotritiotinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkD3T | Monotritiotinkaroshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| TkH3T2 | Ditritiotinkarane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| TkHDT2 | Ditritiotinkaroshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| TkT3 | Tinkarammonia | 2 | 2 | Liquid/Gas | Polar |

| CH10 | Pentaprotenylmethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Nonpolar |

| CH8D | Tetraprotenylmethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CH6D2 | Triprotenylmethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CH4D3 | Diprotenylmethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CH2D4 | Monoprotenylmethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CD5 | Methane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Nonpolar |

| CH7T | Triprotenyltritiomethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CH5DT | Diprotenyltritiomethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CH3D2T | Monoprotenyltritiomethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CHD3T | Tritiomethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CH4T2 | Protenylditritiomethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CH2DT2 | Ditritiomethane | 0 | 0 | Gas | Weakly polar |

| CD2T2 | Ditritiocarboshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

| CHT3 | Tritritiocarboshania | 1 | 1 | Gas | Polar |

You might not be very familiar with these 4D elements, so here are the second-row non-metal elements again for reference:

Possible Acids and Bases

In the three-dimensional world, inorganic acids are generally divided into non-oxyacids (hydrohalic acids) or oxyacids. In 4D, there are more candidates for hydrogen and oxygen analogs, and the types of inorganic acids might increase explosively. Since we cannot quantitatively calculate ionization ability, I can only roughly set: protium has the strongest ionization ability, deuterium is next, tritium is weakest, generally only considering acids formed by protium and deuterium, while tritium is similar to halogens and not considered for ionization; assume that besides oxygen element, the funigen and fudine elements to the right of oxygen also participate in forming acids. Why are there only oxyacids in 3D? Logically, the stronger the non-metallic property, the easier it is to attract electrons, making hydrogen easier to ionize. Both oxygen and fluorine elements can do this. However, fluorine is monovalent - after it bonds with hydrogen to form hydrofluoric acid, there’s no opportunity to bond with other groups, so there are no fluoroacids. In 4D, this restriction is broken. Below are some common structures I’ve listed and my naming for them.

Note:

- Some acids are the same, for example nitric oxocid and nitric oxacid are actually two coexisting dynamic equilibrium structures of the same substance. Similarly, although nitric acid differs from nitric oxocid, their Acid anion are the same, so there are only nitric acid salts (nitrate), not nitrate oxocid salts (may be called nitric oxote?) or nitrate oxacid salts (may be called nitric oxate?);

- The last tritiocontaining substance in the figure I don’t classify as an acid, but rather see it as the group hydrotritide (<-O<-T) replacing the hydroxyl group in halcyonic acid to get halcyonyl.

- The acidity, basicity and stability of these things are all guesses, and the “real” situation might be completely different. See the computational chemistry section later.

Basic substances are also more diverse. Water and oxoshania and other substances can lose different hydrogen ions (H+, D2+) to form various hydroxide-like ions (OH3-, OD2-, FnH2-, FnD-, FdH-, etc.), with different basicities depending on ionization difficulty. Additionally, some molecules with low electronegativity and lone electron orbitals can accept hydrogen ions and also show basicity, for example ammonia and shania can accept deuterium ions to become ammonium ions (ND42+) and Shanum ions (ED52+). For active metal hydrides, besides corresponding to three types of hydrides, there are also some groups formed after protium gas loses protium positive ions forming “protrides” (H3-, H22-), which might serve as “protium storage” materials for 4D people… The “actual” acidity and basicity of these substances is very complex and also related to solvents, i.e., depends on the types of “water” in the 4D world.

A 4D Ocean Biosphere Setting

Netizen Ningning proposed an ocean biosphere setting: the main component of 4D planet oceans is not single water (D2O), but a mixture of several “water-like” substances. Since “water-like” substances are all polar molecules, they can be mutually soluble. I preliminarily estimated density by estimating the atomic masses constituting the molecules and found that these water-like densities don’t differ much, insufficient for component concentrations to vary significantly with water depth. Initially we hypothesized that there might be various “group-based” organisms each habitually living in their respective water layers to maintain normal physiological activities, although some of them can also live in different layers simultaneously… Note that only liquid polar hydrides of similar elements can simultaneously serve as components of 4D planet oceans. Hydrides of elements with too different electronegativities have too different acidities and basicities and would neutralize to form salts. That is, those with high electronegativity like to ionize out hydrogen, while those with low electronegativity like to use lone electrons to coordinate with hydrogen ions, similar to how ammonia and hydrogen fluoride in our world react to form ammonium fluoride. Additionally, although H4O is a gas (too few effective hydrogen bonds), we can assume it has high solubility in the ocean and also exists widely in the ocean, while those weakly polar and nonpolar molecules are difficult to dissolve in the ocean and escape to the atmosphere. Therefore, possible ocean components are mainly a mixture of funiammonia, funiwater, oxoammonia, water, tritiowater, nyxoshania, nyxoammonia, and nyxowater. The biggest difference between these substances is their acidity and basicity, although accurately defining pH value is a bit difficult when involving multiple solvents. But different effective hydrogen bonds will make these substances have different melting/boiling points and evaporation rates. Rainfall and wind direction cause the content of various components in water resources on different lands to vary greatly. Perhaps weather forecasts in the 4D world will also report recent rainwater component ratios…

Organic Compounds

In our three-dimensional world, organic compounds specifically refer to complex compounds formed by carbon element. Carbon has exactly half the number of outer electrons as noble gas atoms and can form the most bonds. Therefore, in 4D space, element 14 with 10 outer electrons is most like carbon, so I simply named it carbon. According to the electron number doubling rule, methane in the 4D world under two-electron spin setting is CH5, corresponding to 4-electron spin setting by doubling each electron number, becoming CD5. Therefore deuterium (D) is the most common element. Let me mention the bond-line formula rules here: omit carbon atoms and deuterium atoms, then opportunistically omit protium or tritium: starting from the bond-line formula, prioritize supplementing the most deuterium, then protium, and finally tritium. For example, the molecule below I name 1-protenyl-5-tritiopentane: first don’t worry about deuterium atoms, mark the terminal protenyl group (-H2), then mark the tritium atom behind. Carbon lacks 10 electrons, after tritium (T) provides 3, each deuterium (D) contributes two electrons, three deuteriums can fill 6 at most, still lacking one which defaults to being filled by protium (H), so there’s no need to mark the protium element. Directly marking protium is also possible: after marking protium, carbon lacks 10 electrons, protium contributes one electron, adjacent carbon contributes 2 electrons, leaving three orbitals that need at most three hydrogen atoms to provide 7 electrons. It’s easy to verify that supplementing 2 deuteriums and one tritium is the scheme with the most deuterium atoms among all hydrogen supplementation schemes. However, I suggest prioritizing drawing tritium, and naming likewise.

Note: In the 4D world, other elements can also replace carbon as the backbone of organic compounds, such as tinkarobenzene, dinitrane, etc. Why can’t the backbone of organic compounds in the three-dimensional world be other elements? That’s because oxygen and fluorine can form few bonds and cannot form complex structures, while nitrogen generally has a lone electron pair, and repulsion between adjacent lone electron pairs makes N-N bonds unstable. Boron is an electron-deficient molecule that can only share a bunch of bonding electrons through more boron atoms to make up the numbers, forming limited stable compounds. In 4D space with hydrogen (H) and tritium (T), it’s easy to break through these limitations, allowing more elements to have five bonding orbitals. Specific examples can be found in the 4D molecular browser.

Aromatic Hydrocarbons

The previous article mentioned that according to unsaturation (or hybridization type), there are four types of aliphatic hydrocarbons: alkanes, alkones, alkenes, and alkynes. Methane has sp4 4D regular 5-cellular structure. Due to the $\pi$ electron cloud of double bonds, all atoms of ethone are restricted to the flat cell perpendicular to the unhybridized $p$ orbital. Ethene has two pairs of mutually perpendicular unhybridized $p$ orbitals, and all atoms are restricted to the plane perpendicular to them, making it a planar molecule like three-dimensional ethylene. The analog of benzene has two types: sp3 and sp2 hybridization. The sp3 hybridized one is a spatial hexagon, i.e., C6D12 (I name it shrinone), while the sp2 hybridized one is a planar hexagon, i.e., C6D6 (I name it benzene).

Note: Hückel’s $4n+2$ electron rule for determining aromaticity (derived from molecular orbital theory) analogizes to $8n+4$ electron rule in 4D. You can verify that shrinone satisfies this rule, while 4D benzene has two sets of perpendicular $p$ orbitals that each form delocalized large $\pi$ bonds without interfering with each other, each satisfying Hückel’s rule, having very stable double aromaticity.

Spatial Isomerism

Organic compound structures are very rich and usually require consideration of spatial isomerism. Let’s see how chiral isomerism and cis-trans isomerism analogize to 4D.

Chiral Isomerism and Sugars

4D molecules also have chiral isomerism, with optical activity similar to 3D. Atoms connected to five different groups are chiral atoms. Worth noting is that three-dimensional glucose and galactose originally differ only in two chiral carbons. When analogized to 4D, carbon changes from tetravalent to pentavalent. Whether connecting deuterium or deuterioxyl groups, there will be two identical groups on carbon losing chirality. That is, in the 4D world, glucose and galactose, sucrose and lactose no longer differ and have no optical activity. As an aside: if avoiding the unstable situation of two hydroxyl groups on one carbon, sugar compounds without carbonyl groups can hardly be equivalent to carbohydrates (CmD2nOn). I only found one type of diethyl sugar (C4O6D12) that is a carbohydrate.

Double Bond Cis-Trans Isomerism

Atoms at both ends of a double bond each connect to three groups. Four atoms on each side determine a three-dimensional space (cell). Due to the appearance of pi orbitals perpendicular to that cell, both sides must be coplanar. This will lead to a new isomerism phenomenon mixing three-dimensional chiral isomerism and cis-trans isomerism: double bonds can rotate in the space perpendicular to pi orbitals, but cannot independently flip in 4D space, so they are either homochiral or heterochiral.

Triple Bond Cis-Trans Isomerism

The situation at both ends of triple bonds is simple, just like ordinary cis-trans isomerism in three-dimensional space, with two isomers.

Cumulative Double-Triple Bond Isomerism

4D molecules also have cumulative double-triple bonds: the central atom is sp hybridized, connecting adjacent atoms in a straight line. This is a direct analog of three-dimensional cumulative double bonds. Let the straight line direction be the x-axis, with four atoms at the double bond end in xyz space and the unhybridized p orbital of the double bond in the w direction. Then the two unhybridized p orbitals of the triple bond can only be in the remaining y and z directions, and the three atoms at the triple bond end are limited to the xw plane. This figure also has isomerism: if atoms on both sides are all different, imagine we try to exchange the other two atoms at the triple bond end by rotation - we must rotate the molecule in a plane containing the w axis but not the x axis. This will inevitably reverse one coordinate axis in xyz space, simultaneously changing the order at the double bond end. Therefore, it also has two cases similar to double bond cis-trans isomerism.

Cumulative Double Bond Isomerism

4D molecules also have a type of cumulative double bond that simultaneously has structural characteristics of both cumulative double bonds and ordinary double bonds in three-dimensional space - the most complex case. Carbon atoms in cumulative double bonds adopt sp2 hybridization, so three atoms connected to it are coplanar, with two pairs of $p$ orbitals perpendicular to each other and both perpendicular to that plane. If we place this plane on the xy plane, then one $\pi$ bond is in the z direction and one $\pi$ bond is in the w direction. The four atoms at both ends are in xyz and xyw three-dimensional spaces respectively. The middle cumulative double bond carbon atom also has a single bond connecting to another atom (or lone electron orbital), but this atom has a planar structure around it and can flip freely in 4D space, not satisfying chiral conditions. Therefore, like ordinary double bonds, there’s only one set of cis-trans isomers. We can define two types of molecules this way: first choose an end carbon A, label them as A, B, C in order. After giving the order of connecting atom groups, we can take the cross product of three vectors in order to get the normal vector of the cell formed by the end carbon and three atoms. Take the cross product of normal vectors m and n of cells containing groups on carbon A and carbon C to form a 2-vector m$\wedge$n. This vector is theoretically absolutely perpendicular to AB$\wedge$BC (i.e., the plane containing three carbons), so their inner product is 0. We can distinguish two chiralities by the sign of the cross product.

4D Crystal Systems

All crystal structures in three-dimensional space can be divided into 7 crystal systems (triclinic, monoclinic, orthorhombic, tetragonal, cubic, trigonal, hexagonal) and 14 Bravais lattices. All crystal structures in 4D space can be divided into 23 crystal systems and 64 Bravais lattices, of which 10 also have chirality. The Wikipedia “Crystal System” entry and “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” both list the specific 23 crystal systems. “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” provides a crystal parameter table.

Below is my analysis of the 23 crystal systems with crystal axis coordinate expressions:

Hexaclinic: The most general parallelepiped with no special symmetry. All crystal faces are oblique, all crystal axes are oblique, angles between crystal axes are not 90°, and angles between crystal faces are not 90°. After choosing an appropriate coordinate system, the four column vectors can form the most general upper triangular matrix:$$\begin{pmatrix}a&b&d&g \\ 0 &c&e&h\\ 0 &0&f&i \\ 0 &0&0&j\end{pmatrix}$$

Triclinic: An oblique prism with a rectangular base cell, where the angles between the generatrix direction and the three edges of the base cell are all not 90°.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&d \\ 0 &b&0&e\\ 0 &0&c&f \\ 0 &0&0&g\end{pmatrix}$$

Diclinic: A type of oblique prism. The base cell is an oblique rectangular prism, with its tilt direction parallel to one edge of the rectangle, and the generatrix tilt direction of the entire 4D prism parallel to another edge of the rectangle, i.e., two generatrices each tilted in two perpendicular directions. Can also be seen as the direct sum of any two 2D lattices without special symmetry.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&c&0 \\ 0 &b&0&e\\ 0 &0&d&0 \\ 0 &0&0&f\end{pmatrix}$$

Monoclinic: An oblique prism with a rectangular base cell, where only one of the angles between the generatrix direction and the three edges of the base cell is not 90°, i.e., tilted only in that direction.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&d \\ 0 &b&0&0\\ 0 &0&c&0 \\ 0&0&0&e\end{pmatrix}$$

Orthogonal: Hyperrectangle, all axes are at right angles to each other, but axis lengths are unequal.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&0 \\ 0 &b&0&0\\ 0 &0&c&0 \\ 0&0&0&d\end{pmatrix}$$

Tetragonal monoclinic: An oblique prism with a square prism base cell, where only one angle between the generatrix direction and the three edges of the base cell is not 90°, tilted only in the height direction of the square prism. Can be seen as the direct sum of a square lattice and any 2D lattice without special symmetry.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&c \\ 0 &b&0&0\\ 0 &0&b&0 \\ 0&0&0&d\end{pmatrix}$$

Hexagonal monoclinic: An oblique prism with a regular hexagonal prism base cell, where only one angle between the generatrix direction and the three edges of the base cell is not 90°, tilted only in the height direction of the hexagonal prism. Can be seen as the direct sum of a regular triangular lattice and any 2D lattice without special symmetry.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&c \\ 0 &b&-{b\over2}&0\\ 0 &0&{\sqrt{3}b\over2}&0 \\ 0&0&0&d\end{pmatrix}$$

Ditetragonal diclinic: Two squares of different sizes with their planes in equiangular relationship, with left and right chirality.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&b&-c \\ 0 &a&c&b\\ 0 &0&d&0 \\ 0&0&0&d\end{pmatrix}$$

Ditrigonal (dihexagonal) diclinic: Two regular hexagons of different sizes with their planes in equiangular relationship, with left and right chirality.$$\begin{pmatrix}a\cos(\theta)&a{\sqrt{3}\sin(\theta)-\cos(\theta)\over 2}&b\cos(\phi)&-b{\cos(\phi) \over 2}\\ -a\sin(\theta) &a{\sqrt{3}\cos(\theta)+\sin(\theta)\over 2}&0&b{\sqrt{3}\cos(\phi) \over 2}\\ 0 &0&b\sin(\phi)&-b{\sin(\phi) \over 2} \\ 0&0&0&b{\sqrt{3}\sin(\phi) \over 2}\end{pmatrix}$$

Tetragonal orthogonal: A hyperrectangle with two equal edges.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&0 \\ 0 &a&0&0\\ 0 &0&b&0 \\ 0&0&0&c\end{pmatrix}$$

Hexagonal orthogonal: A right prism with a regular hexagonal prism base cell, with two unequal heights, the direct product of a regular hexagon and rectangle.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&-{a\over 2}&0&0 \\ 0 &{\sqrt{3}a\over 2}&0&0\\ 0 &0&b&0 \\ 0&0&0&c\end{pmatrix}$$

Ditetragonal monoclinic: Two squares of different sizes with their planes in equiangular relationship, with left and right chirality, and the projections of these two lattice basis vectors onto each other’s planes are aligned with each other’s lattice basis vectors.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&b&0 \\ 0 &a&0&b\\ 0 &0&c&0 \\ 0&0&0&c\end{pmatrix}$$

Ditrigonal (dihexagonal) monoclinic: Two regular hexagons of different sizes with their planes in equiangular relationship, with left and right chirality, and the projections of these two lattice basis vectors onto each other’s planes are aligned with each other’s lattice basis vectors.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&-{a\over 2}&b\cos(\phi)&-b{\cos(\phi) \over 2}\\ 0 &{\sqrt{3}a\over 2}&0&b{\sqrt{3}\cos(\phi) \over 2}\\ 0 &0&b\sin(\phi)&-b{\sin(\phi) \over 2} \\ 0&0&0&b{\sqrt{3}\sin(\phi) \over 2}\end{pmatrix}$$

Ditetragonal orthogonal: A hyperrectangle with two pairs of equal edges respectively, the direct product of two squares of different sizes.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&0 \\ 0 &a&0&0\\ 0 &0&b&0 \\ 0&0&0&b\end{pmatrix}$$

Hexagonal tetragonal: A right prism with a regular hexagonal prism base cell, with two equal heights, the direct product of a regular hexagon and square.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&-{a\over 2}&0&0 \\ 0 &{\sqrt{3}a\over 2}&0&0\\ 0 &0&b&0 \\ 0&0&0&b\end{pmatrix}$$

Dihexagonal orthogonal: Direct product form of two unequal regular hexagons, equivalent to the case where two planes in dihexagonal mono/diclinic systems are absolutely perpendicular.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&-{a\over 2}&0&0 \\ 0 &{\sqrt{3}a\over 2}&0&0\\ 0 &0&b&-{b\over 2} \\ 0&0&0 &{\sqrt{3}b\over 2}\end{pmatrix}$$

Cubic orthogonal: A hyperrectangle with a cubic base cell, all axes at right angles to each other, with only one edge having a different length from the other three.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&0 \\ 0 &a&0&0\\ 0 &0&a&0 \\ 0&0&0&b\end{pmatrix}$$

Octagonal: Two equal squares with an adjustable angle parameter between their planes, extreme cases being hypercubic system and coplanar two equal squares 45 degrees apart in 2D tetragonal system, with two planes transitioning from absolutely perpendicular to coplanar fully parallel. In non-extreme states there’s chirality between two planes, a special case of ditetragonal diclinic parameters where $b=c$ and all axis lengths are equal.$$\begin{pmatrix}\sqrt{2b^2+a^2}&0&b&-b \\ 0 &\sqrt{2b^2+a^2}&b&b\\ 0 &0&a&0 \\ 0&0&0&a\end{pmatrix}$$

Decagonal: Obtained by stretching the highly symmetric icosahedral system along one axis, similar to the relationship between cubic orthogonal and hypercubic.$$\begin{pmatrix}k a&a&a&a \\ a&k a&a&a\\a&a&k a&a\\ a&a&a&k a\end{pmatrix}$$

Dodecagonal: Two equal regular hexagons with an adjustable angle parameter between their planes between 90 and 60 degrees, extreme cases being hexagonal tetragonal system and coplanar 3D face-centered closest packing, with two planes transitioning from absolutely perpendicular to coplanar semi-parallel. In non-extreme states there’s chirality between two planes, specific associated geometric meaning unclear.$$\begin{pmatrix}1&-\frac{1}{2}&e&0\\0&\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}&\frac{e}{\sqrt{3}}&\frac{2e}{\sqrt{3}}\\0&0&\sqrt{1-\frac{4e^2}{3}}&\frac{-4e^2-3}{2\sqrt{9-12e^2}}\\0&0&0&\sqrt{\frac{16e^4-40e^2+9}{12-16e^2}}\\ \end{pmatrix}$$

Diisohexagonal orthogonal: Direct product form of two equal regular hexagons.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&-{a\over 2}&0&0 \\ 0 &{\sqrt{3}a\over 2}&0&0\\ 0 &0&a&-{a\over 2} \\ 0&0&0 &{\sqrt{3}a\over 2}\end{pmatrix}$$

Icosagonal (icosahedral): The lattice is a parallelepiped spanned by the body center of a regular 5-cell and its four vertices. Has overall regular 5-cell symmetry, with all edge lengths and angles equal. In this arrangement, each atom is adjacent to 10 equidistant surrounding atoms, and these 10 atoms are arranged as vertices of two mutually dual regular 5-cells.$$\begin{pmatrix}k a&a&a&a \\ a&k a&a&a\\a&a&k a&a\\ a&a&a&k a\end{pmatrix}$$where: $k=\sqrt{5}-4$.

Hypercubic: A hypercube with all edges equal length and all angles right angles.$$\begin{pmatrix}a&0&0&0 \\ 0 &a&0&0\\ 0 &0&a&0 \\ 0&0&0&a\end{pmatrix}$$

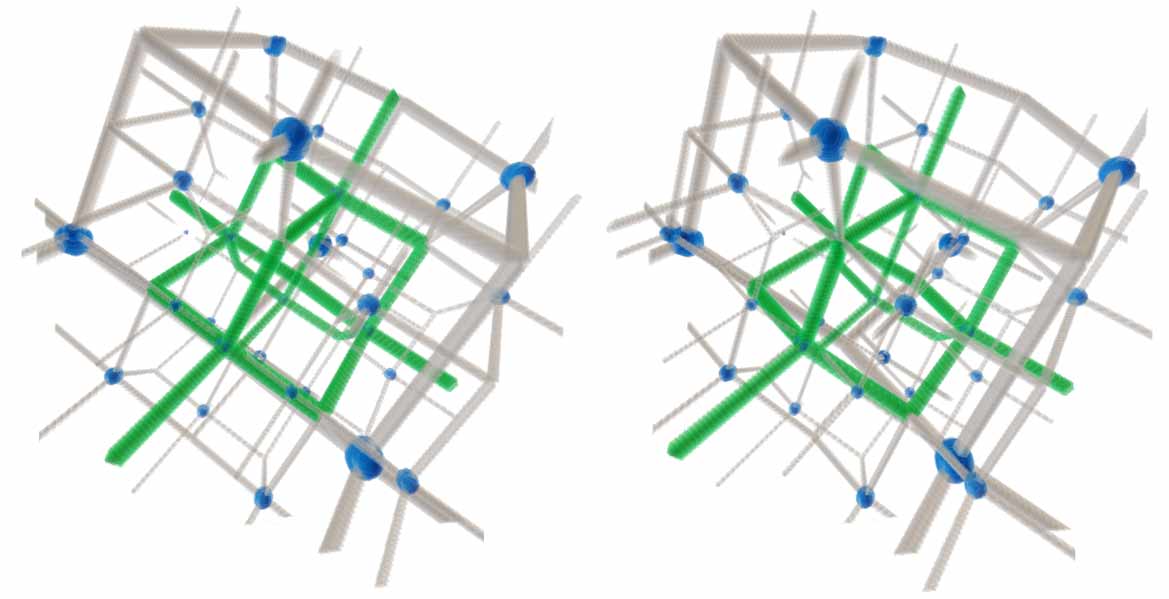

Note: In Tesserxel under Material Structures > 4D Lattices, there are lattice models with good symmetry available for viewing.

Diamond Structure Analogy

Diamond and graphite are both allotropes of carbon element. 4D carbon allotropes are divided into three types according to hybridization type:

- sp2 hybridized planar graphite structure, a two-dimensional sheet structure where each carbon atom has two mutually perpendicular unhybridized p orbitals forming two independent delocalized large $\pi$ bonds, similarly conductive and can be used as lubricant;

- sp3 hybridized “diamond-graphite” structure, a three-dimensional diamond sheet cell layered structure where each carbon atom has unhybridized p orbitals perpendicular to the sheet cell layer forming delocalized large $\pi$ bonds, conductive, with only van der Waals forces between layers allowing sliding, can be used as lubricant;

- sp4 hybridized hyperdiamond structure;

Hyperdiamond is a completely new 4D structure. We need to study its structure. Let’s assume each carbon connects to five adjacent carbons, with bond angles all being standard sp4 hybridized regular 5-cell bond angles, and each carbon atom and each carbon-carbon bond having the same status. Is there such a structure? Three-dimensional diamond has face-centered cubic structure. Three-dimensional diamondoid can be seen as taking regular tetrahedron vertices and edge centers as the backbone, then pulling edge center atoms outward until vertices and edge center atoms satisfy sp3 bond angle requirements. Both cubes and regular tetrahedra appear here because taking alternate half vertices of a cube gives a regular tetrahedron, while taking alternate half vertices of a hypercube gives a regular 16-cell - analogy fails. 4D space can still have hyperdiamondoid structure, i.e., taking regular 5-cell vertices and edge centers as backbone and similarly pulling outward. But can we ensure both vertices and edge centers simultaneously satisfy ideal sp4 hybridization angles? There’s a simple method to verify without complex calculations: when pulled until the two line segments from edge center to vertex are parallel to the line from vertex to regular 5-cell center, according to equal opposite angles in parallelograms, these angles must all equal the ideal sp4 hybridization angle. Drawn in Tesserxel, we can find this model satisfies vertex and edge symmetry. This shows that hyperdiamond crystal structure is not in the hypercubic system family, but belongs to the 4D icosahedral system family. Diphosphorus pentoxide also has diamondoid structure, analogized to 4D might have a hyperdiamondoid structure of pentahesperus pentadecaoxide. 4D diphosphorus pentoxide and higher oxidation state diphosphorus heptoxide also exist - they are tetraphosphorus decaoxide and tetraphosphorus tetradecaoxide similar to three-dimensional diamondoid structure, just with different numbers of coordinated oxygens. (Hesperus (G) atomic number: 36, valence electron configuration: 3s43p8, entron group, common valence 4; Phosphorus (P) atomic number: 38, valence electron configuration: 3s43p10, nitrogen group, common valence 3.)

Diphosphorus pentoxide also has diamondoid structure, analogized to 4D might have a hyperdiamondoid structure of pentahesperus pentadecaoxide. 4D diphosphorus pentoxide and higher oxidation state diphosphorus heptoxide also exist - they are tetraphosphorus decaoxide and tetraphosphorus tetradecaoxide similar to three-dimensional diamondoid structure, just with different numbers of coordinated oxygens. (Hesperus (G) atomic number: 36, valence electron configuration: 3s43p8, entron group, common valence 4; Phosphorus (P) atomic number: 38, valence electron configuration: 3s43p10, nitrogen group, common valence 3.)

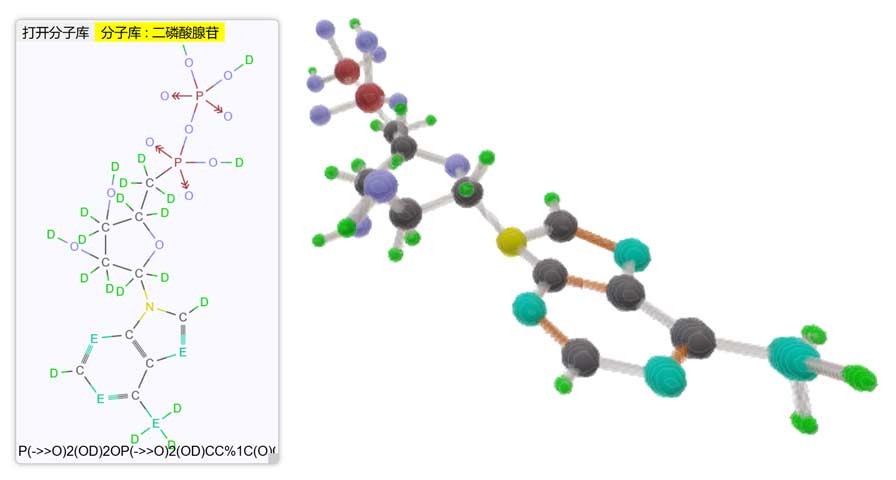

4D Molecular Browser

Although we know very little about “real” 4D chemistry, for fun I still wrote a hypothetical 4D chemistry common substance structure viewer that supports interaction with the Tesserxel example library to generate 4D molecular models. (There’s a bug in 2D structural formula display involving diamondoid, please ignore) I also named some functional groups myself, while adopting some names from “Symmetric 4D Chemistry”, such as the functional group “Dione” (-CO2), analogs of certain amino acid structures, etc.

Each refresh randomly generates molecules, or click “I’m feeling lucky” to get the next molecule. Randomly generated molecules are saved to the history record.

Particle Physics

Since corrections must be made for atomic instability caused by 4D inverse cube law, atomic and molecular properties would be greatly affected, and these simple analogies might all fail. The ideal way to build a 4D worldview is to directly specify the most basic “God” physical laws, then everything else doesn’t need to be set - derive all physics, chemistry, nature and even biology-related properties from there. In the real world, these “God” physical laws haven’t been completely discovered yet. The closest physical theories currently are quantum field theory and general relativity. However, quantization of gravity hasn’t been solved, and quantum field theory cannot be compatible with general relativity. String theory is a possible final theory integrating both, but currently there’s no experimental evidence supporting it. In this article, we’ll first ignore gravity and focus only on quantum field theory.

Introduction to Quantum Field Theory

Quantum mechanics tells us that microscopic particles exist in the form of probability waves. The Schrödinger equation describes how the position probability wave function of a single particle evolves over time. However, as research deepened, people found that all particles are quantum fields. Describing particle positions in three-dimensional space has three degrees of freedom, but describing a field requires giving field values at every point in space - infinite degrees of freedom. The entire quantum field’s various different distribution values all have independent probabilities, and its probability wave function also becomes infinite-dimensional. Therefore, we don’t directly solve for wave functions like the Schrödinger equation, but use techniques related to Feynman diagrams to calculate the sum of probability amplitudes contributed by all possible evolution paths of particle interactions to predict physical experimental results. This is the basic mathematical logic of quantum field theory.

Quantum field theory believes that the entire universe space is permeated with quantum fields, and particles are excited states of fields, similar to vibration modes described by wave functions. Each type of elementary particle corresponds to a quantum field, such as electron field, photon field, etc. Interactions between particles are essentially coupling between fields: for example, two electrons (electron field) produce repulsive force by exchanging photons (vibrations of electromagnetic field). Quantum field theory is compatible with special relativity (excluding gravity) and is currently the most precisely experimentally verified physical theory.

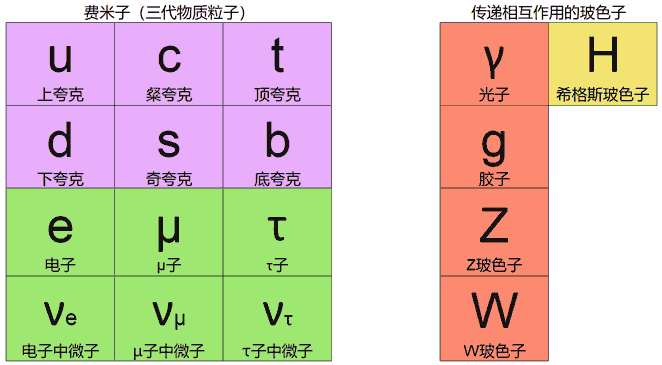

Standard Model

What elementary particles are there exactly? The standard model gives all particles and their interactions. Fermions are particles with half-spin that constitute matter, such as electrons, quarks, etc. The 6 types of quarks are marked in pink, the 6 types of leptons are marked in green. Leptons have much smaller mass than quarks, hence the name. They’re divided into 3 columns called “generations”. Corresponding particles in different generations have little difference in properties except mass. From left to right are the first, second, and third generations. Our normal atoms are all composed of first-generation quarks (up and down quarks forming protons and neutrons) and electrons.

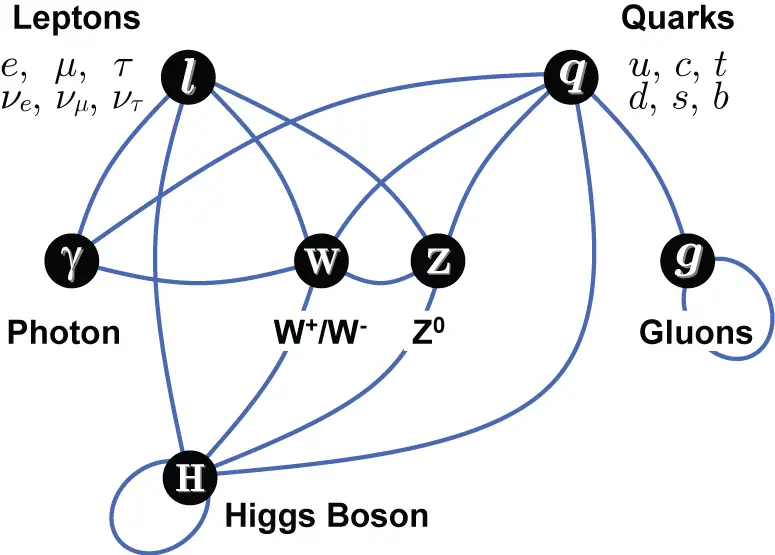

How do these particles interact? Electrons and quarks carry electric charge and interact with electromagnetic fields (photons); quarks and gluons carry “color charge” and undergo strong force interactions through gluons, binding protons and neutrons to form atomic nuclei; additionally, left-handed fermions have weak interactions transmitted through W and Z bosons, which cause radioactive decay of atomic nuclei, while neutrinos carry no charge and only participate in weak interactions and gravitational interactions; finally, the Higgs boson gives mass to all fermions and W, Z bosons.

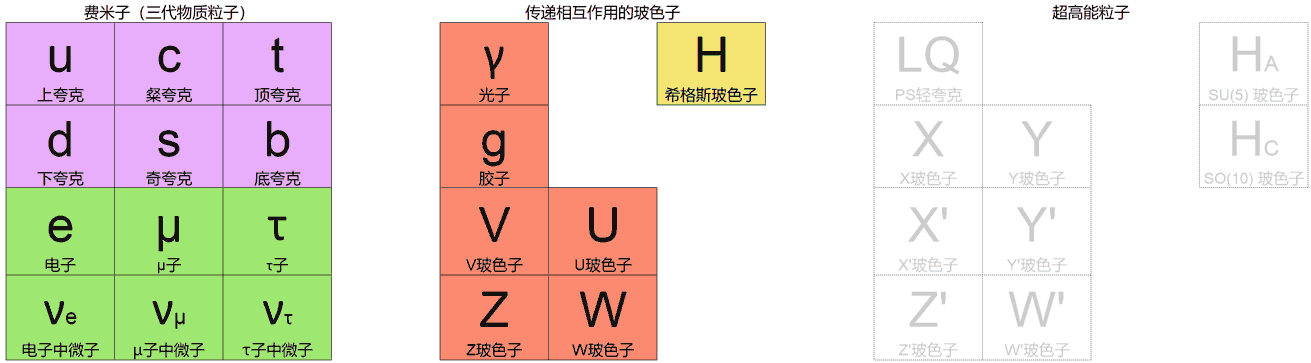

Standard Model of 4D Field Theory

The inverse cube decay law in 4D space means that if electrons only experience electromagnetic force from atomic nuclei, there are no longer discrete lowest energy states - electrons would continuously radiate energy and eventually fall into the nucleus. Therefore, we need to introduce physical mechanisms different from the real world to eliminate this. There’s no standard solution for avoiding 4D atomic instability. For example, this paper found that hydrogen atoms in five dimensions and above might have discrete energy levels, but the dimensions don’t apply to 4D; Hadroncfy believes directly using three-dimensional models, although causing atomic instability, might have stable molecular orbitals, but I think hope is slim - interested friends can calculate and explore themselves.

Here I first need to introduce the new standard model proposed in “Symmetric 4D Chemistry”: by adding new fermion three-generation symmetry $\mathrm{U}(3)$ on top of the existing $\mathrm{SO}(10)$ symmetry grand unified theory (GUT) to introduce new interactions that both exchange 3 generations of fermions (by U bosons) and produce slight repulsive force between same-generation matter (by V bosons). This repulsive force can prevent electrons from spiraling into the nucleus, making atomic stability possible.

This model looks great, but the author also admits it was just made for fun and it’s hard to say if it really gives the correct microscopic theory of the 4D world. Because the standard model has many parameters, various particles in the model all require rigorous calculation to know if they satisfy stability. Currently everyone just qualitatively gives particle models without being able to definitively know if all instability and renormalization divergence problems in the 4D world have been completely solved, thus building a physically most “real” 4D world from bottom up.

4DEnthusiast’s Estimation of Alkali Metal Properties

Interestingly, 4DEnthusiast’s imagined 4D chemistry also adopts introducing new massive spin-1 vector bosons to create short-range repulsive force preventing electron collapse, though he didn’t propose other supersymmetric models including exchanging fermions between generations.

Through calculations, he found that 4D atomic radii would change very dramatically: in the three-dimensional world, the radius ratio between smallest hydrogen and largest cesium elements is at most 10 times, but in 4D with exponentially decaying short-range force introduced, this ratio can reach hundreds of times, with volume ratios reaching 10 to the 8th power. They almost cannot appear as non-ionized elements. If elemental forms were somehow isolated, they could form stable plasmas at room temperature, and this gas could reduce almost all substances in contact with it. At sufficiently low temperatures, they might condense to form metals millions of times lighter than ordinary solids with extremely low density. Since any visible photon can easily cause electrons to escape from such metals, 4DEnthusiast speculates 4D alkali metals might appear deep red or even black. 4DEnthusiast didn’t say these alkali-like metals are all first-column elements of the periodic table, because through angular momentum calculations he found that energy differences corresponding to principal quantum numbers and angular quantum numbers analogized from three to 4D might be so large that periodic law becomes chaotic, causing energy level crossing rules to completely disappear, and all versions of periodic tables we gave before might be wrong. Currently he hasn’t given a specific periodic table.

4D Nuclear Shell Model

4DEnthusiast believes internal nuclear details are mostly unrelated to chemistry because they’re much smaller than ordinary electron orbitals and can usually be treated as point structures. However, nuclear physics determines which elements exist and their abundances, so it’s still worth considering. “Symmetric 4D Chemistry” proposed a nuclear shell model that can estimate whether various atoms are radioactive or their radioactive half-lives: like calculating how many electrons are needed per layer to reach noble gas stable structure for electron orbitals, the same can be calculated for numbers of protons and neutrons filling nuclear layers, though for nuclei coupling of spin angular momentum and orbital angular momentum also needs consideration. They also drafted some helium fusion, helium capture and other nuclear reaction formulas, trying to explain stellar evolution. 4DEnthusiast believes introducing new short-range forces would make electron-nucleon interactions very different: assuming the weak reaction $p + e^- \rightarrow n + \nu_e$ can still occur, and the “s-charge” (similar to electric charge for electromagnetic force) corresponding to short-range force is conserved before and after reaction. According to this reaction formula, electrons carry s-charge while neutrinos carry no s-charge (otherwise would interfere with chemical reactions), so neutrons must carry some s-charge. The simplest idea is to let neutrons and electrons carry the same s-charge while protons carry no s-charge, but this would cause electrons to mainly interact through short-range force rather than weak force. To avoid this situation, nucleon s-charges need to be much larger than electron s-charges, with neutron s-charge slightly more than proton’s, thus maintaining s-charge conservation in the above weak reaction equation. Since neutrons carry s-charge, nuclides with same proton number but different neutron numbers would have significantly different chemical properties, to the point they might be considered completely different elements. This also means in nuclides with sufficiently high proton-neutron ratio, electrons can completely overcome s-force to fall into nuclei for absorption and transformation into new nuclides. Despite such large differences, 4DEnthusiast believes organic compound backbone elements would still be near normal carbon element.

Other Periodic Law Worldview Settings

“Symmetric 4D Chemistry” gave two other different periodic law settings: the first is Vector’s 2-spin electron system proposed in Higher Space forum, which is actually also 4DEnthusiast’s setting: assuming the 4D world only has electrons with one chiral spin (like left equiangular rotation), while positrons all have the other chiral spin. This article’s 4D setting assumes both types of electrons exist simultaneously in almost equal proportions. Which mode the “real” 4D world adopts can only be determined experimentally: imagine two worlds originally with only left-handed and right-handed electrons (if naturally a four-spin state world, different chiral electrons can also be forcibly separated through chiral magnetic field screening to form single-chirality atoms). One day they meet, and elements between the two worlds start frantically exchanging each other’s electrons, finally reaching a structure balanced in both chiralities. All elements change from two-spin periodic law to four-spin periodic law while atomic numbers remain unchanged. For example: the originally inert element helium (under two-spin periodic law meaning) filled with two electrons suddenly discovers the orbitals for filling the other side’s chiral electrons are still empty, so they each exchange one electron to become two atoms with atomic number 2 - deuterium atoms (under four-spin periodic law meaning), then form D2 molecules. Note this process doesn’t change nuclei or atomic numbers, so it’s a peculiar chemical reaction rather than nuclear reaction.

The second ignores the fact that orbital angular momentum must be simple 2-vectors, forcibly considering left and right equiangular rotation waves as independent and freely combinable into some very strange combinations: now each electron is represented not just by single letters s, p, d, but double letters like ss, sp, ps, sd, pp, causing even more frightening numbers of elements: Based on this model they also proposed nuclear physics, molecular multi-center bonds and other settings. However, mathematical calculations show non-simple 2-vector orbital angular momentum is self-inconsistent and can be directly determined as incorrect theory, but imagining it for fun isn’t bad either.

Based on this model they also proposed nuclear physics, molecular multi-center bonds and other settings. However, mathematical calculations show non-simple 2-vector orbital angular momentum is self-inconsistent and can be directly determined as incorrect theory, but imagining it for fun isn’t bad either.

Personally I think the 2-spin electron system, though similar to 3D, is also geometrically far-fetched, because choosing only two rotation directions rather than four in 4D space directly breaks parity (chirality). But at least it doesn’t violate mathematical principles. Well, our world also violates parity conservation anyway… Actually since the 4D world is fake anyway, it doesn’t matter. Below are related links:

- Alternative Chemistries: 4DEnthusiast’s 4D chemistry, including particle physics settings, 4D bond energy calculations, element property predictions and other hardcore content. Electrons adopt chiral two-spin state setting. (Currently the most detailed 4D microscopic physics setting seen, though it also hasn’t solved the non-renormalizable problem)

- Symmetric 4D Chemistry: Four-spin state system with same setting as this blog

- Vector’s 4D Chemistry: Chiral two-spin state electron setting published on Higher Space forum

- Planet’s 4D Chemistry: Four-spin state system allowing non-simple orbital angular momentum, inspiration source for Symmetric 4D Chemistry

- Quack’s Old 4D Chemistry: Old system of Symmetric 4D Chemistry, also a four-spin state system allowing non-simple orbital angular momentum

Reference Answers for Previous Article

- Protium and oxygen form H4O (oxoshania), deuterium and oxygen form D2O (water).

- For water in the 4D world, see 4D ocean section.

- Benzene in the 4D world might include: C6D6 (benzene), C6D12 (shrinone), C6H12 (hexaprotenylbenzene), Tk6H6 (tinkarobenzene), Qc6T6 (Quietacobenzene), etc.

- The elemental form of tritium is most likely the tetrahedral tetratomic molecule T4. The s orbitals of four atoms overlap and linearly combine into three filled lower-energy bonding orbitals and one empty higher-energy non-bonding orbital, forming a 4-center 12-electron bond. See Molecular orbital theory section for this topic.