5D Cube's Cross-section Puzzle

This article is divided into two parts. The first part is about the puzzle of a 5-dimensional cube’s cross-section, and the second part is an exploration of the properties of a certain type of 4-dimensional polytope. We will be solving a problem in 5D space, but the main discussion will be in 4D space.

part 1

Let’s start with a warm-up problem involving only four dimensions (not five)

We know that a cube can be obliquely sectioned to produce a regular hexagonal cross-section, which intersects all faces of the cube. Generalizing to four dimensions, we want to find an “oblique” cross-cell (a cell refers to a 3D “face,” the same below) that intersects all eight faces (cubic cells) of a hypercube. Of course, there are many ways to make such an “oblique” cut that fits the requirements. We want the most “symmetrical” method, which is to choose a cross-section perpendicular to the main (longest) diagonal and passing through the center of the hypercube. Does this method satisfy the requirement of intersecting all faces? What shape will it be? If the cross-section does not pass through the hypercube’s center, what other shapes might we get?

The answer is that you get a regular octahedron! (Its edge length is $\sqrt 2$, passing through the face diagonals of all squares). If the cross-section does not pass through the center, we can also get shapes like a regular tetrahedron, a truncated tetrahedron, and others.

It seems that a cross-section perpendicular to the main diagonal and passing through the center of a hypercube not only meets the requirement of intersecting all faces but is also the most symmetrical. If we continue and generalize to 5D space, choosing a cross-section (a 4D hyperplane) that is perpendicular to the main diagonal of the 5-dimensional cube and passes through its center, we should get a 4D figure X. We believe this 4D figure X is an analogy that follows this progression: line segment (from an oblique cut of a square) -> regular hexagon -> regular octahedron -> X. Can you describe the basic characteristic parameters of X and roughly draw its stereographic projection?

Finding figure X

The 4D figure X should be a 4D cross-section obtained by slicing a 5-dimensional cube. It intersects the 10 faces of the 5-dimensional cube (i.e., the 10 hypercube “faces”—think about why it has 10 faces). Since there is symmetry, could it be a regular 10-cell? Unfortunately, the regular 10-cell does not exist, because there are only six regular polytopes in 4D space: the 5-, 8-, 16-, 24-, 120-, and 600-cells. We have never heard of a “regular 10-cell.” In fact, the reason we choose a cross-section perpendicular to the main diagonal and passing through the center is that this cross-section has the same “status” (e.g., the same angle, although we haven’t discussed angles in 5D space yet) with respect to all ten 4D faces of the 5-dimensional cube. Therefore, we have reason to believe that the ten cells of the resulting 4D figure X are all congruent. What shape is each cell? It feels like we don’t have a clue.

When we are stuck on a problem in a higher-dimensional space because it’s too abstract, there are generally two solutions: one is to use an algebraic method (for example, to solve the problem of the angle between two planes in 4D space), and the other is to think about the situation in lower dimensions. We will try to avoid the algebraic method for now, as it can be a bit boring. So, let’s think about the 4D case: Consider the series of cross-sections (3D faces) of a 4D cube that are perpendicular to the main diagonal, not necessarily passing through the center. This series of 3D figures has a feature: their 2D faces are all triangles or hexagons. These triangles or hexagons are precisely the series of cross-sections obtained by slicing a cube perpendicular to its main diagonal in the 3D case! The principle is very simple: when we slice a figure in n-dimensional space, its (n-1)-dimensional boundaries are subspaces of the n-dimensional space, and they are also correspondingly sliced. In the series of analogies with the cube, the “sub-cross-section” obtained where the cross-section intersects the (n-1)-dimensional subspace is also perpendicular to the main diagonal of the (n-1)-dimensional cube. To summarize, we have the following information about X:

- X is composed of 10 congruent cells;

- The shape of the cells should be one of the following: a tetrahedron, a truncated tetrahedron, or an octahedron.

It is worth noting here that a cross-section passing through the center of an n-dimensional cube and cutting its (n-1)-dimensional face (an (n-1)-dimensional cube) will not pass through the center of the (n-1)-dimensional cube, because the (n-1)-dimensional face is a distance of half the edge length away from the center of the n-dimensional cube. Therefore, we can rule out the octahedron as the shape of the cells.

Since every 4D face of the 5-dimensional cube has a parallel opposing face, every 3D face of the cross-section X also has a parallel opposing face. This makes us think that we can describe this figure X by “layers,” just like how we describe the 120-cell:

| Position | Number of cells |

|---|---|

| North Pole | 1 |

| Northern Hemisphere | 4 |

| Southern Hemisphere | 4 |

| South Pole | 1 |

Note why I can confidently give 4 for the northern and southern hemispheres: because the shape of X’s cells can only be a tetrahedron or a truncated tetrahedron, the number of cells adjacent to the North Pole must be 4. A truncated tetrahedron has four cells that share a hexagon with the North Pole and four others that share a triangle, and the distances are clearly different. Therefore, the number of cells in the “first layer” outside the North Pole is still 4.

In fact, X’s cells cannot be tetrahedra. If they were tetrahedra, the four outward-facing vertices of the “first layer” of tetrahedra would have a gap between each pair. Filling these gaps would require at least 6 tetrahedra, which is inconsistent with the layered description above. Of course, another case is that the four outward-facing vertices of the “first layer” of tetrahedra are shared, which would make it a regular 5-cell. The symmetry does not allow for other cases, such as sharing only 2 or 3 vertices. Therefore, we have ruled out all possibilities for the cells of X being tetrahedra.

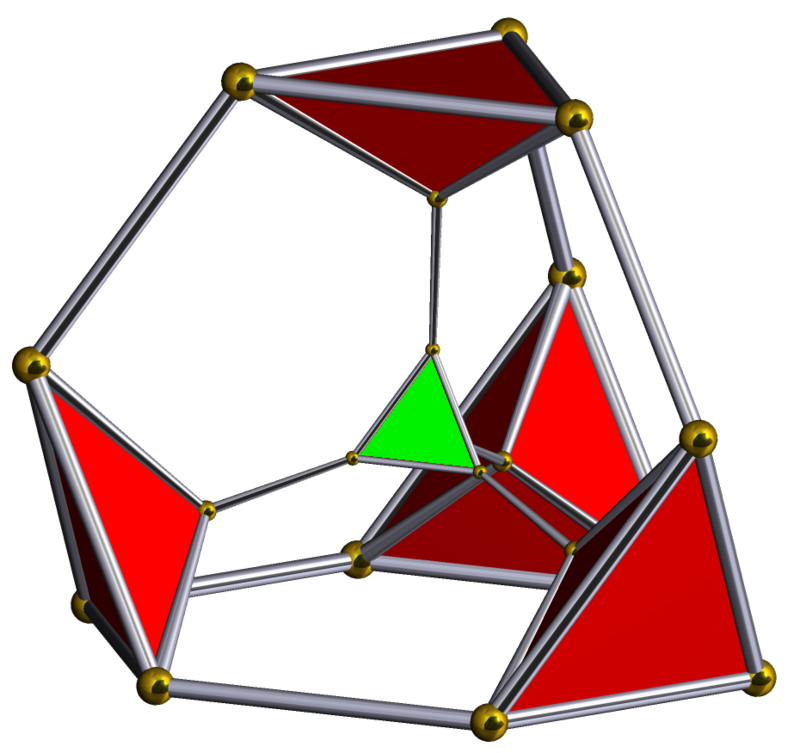

So the last possibility is the answer: a truncated tetrahedron. The “first layer” of truncated tetrahedra outside the North Pole shares a hexagon with the pole and a triangle with the South Pole; the “first layer” of truncated tetrahedra outside the South Pole shares a hexagon with the South Pole and a triangle with the North Pole. The geometric figure X is a bitruncated 5-cell. For details, you can refer to the corresponding English Wikipedia article. This polytope can also be found in the jenn3d software.

part 2

The jenn3d software provides a family of bitruncated polytopes. So, what exactly is bitruncation? Bitruncation is when the truncation process goes too far. However, in 3D space, a bitruncated polyhedron is just a truncated version of the dual of the original polyhedron.

For example, when truncating a cube, we first get the (uniform) truncated cube (the third figure), then the rectified cube (the fifth figure), which is the maximum critical state that can be reached by truncation. Exceeding this state results in a bitruncated cube (the seventh figure). But starting from an octahedron, we first get a (uniform) truncated octahedron (the seventh figure), then the rectified octahedron (the fifth figure, which is also called a cuboctahedron), and then the bitruncated octahedron (the third figure).

We can see that in 3D space, there is no need for the term “bitruncation,” but it’s different in 4D space. Let’s take a look at the entire process of truncating a regular 5-cell.

First, we get a truncated 5-cell. When we truncate to the midpoints of the edges, we get a rectified 5-cell. What shape do we get if we continue truncating past the midpoints?

(The following images are all from the English Wikipedia)

The rectified 5-cell has regular octahedron cells and regular tetrahedron cells. The regular octahedron is a “rectified tetrahedron,” so continuing the truncation process will cause the regular octahedra to revert to truncated tetrahedra, and the regular tetrahedra will also become truncated tetrahedra. Thus, all cells become truncated tetrahedra, which is what the bitruncated 5-cell is.

Not all bitruncated regular polytopes are bounded by only one type of cell. This is only the case for self-dual regular polytopes. Another very beautiful bitruncated regular polytope is the bitruncated 24-cell (the regular 24-cell is self-dual).

Now we can discuss the shapes of cross-sections obtained from a 4D hyperplane perpendicular to the main diagonal of a 5D cube at any position. We can imagine an animation of the cross-section moving: first, we see a regular 5-cell starting as a point and growing, then it gets truncated into a truncated 5-cell, which continues to be truncated into a rectified 5-cell, a bitruncated 5-cell, and then reverts back to a rectified 5-cell, a truncated 5-cell, and finally back to a regular 5-cell, which shrinks and disappears.