4D Space (V): More Geometries [Part 1]

Duocylinder and Duoprisms

The previous article introduced a new 4D geometric body:$$\begin{cases}x^2+y^2\le a^2 \\ z^2+w^2\le b^2\end{cases}$$It only has two curved three-dimensional faces:$$\begin{cases}x^2+y^2= a^2 \\ z^2+w^2\le b^2\end{cases}、\begin{cases}x^2+y^2\le a^2 \\ z^2+w^2= b^2\end{cases}$$

Their equations look like part of a cylindrical surface; these two three-dimensional faces intersect to form a two-dimensional curved surface, which projects stereographically to that torus (the torus divides three-dimensional space into inner and outer parts, corresponding to its two three-dimensional surfaces).

Even with the equations of the geometric body, we still cannot imagine what it looks like, but we can see from the equations that its projection on the $xy$-plane is a circle with radius $a$, and its projection on the $zw$-plane is a circle with radius $b$. Through calculation, we can obtain the shape of each projection. We can imitate “three views” to draw its “four views” (3D) or “six views” (2D), but understanding a geometric body through three views does not seem to be a very intuitive method, and four views are also not intuitive. I have attached the four views at the end of this article. Instead, I believe the cross-section method is more intuitive. Let’s make this figure pass through three-dimensional space, like in episode 3 of “Dimensions,” and observe its cross-section animation:

|

|

|

I wonder if you’ve noticed that the “stretching and shrinking” of the cross-sections of this cylinder is similar to the animation of a circle passing through a straight line. This indicates that every edge of this cylinder’s lateral surface is a circle in 4D space! This gives us the impression that it is a cylinder with a circular base and circular sides. This geometric body is called a “duocylinder“ in English.

Note that the duocylinder is not the “cubinder” mentioned in our first article. The cross-section animation of a cubinder is very simple: a cylinder suddenly appears, and after a while, it suddenly disappears; the cross-section animation of a duocylinder is a cylinder that first lengthens and then shortens. So, besides the cross-section animation, what is the relationship and difference between a duocylinder and a cubinder? Let’s first look at a new class of geometric bodies: duoprisms. Duoprism is a figure obtained by taking the direct product (Cartesian product) of two polygons.

In the previous article, we introduced the cylindrical surface as the direct product of a line segment and a circle, which can be thought of as being composed of many line segments or many circles (a cylinder is the direct product of a solid disk and a line segment). These two perspectives show that the direct product has a commutative property. Figuratively speaking, a duoprism is a figure formed by continuously translating one figure A within the range of another absolutely perpendicular figure B, filling up all the space (4D) that can be occupied by translation. Of course, many of the lines translated out are inside this space (4D), so we only see the outline of figure A at each vertex of figure B’s edges.

The duocylinder we see is the direct product of two circles, while the cubinder is the direct product of one circle and one rectangle. (Generally, the direct product of an n-dimensional figure and an m-dimensional figure results in an (m+n)-dimensional figure.)

Since a circle is a regular polygon with infinitely many sides, let’s start by discussing the direct product of regular polygons.

n m-gonal Duoprism

If we look closely at the projection of a hypercube, we will find that the squares inside can be divided into two absolutely perpendicular categories (red and blue parts in the lower right image). Not only that, we can also draw the projection of a hypercube in the following order: first draw a blue parallelogram (actually a square, due to perspective), and then “copy” four red parallelograms at each vertex; we then select a red parallelogram and “copy” the remaining three red parallelograms at each vertex.

This drawing method shows that the hypercube resembles a prism with a blue (or red) square base and red (or blue) square generatrices! We now need to broaden our understanding of a concept: the generatrix of a prism does not necessarily have to be a one-dimensional figure (a line); it can be any higher-dimensional figure. Do you remember the strange octagonal prism-prism we constructed in the first article? It was the direct product of an octagon and a triangle:

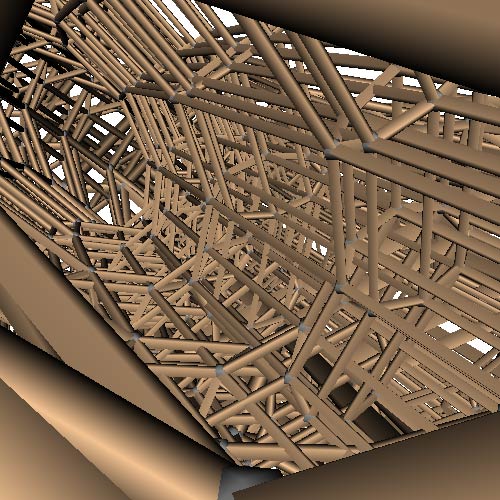

Wikipedia calls the direct product of a regular m-gon and a regular n-gon: m n-gonal prisms. When $m=4$ and $n=\infty$, we get a cubinder. At this point, one of the figures has infinitely many sides, so we would have to translate infinitely many times to draw it! In fact, it has curved cells (analogous to curved surfaces), and we cannot draw the wireframe projection of curved cells because they are composed of countless tiny flat cell micro-elements. Let’s stop at a 16-gon. The left image below shows the projection of a 16-4-gonal duoprism from two perspectives. We see that the first perspective is indeed very similar to a cubinder; it is a strip made of 4 circles, with squares connecting their corresponding points. In the second perspective, it feels like a strip made of 16 squares, with four circles connecting the corresponding points of the squares. This is again the commutative property of the direct product.

If we replace the square with a pentagon, … a 16-gon, we can see that these two perspectives become increasingly similar. For a 16-16-gonal duoprism, the two figures become identical.

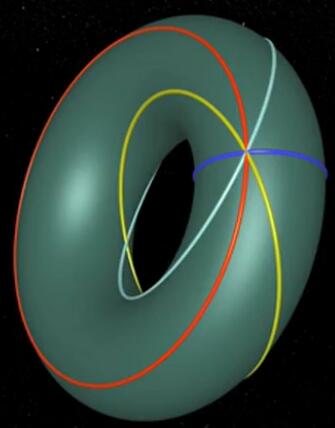

After looking at parallel projections, we can also look at the stereographic projection of a duoprism. A 16-16-gonal duoprism already closely resembles the torus in a fiber bundle. Due to the commutative property of the direct product, we can finally understand why the longitude and latitude lines on a torus are interchangeable. (These models are available in jenn3d under the “duoprisms” menu.)

All 4D Analogies of Cylinders

It’s time to summarize the concept of “prisms.” Our three-dimensional prism is the direct product of a 2-dimensional base $S$ and a line segment $h$. In four dimensions, the traditional prism is the direct product of a 3-dimensional base $V$ and a line segment $H$. Then “xx-prismatic prsim” is $V\times H = S\times h \times H$$=S\times (h \times H)=S\times (\text{rectangle})$. Therefore, there are four types of 4D cylinder analogues:

- Spherinder (3-sphere $\times$ 1-sphere);

- Duocylinder (2-sphere $\times$ 2-sphere);

- Cubinder (2-sphere $\times$ 1-sphere $\times$ 1-sphere);

Rotations in 4D Space

The torus in stereographic projection is merely a three-dimensional “shadow.” We see that its actual entity, the duocylinder, is a convex cell with no holes. Let’s return to the definition of a three-dimensional torus: it is formed by rotating a circle around an axis in the plane of the circle.

Rotations in 4D space are complex. But here we only need an analogy: a 4D “spheritorus” is formed by rotating a sphere around a plane in the three-dimensional space containing the sphere – this is a 4D solid of revolution.

What does it mean to rotate around a plane? In the case of “simple rotation,” we can find a plane where all points remain stationary during the rotation (similar to a 3D axis of rotation). In fact, the trajectory of any point’s rotation in an n-dimensional space is a circle, and all these circular trajectories should lie in parallel planes, whose centers form that plane.

For example, if you take the $x$ and $y$ coordinates of a 4D object $(x,y,z,w)$ and rotate them around the origin, then the $xy$-plane is the plane of rotation, and points on the $zw$-plane do not move. We say this is a rotation about the $zw$-plane.

Since there is single rotation, we also have double rotation! Still with the 4D object $(x,y,z,w)$, we let the $x,y$ coordinates rotate at a uniform speed $v_1$, and the $z,w$ coordinates rotate at a uniform speed $v_2$. Since they are absolutely perpendicular, their movements do not interfere with each other, resulting in the entire space rotating. Except for the origin, you can no longer find any axes or planes that are stationary! Points not on the coordinate planes will participate in the superposition of the two rotations, which explains the complexity of 4D space rotation.

If the $x,y$ coordinates and $z,w$ coordinates rotate at the same speed, the trajectories of all points are still circles. We can imagine that this rotation will fill the entire 4D space with circular orbits. If we only consider the circular orbits on a unit hypersphere and project them stereographically, we get the Hopf fibration!

If the $x,y$ coordinates and $z,w$ coordinates rotate at different speeds, this is the composition of two unrelated circular motions. CFY’s article has detailed textual and graphical explanations.

Double rotations, like fiber bundles, have chirality. Let’s use a diagram to illustrate the relationship of these rotations: four sets of circles on a torus.

A rotation around the $xy$-plane corresponds to the blue circle, a rotation around the $zw$-plane corresponds to the red circle, a right-handed isometric rotation corresponds to the yellow circle, and a left-handed isometric rotation corresponds to the white circle. Why do the yellow and white circles intersect? Their intersection represents the $zw$-plane and $xy$-plane both rotating 180°, which is the “central reflection transformation” in 4D space—a transformation that maps any point to a point symmetric with respect to an origin! (Three-dimensional and other odd-dimensional spaces cannot achieve central reflection transformation through rotation, because a mirror image is obtained after central reflection transformation, but 4D and other even-dimensional spaces can achieve it through rotation.)

What about non-isometric rotations? Their rotation trajectories form some knots! Since these rotation trajectories are on the surface of a torus, these knots are called torus knots. See CFY’s article for images.

Why can circles on a torus (note that this circle is not the intersection circle of the rotation plane and the hypersphere, because the longitude and latitude lines of the torus are not part of the Hopf fibration) correspond to rotations? We know that a torus is originally a stereographic projection of a duocylinder, and it can be described by parametric equations of circles on the $xy$-plane and $zw$-plane: two angles respectively on the $xy$-plane and $zw$-plane. Of course, it can and can only represent rotations occurring on the $xy$-plane and $zw$-plane; rotations on the $xz$-plane of this torus cannot be drawn.

Rotations in 4D space can also be explained algebraically, and many of their properties can be derived. We will discuss this later.

Spheritorus

Let’s return to the torus analogy. A spheritorus certainly has holes like a torus, so it’s not a convex polytope. Stereographic projection is not suitable for curved cells, and wireframe projection is also unrealistic. To understand the geometry, only the cross-section method remains. Let’s first look at the cross-section animation of a three-dimensional torus parallel to its axis of rotation:

By analogy, please think about what the cross-section animation of a 4D spheritorus parallel to its plane of rotation would look like. I will provide the answer below.

Cross-section animations can fully display any complex three-dimensional/4D geometric body. Therefore, it stands to reason that by observing the cross-section animation of an object in one direction, we can infer the cross-section animation in another direction. Now let’s slice the three-dimensional torus from another direction—a plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation: can you infer the cross-section animation in another direction below directly from the above cross-section animation without thinking about the three-dimensional appearance of the torus?

By analogy, please think about what the cross-section animation of a 4D spheritorus perpendicular to its plane of rotation would look like.

Answer revealed below:

Fortunately, we have computers that can draw these cross-sections:

This figure is almost a three-dimensional replica of the two-dimensional cross-section shapes obtained by slicing a three-dimensional torus with a plane.

Observing it, we conclude: a figure obtained by rotating a two-dimensional cross-section around a horizontal axis. Two-dimensional: a circle grows, splits into two circles, and then merges back. Three-dimensional: a sphere grows, splits into two spheres, and then merges back. Doesn’t it resemble cell division?

From another perspective

We can change the perspective—slicing the 4D spheritorus with a cell (hyperplane) perpendicular to the plane of rotation:

Hmm, we’ve figured out the cross-section animation of the spheritorus. Do you remember that slicing a torus diagonally can produce two Hopf circles? But a spheritorus doesn’t seem to be able to be cut into two spheres. I can only find this figure:  It no longer corresponds to the solid of revolution of the torus cross-section; it feels like forcefully inflating the cross-section into a three-dimensional figure.

It no longer corresponds to the solid of revolution of the torus cross-section; it feels like forcefully inflating the cross-section into a three-dimensional figure.

Another Analogy of the Torus – Torisphere

Why are the analogies of the torus always “sphere” or “something rotating,” and not a torus rotating around a plane to form a “toric torus”? While this idea might seem pedantic, let’s take a look below:

A torus is not as highly symmetrical as a sphere, so there are many ways to choose the plane around which it rotates:

- Choose a plane perpendicular to the torus’s axis of symmetry (Called Tiger, or Duotorus).

- Choose a plane parallel to the torus’s axis of symmetry (Ditorus).

- Choose an oblique plane.

We will directly provide the shapes of some of their cross-sections: we can all observe the “shadow” of the three-dimensional torus cross-section.

- Taking a plane perpendicular to the axis

- Direction 1:

- Direction 2: Same as Direction 1! But it’s just like the six faces of a cuboid, similar in shape but possibly different in size, depending on the specific parameters of the ditorus. This indicates that the torus obtained by rotating parallel to the axis has good symmetry. In fact, this symmetry is the same as that of a duocylinder! Because when this torus is infinitely thin (becoming a circle) and rotated, it transforms into that toroidal surface—the intersection surface of the two curved cells of the duocylinder!

- Taking a plane parallel to the axis

- Direction 1:

Imagine if the plane parallel to the axis happens to pass through the torus’s axis of symmetry, the resulting geometric body would be the torisphere mentioned earlier. (Imagine a circle rotating around an axis can produce either a sphere or a torus). - Direction 2: A toroidal surface first thickens then thins. (Like a toroidal pipe, image omitted).

- Taking an oblique plane

- Direction 1: The three images on the lower right are too bizarre. Fortunately, we have computers, otherwise I couldn’t imagine them.

- Direction 2: Lower left image, one large and one small torus, relatively regular.

Appendix: Four Views of the Duocylinder