4D Space (III): On Regular Polytopes

#This article discusses geometry in pure space, not spacetime in physics! Recommended video “Dimensions: A Walk through Mathematics“ for a preliminary understanding of 4D space

The basic method for studying regular polytopes in 4D space is still analogy: so you probably need to have some understanding of regular polyhedra in our three-dimensional space first (you can refer to Matrix67’s introduction to regular polyhedra).

There are a total of six regular polytopes: simplex (5-cell), tesseract (or hypercube, 8-cell), 16-cell, 24-cell, 120-cell, and 600-cell. The film only shows their projections (parallel projection and stereographic projection) and some basic geometric information. Today, let’s look at how they are specifically constructed. Except for the 24-cell, we can find three-dimensional analogies for the other five regular polytopes—they are the regular tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron, respectively.

Simplex (5-cell)

The first 4D geometric object discussed in the third episode of “Dimensions” is the simplex. Although the analogy in the film is reasonable, we need to know why this analogy is correct—is it just drawing five points and connecting them to get a simplex? For better understanding, let’s start from 0 dimensions:

- 0-dimension—a point (0-simplex);

- 1-dimension: Connect this point with another point outside it to get a line segment (1-simplex);

- 2-dimension: Connect this line segment with a point outside it to get a triangle, where the base of this triangle is the original line segment, and the other two sides are formed by connecting the outside point to the endpoints of the original line segment (2-simplex);

- 3-dimension: Connect this triangle with a point outside it to get a tetrahedron, where the base of this tetrahedron is the original triangle, and the other three faces are formed by connecting the outside point to the three sides of the original triangle to form triangles (3-simplex);

- 4-dimension: Connect this tetrahedron with a point outside it to get a 5-cell, where the base cell of this 5-cell is the original tetrahedron, and the other four cells are formed by connecting the outside point to the four faces of the original tetrahedron to form tetrahedra (4-simplex);

- 5-dimension: Connect this 5-cell with a point outside it to get a “6-supercell”…

- ……

We see that connecting a figure with a point outside it is precisely the way cones are formed. And the n-dimensional simplex is a series of such cones. We can view a triangle as a “line segment cone,” a tetrahedron as a triangular pyramid, a 5-cell as a “tetrahedral cone,” and so on.

Tesseract (8-cell)

There are too many explanations of the tesseract online, and it is the easiest to understand, so I don’t need to explain it again.

16-cell

Strangely, in the “Dimensions” film, after discussing the hypercube, it skipped the 16-cell and went directly to the 24-cell. In fact, the 16-cell is also quite fascinating.

This series of n-dimensional geometric objects is called n-cross. The 16-cell is the 4D analogue of the regular octahedron in three-dimensional space, so we must first clearly understand the regular octahedron. The regular octahedron is the dual polyhedron of the cube—in geometry, if every vertex of one polyhedron can correspond to the center of every face of another polyhedron, it is the dual polyhedron of the other.

The regular octahedron also gives us a more intuitive feeling: it looks like two inverted pyramids (square pyramids). The bases of the two pyramids form a hollow square structure. In fact, we can also find a hollow octahedral structure in the 16-cell! It can be seen as two inverted “octahedral pyramids.” The bottom-left image shows the stereographic projection of the 16-cell with a vertex at the pole, clearly revealing the central octahedral framework.

The stereographic projection of the 16-cell can also be seen as four spheres intersecting pairwise (right image), so it can be used to draw Venn diagrams for 4 sets.

24-cell

This is the narrator’s favorite figure in the “Dimensions” film. The film says it has no three-dimensional analogy, which is actually incorrect. It does have a three-dimensional analogy—the rhombic dodecahedron. Similar to understanding the 16-cell, we must first clearly understand the rhombic dodecahedron.

Perhaps many people have not heard of the rhombic dodecahedron before. Now let’s explain its formation process starting from the most familiar cube.

- A cube has 8 vertices and 6 faces. Imagine pulling outwards from the center of these 6 faces, making each face resemble a square pyramid:

- Continue expanding outwards until two adjacent triangular faces become coplanar, forming a rhombus.

Now let’s observe: The newly formed rhombic dodecahedron has two types of vertices: the original 8 vertices of the cube (3 edges connected to each point) + the 6 vertices “pulled out” from the face centers (4 edges connected to each point). Each rhombic face of the rhombic dodecahedron is formed by two adjacent triangular faces becoming coplanar, so one rhombic face corresponds to one edge of the original cube. The cube has exactly 12 edges, so we also have 12 rhombic faces. The original square edges no longer exist—they have become diagonals within the rhombic faces and are no longer the boundaries of the figure.

Now to four dimensions:

- A hypercube has 16 vertices and 8 cells. Imagine pulling outwards from the center of these 8 cubic cells, making each cell resemble a cubic pyramid:

- Continue expanding outwards until two adjacent square pyramids become coplanar, forming an octahedron (two inverted square pyramids form one).

Now let’s observe: The newly formed polytope has two types of vertices: the original 16 vertices of the hypercube (4 edges connected to each point) + the 8 vertices “pulled out” from the cell centers (4 edges connected to each point). Each octahedral cell of this polytope is formed by two adjacent square pyramids becoming coplanar, so one octahedral cell corresponds to one 2D square face of the original hypercube. The hypercube has exactly 24 2D faces, so we also have 24 octahedral cells. The original 2D faces of the hypercube no longer exist—they have become the hollow square structures inside the octahedral cells and are no longer the boundaries of the figure, but the boundaries of the squares are still the boundaries of the polytope. This is why its projection diagram appears to contain a hypercube—it’s actually just a hollow structure (think of the rhombic dodecahedron).

We see that both types of vertices of the polytope: the original 16 vertices of the hypercube and the 8 vertices “pulled out” from the cell centers, all have 4 edges connected to them. And it can be geometrically proven that the octahedra are regular! So this high-dimensional analogue of the rhombic dodecahedron surprisingly upgraded into a regular polytope, incredible! I understand this “comeback” phenomenon as follows: the body diagonal of the hypercube is an integer 2, which allows the edges of the diagonal geometric figures and the edges along the original coordinate axes to be of equal length, thereby making it possible for all edges to be of equal length.

Densest Packing Problem

There is a very famous class of geometric problems concerning the densest packing of circles or spheres of the same size. The two-dimensional case is as follows:

In three dimensions, there are generally two densest packings: face-centered cubic (FCC) packing and hexagonal close-packed (HCP) packing. Their difference is that the top and bottom layers are either identical or rotated by 180°.

Among these, the frame of the first image (FCC packing) is a cuboctahedron—a cube with its corners truncated until the triangular faces created by truncating adjacent vertices just meet at a point. It is the dual polyhedron of the rhombic dodecahedron. The truncated triangular faces correspond to the 8 square vertices of the rhombic dodecahedron, and the remaining 45° square faces correspond to the 6 vertices pulled out from the face centers of the rhombic dodecahedron. Let’s look at the structure of three-dimensional densest packing: We analyze it as a superposition of three layers: the middle (white) layer of spheres is the densest packing method for circles in a plane, and the three spheres on the top and bottom layers fit perfectly into the six depressions formed by the packing of the central spheres.

The 4D hypersphere densest packing should also consist of three layers: the middle layer being the three-dimensional densest packing. The question is, where should the “upper” and “lower” layers of hyperspheres be filled? We can also try to fill them in the gaps of the upper layer, alternating: here we can fill six triangular prisms formed by the square pairs or six tetrahedra formed by the triangular pairs. However, the tetrahedron seems too small to fill (it’s not that it cannot be filled, but if the hypersphere occupies less space in the lower layer, the space utilization rate will decrease, thus not being the densest packing). So we choose to fill the triangular prisms formed by the square pairs; does the lower layer still need to be filled alternately? No, because filling alternately would require us to fill the lower layer spheres into narrow tetrahedra, which is not what we want to do. Besides, there is no rule that the upper and lower layers must alternate (in the other three-dimensional densest packing, HCP, the upper and lower layers are the same). Therefore, the projected positions of the total 12 hyperspheres in the upper and lower layers coincide, as shown by the 6 blue points in the figure below.

Result: The upper layer has six hyperspheres, forming a regular octahedron, and the lower layer is the same. In the densest packing, one hypersphere is tightly adjacent to a total of 6+12+6=24 spheres! A familiar number! In fact, if we dissect the stereographic projection of the 24-cell, we can find the innermost layer is a cuboctahedron! The regular octahedron inside the cuboctahedron is, of course, formed by those six points in the lower layer, and the upper layer consists of the 6 vertices of the largest, already truncated octahedron on the outermost part.

Using this idea, we provided another analogous explanation for the 24-cell: it is the 4D generalization of the cuboctahedron in three-dimensional space. In fact, this does not contradict the rhombic dodecahedron generalization, because the rhombic dodecahedron is dual to the cuboctahedron, and the 24-cell is self-dual—its number of vertices and cells are both 24! We also presented a distribution of cells for the 24-cell on a hypersphere:

| Position | Number of cells | Description |

|---|---|---|

| North Pole | 1 | Outermost octahedron |

| Northern Hemisphere | 8 | Adjacent to the 8 faces of the North Pole octahedron |

| Equator | 6 | Opposite the 6 vertices of the North/South Pole octahedron |

| Southern Hemisphere | 8 | Adjacent to the 8 faces of the South Pole octahedron |

| South Pole | 1 | Innermost octahedron |

Let’s consider another perspective: is the 24-cell obtained by truncating some figure, similar to the cuboctahedron? Since each cell of the 24-cell is a regular octahedron, if it were a truncated cell, the truncated vertices should have 8 edges connected to them, which is clearly not a hypercube or a 16-cell. So this analogy fails.

The MathWorld website states that the densest packing in five-dimensional space is also analogous in this way. The densest packing in eight-dimensional space is a combination of two face-centered cubic packings. However, the basic structures for densest packing in six and seven-dimensional spaces are cross-sections of the eight-dimensional densest packing method (I previously mistakenly thought the cross-sections were n-cross polytopes; this has been corrected in this article). Some other higher-dimensional spaces have “disordered” densest packings (i.e., hypersphere arrangements without periodic patterns).

120-cell

The narrator’s favorite figure in the “Dimensions” film is the 24-cell, but my favorite is the 120-cell. I once filled a notebook with drawings of the 120-cell’s stereographic projection structure.

Its stereographic projection diagram is a large bubble composed of 119 “bubbles” with twelve faces each. Someone 3D-printed 119 dodecahedra, and it felt like a jigsaw puzzle designed to form a large dodecahedron. What we need to understand now is how these 119 “bubbles” achieve seamless and intricate tiling. Note that we are no longer analysing analogies from pentagon to regular dodecahedron and to 120-cell. The regular dodecahedron’s structure is too complex, so we directly consider it as a pattern of regular dodecahedral tiling on a hypersphere. Given this, let’s look at the distribution of dodecahedra on the hypersphere layer by layer:

| Position | Number of cells | Description |

|---|---|---|

| North Pole | 1 | Outermost dodecahedron |

| Arctic Circle | 12 | Adjacent to the 12 faces of the North Pole dodecahedron |

| Mid-Latitudes | 20 | Fills the depressions corresponding to the 20 vertex positions of the North Pole dodecahedron around the Arctic Circle |

| Tropic of Cancer | 12 | Adjacent to the 12 southward faces of the 12 dodecahedra in the Arctic Circle |

| Equator | 30 | Fills the 30 gaps on the 30 edges corresponding to the North and South Pole dodecahedra |

| Tropic of Capricorn | 12 | Adjacent to the 12 southward faces of the 12 dodecahedra at the Tropic of Cancer |

| Mid-Latitudes | 20 | Fills the depressions corresponding to the 20 vertex positions of the South Pole dodecahedron around the Antarctic Circle |

| Antarctic Circle | 12 | Adjacent to the 12 southward faces of the 12 dodecahedra at the Tropic of Capricorn, and also adjacent to the 12 faces of the South Pole dodecahedron |

| South Pole | 1 | Innermost dodecahedron |

Perhaps there is still confusion about the middle ring of 30 dodecahedra; they are distributed in 30 positions on the edges of the dodecahedra. If we connect the midpoints of all edges of a regular dodecahedron, we get a “rectified icosahedron” (icosidodecahedron), which looks like this: (all images below are from en.wikipedia Icosidodecahedron page)

Among them, you can find many hollow decagonal structures. Its stereographic projection can better reflect these decagons:

How magical! The stereographic projection diagram consists of six circles. I enjoy drawing stereographic projections of various polyhedra freehand. Other projection diagrams I’ve encountered that are circles include the regular octahedron: 3 circles, and the cuboctahedron: 4 circles (how familiar, yes, it’s the figure that appeared when talking about densest packing). In fact, any (semi-)regular polyhedron where a vertex has 4 edges connected to it can be projected as circles. This indicates that within the 30 regular dodecahedra, we can find six end-to-end connected ring structures, with each ring having 10 regular dodecahedra. Therefore, the dihedral angle formed by any two regular dodecahedra is $180° - 360°/10 = 144°$. In fact, the entire 120-cell can be divided into 12 great rings, each with 10 regular dodecahedra connected end-to-end. We will describe these ring structures in detail in the next section, Fibration.

600-cell

The 600-cell is dual to the 120-cell. Where the 120-cell has a cell center, the 600-cell has a vertex with 12 edges connected to it. Where the 600-cell has a tetrahedral cell center, the 120-cell has a vertex with 4 edges connected to it. Therefore, due to duality (vertex-cell, edge-face), the 600-cell has no new structures, so we will not discuss it for now. As for some people saying that the stereographic projection of the 600-cell contains the unfolded diagram of a simplex (5-cell), I believe this is just a coincidental resemblance and they have no actual connection.

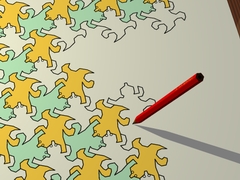

Tessellations

Do you remember the lizards that appeared in the “Dimensions” film? Let’s look closely at the painting with the lizards: the two-dimensional lizards can seamlessly tile the entire two-dimensional space. The original artwork is by Escher (there is an excellent book about him, “Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid”). He was a peculiar artist who specialized in drawing optical illusions and mathematical geometric figures.

This type of close packing of figures is called “Euclidean tessellation.” Of course, what we are most concerned about is regular polygon tessellation:

- In two dimensions, only triangles, squares, and regular hexagons can tessellate.

- In three-dimensional space, only cubes can tessellate. However, if we broaden the scope beyond regular polyhedra, for example, we find that rhombic dodecahedra can densely pack three-dimensional space!

- In 4D space, there are three regular polytope tessellations: the hypercube, the 16-cell, and the 24-cell. However, I haven’t yet imagined how the latter two stack… If you’re interested, you can think about it.

Why is it called “Euclidean tessellation”? Does that mean there are “non-Euclidean tessellations”? “Euclidean” refers to flat space, which has zero curvature. Earlier, we said that we view the 120-cell as a “pattern” on the surface of a hypersphere; this is spherical tessellation, where the sphere has positive curvature (>0). Regular polyhedra can also be seen as two-dimensional spherical tessellations, which is the essence of regular polyhedra and regular polytopes. There is also “hyperbolic tessellation,” which has negative curvature (<0). Hyperbolic tessellations are also quite stunning and are the subject of many of Escher’s representative artworks.