4D World (III): Road and Railway Design

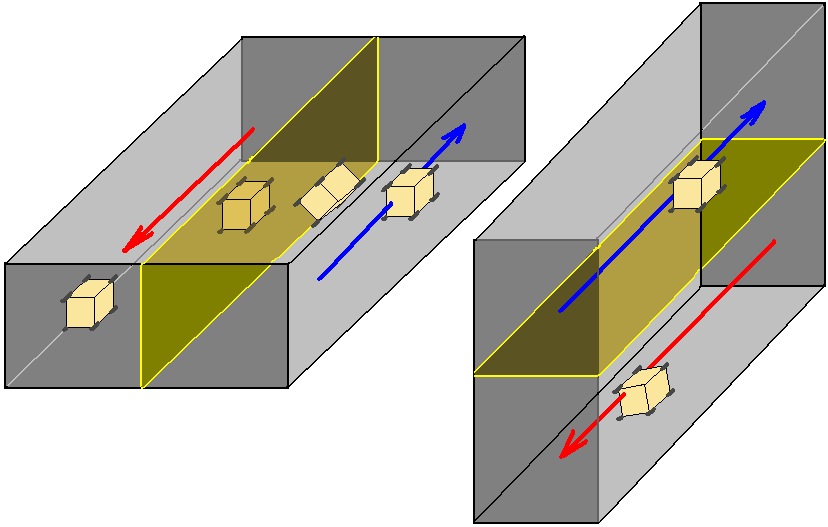

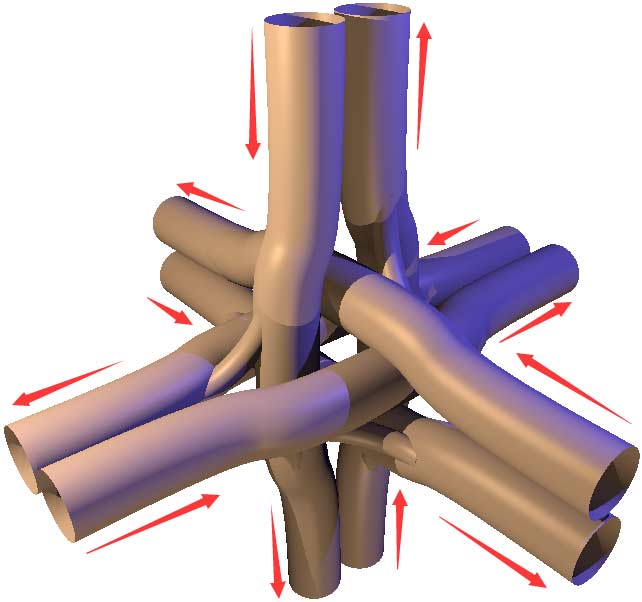

The previous article introduced various types of vehicles in the four-dimensional world, all of which can freely drive and steer on three-dimensional ground surfaces. Since four-dimensional space doesn’t require traffic lights and overpasses, does this mean transportation for four-dimensional beings is extremely convenient? Yes, but four-dimensional traffic still has some minor issues. We know that in three-dimensional space there are two-way roads with median strips or yellow lines separating them, and everyone follows the rule of keeping to the right; in the four-dimensional world’s two-way roads, the median barrier on the three-dimensional road surface must be two-dimensional to separate the roads - drawing a single line no longer serves this purpose. The simplest two-way road would probably look like this:

As we can see, it’s like a blood vessel, where cars inside can move freely at various angles like cells, as long as the front of the car points forward. Whether the road’s cross-section should be circular is indeed a question, because even if cars are approximately hyper-rectangular, the car’s free rotation means the corners of a square cross-section aren’t efficiently utilized. Of course, we could align the car’s rotation with the road’s cross-section, but as we’ll see, this is cumbersome and unnatural. Due to this directional arbitrariness, following the keep-right principle becomes meaningless - 4D beings must mark driving directions everywhere on highways to prevent vehicles from entering and driving against traffic.

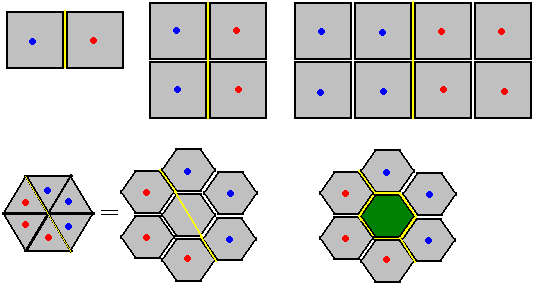

As for multi-lane roads, this becomes entirely a two-dimensional problem of allocating cross-sectional space. Below are some possible multi-lane patterns: (Blue represents traffic direction perpendicular to the page going inward, red represents outward)

Since cars can rotate freely, we’d better make the lane cross-sections nearly circular. The densest packing of two-dimensional circles is equivalent to hexagonal honeycomb patterns, which maximizes space utilization, though I can’t figure out who should use the centermost lane - if all else fails, just make it a green belt. Note that the triangular lane pattern in the bottom left is essentially the same as the honeycomb lane pattern, with the central area still able to accommodate one more lane.

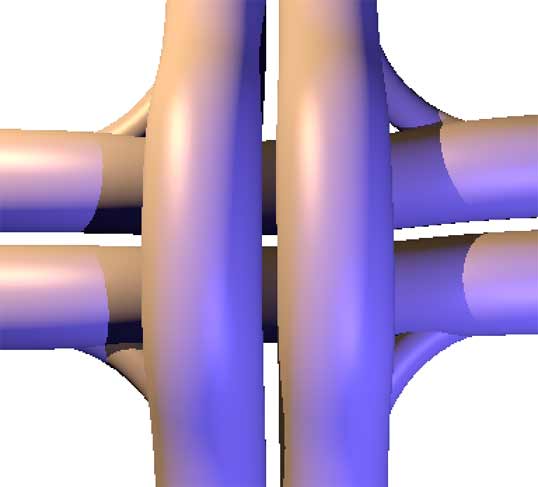

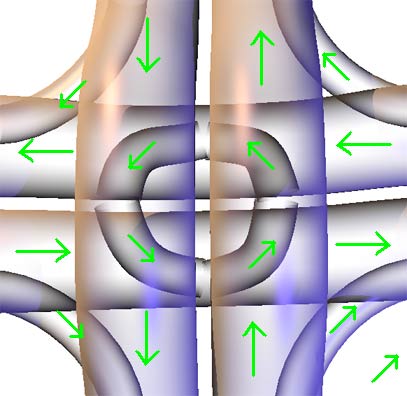

Now let’s look at intersection design. Since the reason we don’t need overpasses is that three-dimensional ground has enough space to pass through, and our three-dimensional world’s overpasses work by overcoming gravity to gain enough passing space, the simplest idea is to directly lay our world’s interchanges flat on the three-dimensional ground. But since there’s no longer a gravity constraint, left-turning vehicles can dart directly from “above the bridge” to “below the bridge.”

But in four-dimensional world cities, there will also be situations where three perpendicular roads directly intersect, for which we have no corresponding experience. However, by analogy with previous cases, we can still roughly design a solution, though I believe there must be more symmetrical and elegant solutions.

Railways

Now let’s look at railways: Railway directions are fixed, so they’re simpler than cars. However, the shape of railway tracks and train wheels, as well as the design of switches and stations, are actually worth discussing. Let’s first look at the construction of three-dimensional train wheels: To prevent derailment, wheels have protruding flange structures, and the cross-section of the two rails is I-shaped.

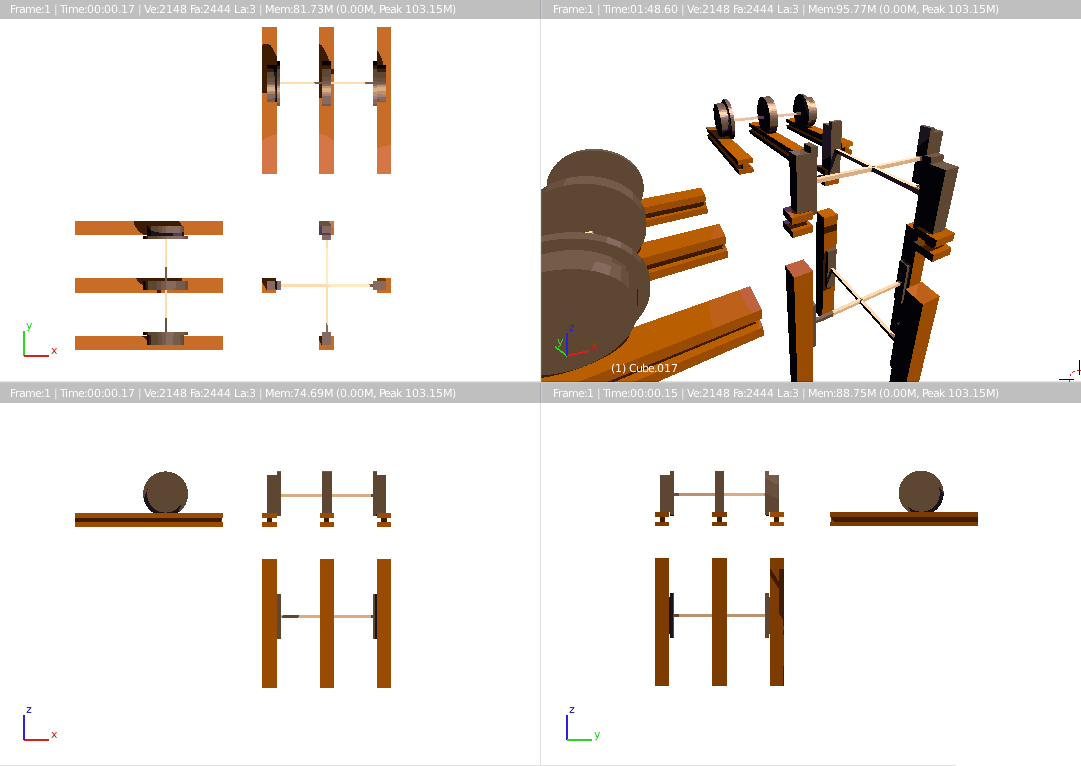

First, let’s assume trains are hyper-rectangular. What would four-dimensional rails look like? One approach is: rails are equivalent to road curbs, so the four-dimensional rail should look like a cylinder or square tube from above, like blood vessel walls. But this isn’t actually necessary. Since there are four wheels on the same cross-section (the plane perpendicular to the direction of travel on the ground), we only need four rails to constrain these four wheels. This not only saves materials but also makes switch construction simpler. The train tracks in the block4d game I mentioned in the previous article are displayed using this four-rail method. Of course, you can also build three-rail, five-rail, or n-rail railways - we’ve already shown the corresponding wheel distributions for such trains in the previous article. What about the specific shape of the tracks? Let’s roughly consider the I-beam track cross-section as rectangular, since the I-beam difference is just about saving materials. The four-dimensional track cross-section is a three-dimensional figure, so we can try rectangular prisms and cylinders first. Why not try spheres? Because this cross-section has one direction parallel to the vertical direction, making a cylinder more appropriate. At most, we might carve out parts of the cylinder to save material, creating a dumbbell shape that’s thick at both ends and thin in the middle.

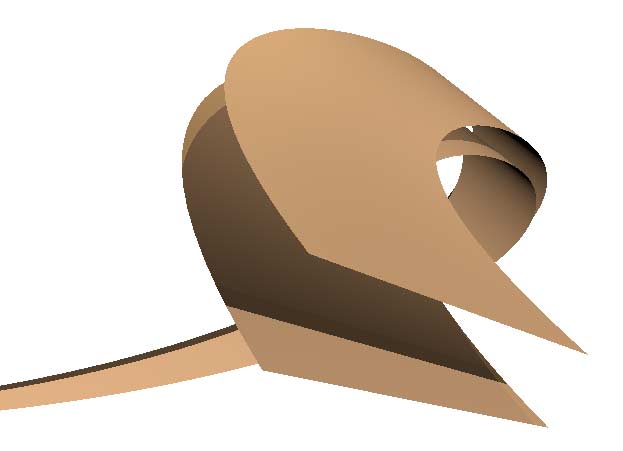

We divide the train wheel into two parts: one is the flange, the other is the part that sits on the rail. The top view is most convincing: it reflects the entire wheel’s shape. We might first think of both the wheel and flange as bi-cylinders, just with different radii. But bi-cylindrical flanges cannot fit tightly with the guide rails, so square cylinders might be more suitable here. Similarly, the rail’s cross-sectional shape can also be more square - only with good fit can the rail’s guiding ability for the flange be stronger, otherwise derailment is likely.

Is this design perfect? If we run trains like this now, the consequences would be disastrous: we’ve ignored one type of motion - the train will derail with even the slightest rotation. The solution to this problem is to further modify the square cross-section, creating a groove to enclose the flange.

December 2023 Update

The Tesserxel engine has created a railway train scene, click here for the link, click here for the tutorial.

Switches

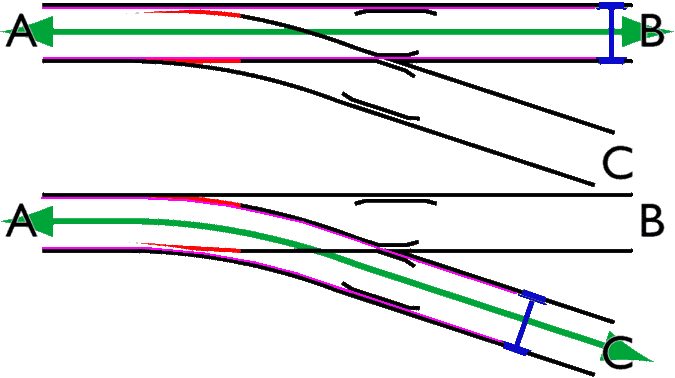

Now let’s talk about switches. Many people might not even understand the switch system of railways in the three-dimensional world. Its principle is simple, and because it’s simple, we have the ability to extend it to four dimensions. Here’s an animated demonstration from Wikipedia:

The core of a switch is guiding the protruding flange. In the diagram below, I’ve colored the areas where the flange passes in pink:

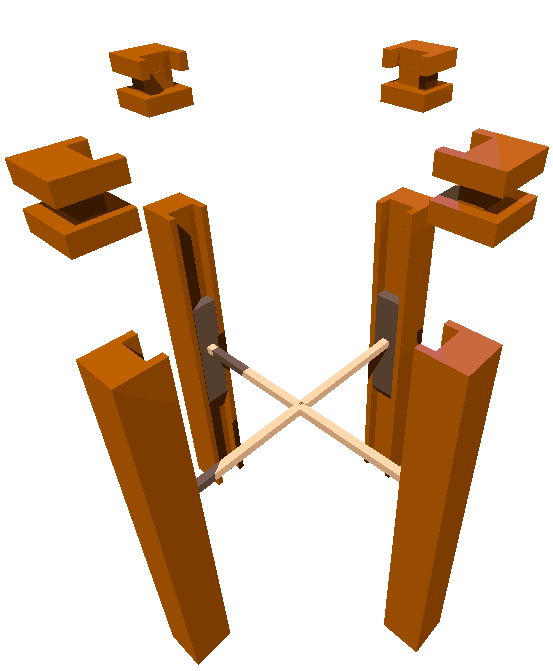

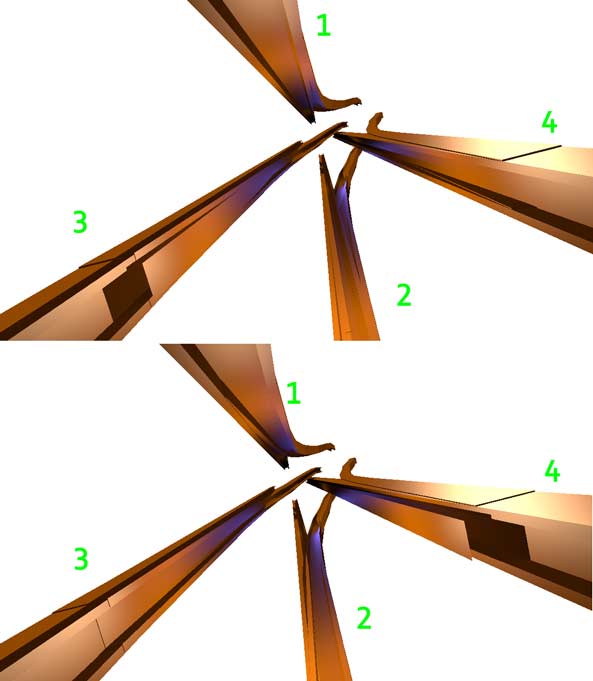

Now it’s our turn to conceive four-dimensional switches: Below is a top view of a switch where the railway branches in the directions of tracks three and four. Since the anti-rotation parts of the tracks protrude, these two parts are made separately when making switches, because tracks one and two only need to move the anti-rotation parts, while tracks three and four only need to move the main track parts.

Well, we’ve finally finished discussing the construction of roads and railways in four-dimensional space.

However, have we really finished?

Below I’ll introduce a special means of transportation in the four-dimensional world that should be popular with people, especially those of us who want to tour four-dimensional space. This idea comes from discussions on this website.

Train-Car/Car-Train

We know that driving four-dimensional cars is very difficult, like flying an airplane - even native four-dimensional beings find learning to drive extremely painful. So having train wheels locked onto tracks means you don’t have to worry about controlling direction. But train transportation is one-dimensional, branching requires switching, and departures need a dispatch system, so you can’t just drive however you want. Now our new means of transportation is about to debut, combining the advantages of both cars and trains - I don’t know what to call it, so let’s temporarily call it a train-car or car-train.

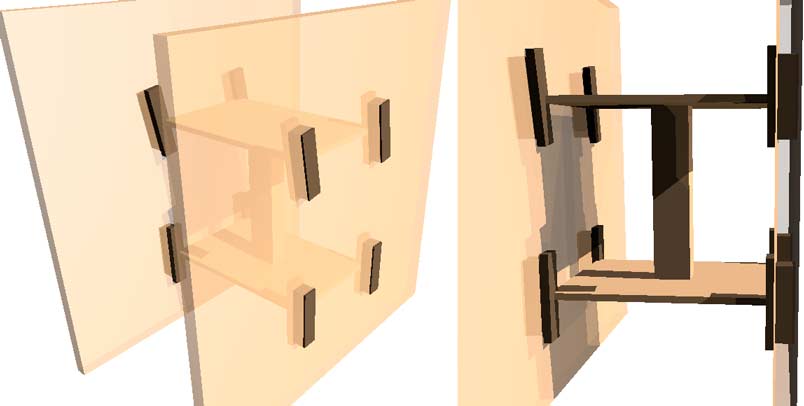

The train-car is a combination of train and car. It travels on two-dimensional tracks and has a steering wheel (the familiar disc, not a sphere!), allowing free steering on the two-dimensional track surface. This is good news for us three-dimensional people (and for four-dimensional women drivers), because driving this vehicle is just like driving our regular three-dimensional cars. Let’s look at the track and wheel design:

The planar track restricts rotation and steering perpendicular to the track, greatly reducing driving difficulty. Of course, what I just showed was a two-dimensional flat track. Curved tracks can not only curve left and right like our roads (requiring manual steering wheel control for such turns), but also curve upward (turning perpendicular to the track direction), or become helical surfaces like twisted paper strips (rotation). Two-dimensional tracks don’t need switch designs either, because people can control the vehicle’s direction to choose branch roads.

December 2023 Update

The Tesserxel engine has created a two-dimensional railway car-train scene, click here for the link, click here for the tutorial.

All our previous discussions have assumed that the three-dimensional ground is flat. However, roads will have upward and downward slopes when leaving the plains, making them even harder to understand without four-dimensional eyes. Let’s end our discussion of transportation here.