4D Space (X): Knots and Links

This time we’ll look at an interesting topic: knots in four-dimensional space. Perhaps everyone should already know that due to the extra degree of freedom, all knots in three-dimensional space can be easily untangled in four-dimensional space, so knots are unique products of three-dimensional space. There are no knotting phenomena in four-dimensional space. End of article.

Of course I wouldn’t end this article like that. Although one-dimensional curves cannot form knots, two-dimensional surfaces (two-dimensional ropes?) can form knots! I’ve long heard about four-dimensional knots, but never found specific examples. Claims about Klein bottles are actually incorrect: Klein bottles are non-orientable surfaces. If two-dimensional beings lived on them, they would find themselves “mirrored” after traveling around the bottle once, which could never happen on a sphere. So these two things are fundamentally different (not homeomorphic), like tori and spheres.

Table of Contents:

- Video Recommendation: Knot in 4D

- Various Types of Holes

- Holes Inside Circles

- Holes Inside Spheres

- Two Linked Spheres?

- Holes Inside (Flat) Tori

- Two Linked Bitori?

Let’s first clarify what “knotting” means. I don’t want to use mathematical language (terms like homotopy), but simply put: going from an unknotted state A to a knotted state B is impossible without allowing self-intersections, but becomes possible once self-intersections are allowed (like tearing certain places). Moreover, these self-intersections must be locally “smooth” - generally, if given one more dimensional direction, such self-intersections can be avoided.

Video Recommendation: Knot in 4D

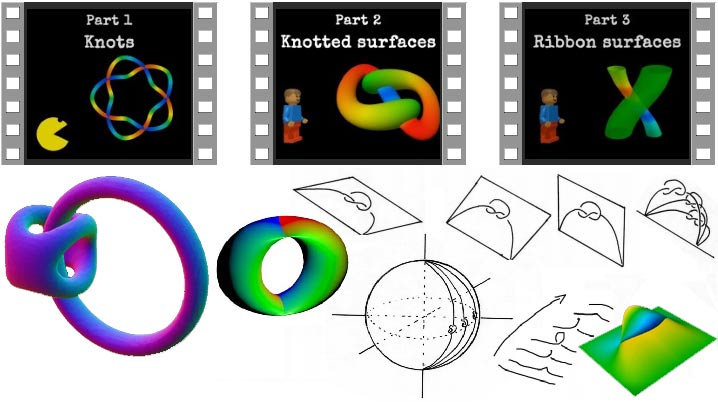

There’s a three-episode video series on YouTube that explains knots in four-dimensional space in detail. I’ve put it on Baidu Cloud, and here’s the author’s official website which contains two interesting Java demonstration programs. Unfortunately, the videos don’t have Chinese subtitles, and the narrator’s English is quite poor (seems to be Italian). I’ll roughly summarize the video content here.

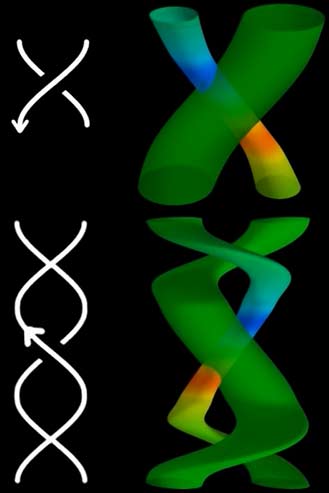

Episode 1: Three-Dimensional Knots

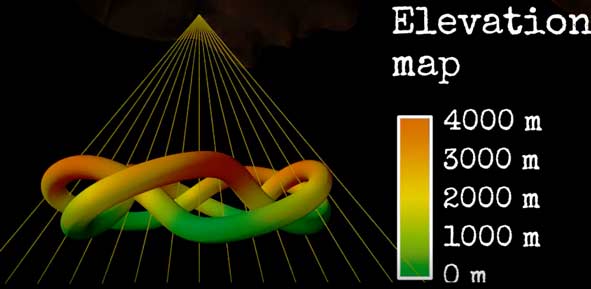

First, in mathematics, a knotted line doesn’t count as a knot because the ends can slide and the knot comes undone. So we connect the two ends after knotting to form a loop, which can’t be untangled no matter how much we pull. How do we represent a knot in three-dimensional space? Through projection, of course. But we must note that during projection, originally non-intersecting lines will overlap at certain points. To show which is above and which is below, we have two representation methods: one is to draw the lower line as broken, the other is to color the entire knot like a topographic map. We’ll also use these methods to represent knots in four-dimensional space.

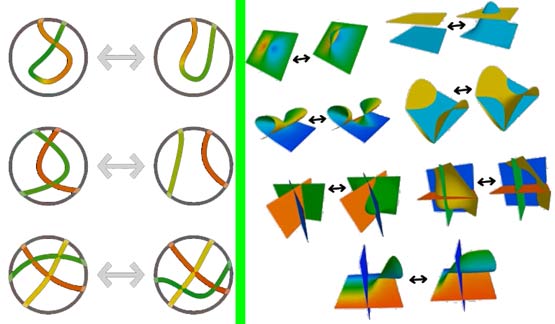

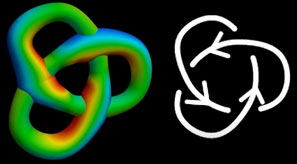

The central problem of knot theory is determining whether two given knots are equivalent. For example, proving that the simplest trefoil knot and an unknotted circle (we also consider a circle as a knot, though trivial and uninteresting) are equivalent is simple - you just need to demonstrate the transformation steps. Mathematician Reidemeister summarized all legal transformation methods in projections, called Reidemeister moves. But proving two knots are not equivalent is difficult. Although from life experience we know it’s impossible to restore a trefoil knot to a circle without scissors, we cannot prove this is impossible even after infinite steps. The video introduces a method of coloring line segments in projections to distinguish different knots by counting coloring methods, since the number of coloring methods doesn’t change under all legal transformations, making it an “invariant” of knots - equivalent knots must have the same number of colorings.

Episode 2: Four-Dimensional Knots

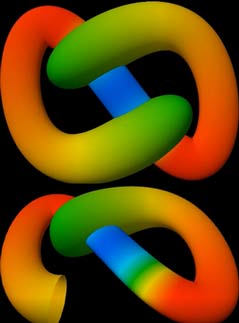

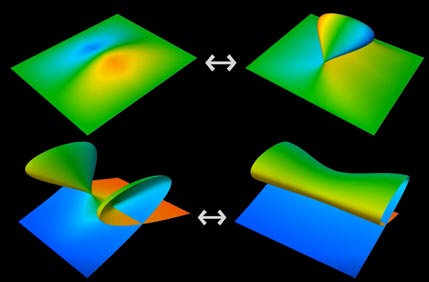

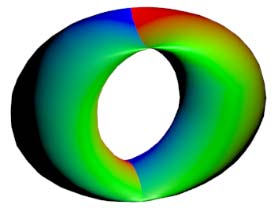

Imagine we take a rectangular cloth and somehow twist it into a knot. But we can just reverse the action to potentially unknot it. So the mathematical approach is to twist the boundary together after knotting, forming a sphere to prevent slipping. What does twisting the boundary together mean? Why not glue opposite edges of the rectangle to form a torus like a donut? Actually, both work! You can see the diversity of four-dimensional knots: tori have holes and obviously can never be equivalent to spheres even allowing self-intersections, so even trivial knots have many possibilities. (There are also two-holed surfaces, Klein bottles, projective planes, etc.) Let’s first look at spherical knots. The video gives a non-trivial knot by stretching a sphere into noodles threading through itself. Through height maps we see the sphere surface has different colors (fourth-dimensional heights) when crossing through itself. When trying to unknot, the green parts in the middle would collide and can’t pass through. Because overlapping parts in three-dimensional projection doesn’t mean fourth-dimensional overlap, but if colors are also the same, then they truly intersect in four-dimensional space. In five-dimensional space, all these two-dimensional knots can be easily unknotted (because even if fourth-dimensional colors are the same, there’s still a fifth direction to avoid collision). Similarly, mathematicians have summarized all legal transformation methods, and the video uses an upgraded coloring method count to prove this knot is not equivalent to a sphere.

The video gives a non-trivial knot by stretching a sphere into noodles threading through itself. Through height maps we see the sphere surface has different colors (fourth-dimensional heights) when crossing through itself. When trying to unknot, the green parts in the middle would collide and can’t pass through. Because overlapping parts in three-dimensional projection doesn’t mean fourth-dimensional overlap, but if colors are also the same, then they truly intersect in four-dimensional space. In five-dimensional space, all these two-dimensional knots can be easily unknotted (because even if fourth-dimensional colors are the same, there’s still a fifth direction to avoid collision). Similarly, mathematicians have summarized all legal transformation methods, and the video uses an upgraded coloring method count to prove this knot is not equivalent to a sphere.

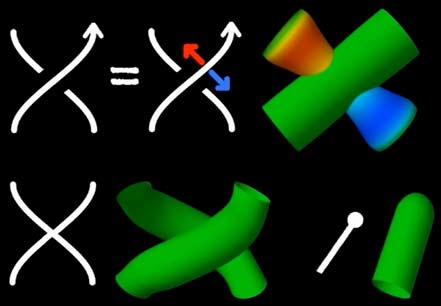

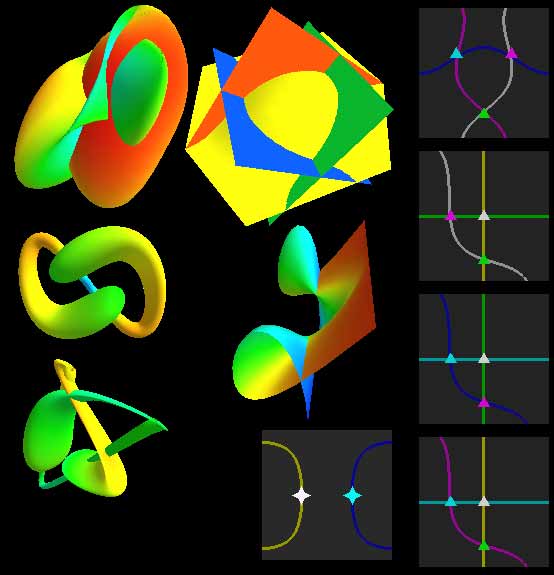

Many legal transformations can be obviously analogized from three dimensions, but there are two less obvious ones involving branch points in projections:

We use cross-section methods to show what these two moves actually do:

Their cross-sectional changes correspond to legal movements of a line in three-dimensional space! (We can even guess these two transformation processes correspond to cross-sectional animations of legal movements of three-dimensional cell projections in four-dimensional space projected into five-dimensional space)

Episode 3: Tube Knots

This mainly discusses special spherical knots that look like tubes and their linear representation method. This representation is like a double projection. Note that order matters only when tubes thread through themselves, while crossing order in three-dimensional space can be changed in the fourth dimension, so we don’t need to show which is above or below.

We can make the crossing directions on one line consistent through some transformations, allowing us to omit arrows at crossings.

The only thing I can’t understand is the legal move shown in the upper left: I can’t imagine how a tube threading through itself unknots - perhaps we should find inspiration from Klein bottle projections?

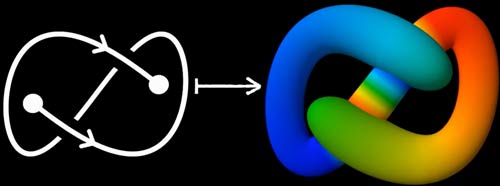

Initially I wasn’t particularly interested in this content, but later I discovered that all three-dimensional knots can be mapped to four-dimensional tube knots through these diagrams, giving four-dimensional beings ideas for textile threads that don’t fall apart! Textile threads are hollow tubes that can’t simply cross over each other like in three-dimensional space during weaving, but must thread through the inside of tubes, just like the spherical knots we saw in episode two.

Finally, the video mentions this representation method covers too few knots - for example, it can’t represent cases where three surfaces intersect at one point in projection. The video briefly mentions there are many complex four-dimensional knots, but mathematicians currently know little about them.

Various Types of Holes

After seeing various knots, let’s look at something different: necklaces made of four-dimensional beads. Following convention, let’s first analyze three-dimensional necklaces: three-dimensional necklace beads are spherical, and they can be strung together because each bead has a hole just big enough for thread to pass through. Can we drill holes in four-dimensional hyperspherical beads to string them together? Of course. Not only is this possible, we can prove that after tying the thread ends together, the hypersphere won’t fall off. This proof uses the four-dimensional knot projection coloring method mentioned in the video. However, we first need to know what the three-dimensional projection of a hypersphere with a hole looks like. Before explaining this, let’s look at various other types of holes in four-dimensional space.

Holes Inside Circles

The most common link in three-dimensional space is the basic component of chains, called the Hopf link (yes! It’s from the linked circles in Hopf fiber bundles). But do one-dimensional objects still exist in three-dimensional space? Actually, real rings have thickness. From this perspective, it’s really two tori linked together. (Could this also count as surface knotting in three-dimensional space?) Our question is whether four-dimensional space has similar things. First, directly taking chains to four dimensions makes them fall apart, for the same reason that four-dimensional space has no one-dimensional knots. All objects in four dimensions have some four-dimensional thickness. One-dimensional circles thickened become ball rings (which we discussed in the previous article), so two ball rings strung together will also slip apart, or in other words, threading from holes in circles (ball rings) will fall off. We can understand this as the hole’s dimension being larger than the thread’s dimension, so it can’t be threaded. This description might be abstract - are there lower-dimensional examples for intuitive understanding?

Imagine a fixed point in three-dimensional space. If a glass ball has a small bubble (zero-dimensional hole) that just encloses the fixed point, then the ball is “tied” to the point and can’t be pulled away. If the glass ball has a normal one-dimensional hole, even if the fixed point is inside the hole, we can just move the ball in the direction the hole penetrates to remove it. Before imagining two-dimensional holes, we need to clarify what a “hole” is. We define: an $n$-dimensional straight hole ($n<N$) in an $N$-dimensional solid figure is the figure obtained by removing an $n$-dimensional flat subspace plus some thickness from the $N$-dimensional solid. For example, a bubble in the center of a sphere corresponds to removing a thickened point, and a holed sphere corresponds to removing a thickened line.

Next, try opening a two-dimensional hole in a sphere surface: a two-dimensional surface is like a knife that directly cuts the sphere in half! The resulting figure becomes disconnected and meaningless, so we won’t discuss this further. Of course, these operations create “sharp” surroundings around holes. Our goal is to find typical smooth equivalent geometric bodies.

These are all the various dimensional holes in three-dimensional space. Now for four dimensions:

- Zero-dimensional holes are still like hollow bubbles;

- One-dimensional holes are penetrating lines that can be threaded on lines but can’t enclose zero-dimensional points;

- Two-dimensional holes are penetrating planes that can be threaded on planes but can’t enclose lines and easily slide off;

- Three-dimensional holes are penetrating cells that divide the four-dimensional figure into two disconnected parts.

Something strange in our analogy: using a two-dimensional blade to cut four-dimensional objects doesn’t actually cut them apart! Because extra dimensions allow parts that should be separated in three-dimensional space to stay connected! Think of similar tragic experiences of two-dimensional beings: they don’t have penetrating food pipes because food pipes would split them in two. They can cut two-dimensional objects with one-dimensional blades, but not in three-dimensional space. Rather than cutting three-dimensional objects with one-dimensional blades, it’s more like poking three-dimensional objects with one-dimensional wire, at most creating holes. So in four-dimensional space, our two-dimensional cutting tools are at most two-dimensional “wires.”

The next task is finding typical figures with various dimensional holes. How? We just need to classify holes in various figures we’ve encountered to determine whether they can be threaded on $n$-dimensional “threads.” First, convex polyhedra, spheres, convex polytopes, and hyperspheres all have no holes. In three-dimensional space, things with one-dimensional holes include tori, and their higher-dimensional analogs include ball rings, ring-spheres, torus rings, and bitori - these names all sound like they have holes. Let’s first look at the hole dimensions of circles thickened in different dimensions. Thickening a circle in two-dimensional space creates a two-dimensional torus with a hole completely inside the figure that can shrink to a point - a zero-dimensional hole. Thickening a circle in three-dimensional space creates a three-dimensional torus with a hole penetrating up and down - a one-dimensional hole.

We see that hole dimension relates to some degree of freedom: suppose the circle lies in the $xy$ plane and we’re at the circle center. Walking along $x$ and $y$ axes hits the circle, but walking along the z-axis has no obstacles. So thickening a circle in three-dimensional space creates an object with a one-dimensional hole. Similarly, if space is four-dimensional, walking along both z and w axes encounters no obstacles - this is a two-dimensional hole, and the corresponding thickened body is a ball ring. We can clearly mark the hole direction but can only visualize them through cross-sectional animations (note that stereographic projection only suits visualizing convex figures without holes).

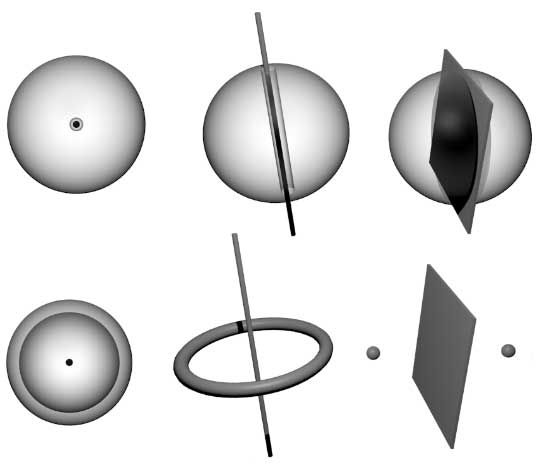

Holes Inside Spheres

Now we finally understand why threading through ball ring holes causes things to fall off - because ball rings’ two-dimensional holes can’t fix one-dimensional threads. To summarize: circles in $N$-dimensional space occupy two dimensions, leaving $N-2$ dimensions as the hole dimension of the circle’s thickened body. If we still want one-dimensional holed figures that can be strung with thread, we need thickened bodies where walking in three directions from the center hits “walls,” leaving only the fourth direction open. This corresponds to thickening spheres - ring-spheres. Comparing central cross-sections, we can see that ball rings indeed have larger hole freedom than ring-spheres.

Finally, let’s organize ball rings and ring-spheres:

- Ball rings are “thick” closed one-dimensional figures (circles) with two-dimensional holes;

- Ring-spheres are “thick” closed two-dimensional figures (spheres) with one-dimensional holes;

We finally found something that can be strung with thread - ball rings, while real threads also have thickness. But like analyzing knots, although ropes have thickness, we can ignore it. Ball rings become one-dimensional circles, ring-spheres become two-dimensional spheres. This simplifies analysis. We no longer distinguish thickened bodies from zero-thickness objects. Restating: two-dimensional spheres can be strung on one-dimensional circles because two-dimensional sphere holes are one-dimensional, matching one-dimensional circles. From another angle, one-dimensional circles can be strung on two-dimensional spheres because one-dimensional circle holes are two-dimensional, matching two-dimensional spheres. In summary, when two objects link, their dimensions and hole dimensions match each other, and it seems $n$-dimensional figure holes are $N-n-1$ dimensional. This conclusion doesn’t actually hold - we’ll see later that two two-dimensional surfaces can also link in four-dimensional space.

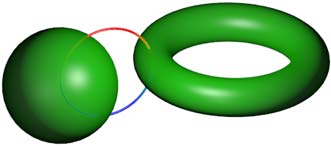

Two Linked Spheres?

Another natural question is whether two spheres can link. If spheres are rigid, then no, because hole dimensions can’t match. But we’ve seen spheres can knot themselves, so two “soft” spheres can definitely link (requiring each sphere itself unknotted).

Similarly, three-dimensional space has a special construction: three linked circles (Borromean rings) where no two are linked but all three together are linked. What about three spheres?

I constructed one solution, but unfortunately can’t prove they’re actually linked because calculating coloring method numbers gives the same result as three separate spheres. Of course, this doesn’t prove equivalence to three separate spheres - other criteria need verification.

Holes Inside (Flat) Tori

Four-dimensional holed objects also include torus rings and bitori. As rotational bodies of already-holed tori, we guess these figures might have two holes. As thickened bodies, they correspond to four-dimensional flat tori and three-dimensional tire-shaped tori.

Let’s first analyze torus holes: First, tori already have holes corresponding to thickened circles - these holes come from circles being hollow. In four-dimensional space, this becomes two-dimensional, fitting planes. Then we take only the torus surface, creating a torus surface - this operation is another hollowing. This hole also has two degrees of freedom. Imagine you’re in a ring-shaped tube - you can walk along the tube or go in the fourth dimension to completely leave the tube, as long as you don’t walk in the remaining two directions of the tube wall. This hole can fit a cylindrical surface (height direction perpendicular to the torus surface’s three-dimensional cell). We see that hole shapes in four-dimensional space are becoming complex.

Actually, four-dimensional flat torus holes are relatively simple: flat tori are Cartesian products of two hollow circles. If we place the two circles in $xy$ and $zw$ planes with centers at the origin, then planes $xy$ and $zw$ won’t intersect the flat torus. This can be derived from the flat torus equation: for example, points on flat tori can’t have both xy coordinates zero.

$$

\begin{cases}x^2+y^2= r_1^2 \ z^2+w^2= r_2^2\end{cases}

$$

Geometrically: hollow circles in planes can be seen as having zero-dimensional holes. Taking the Cartesian product with another two-dimensional figure means continuously translating this figure on another figure. These translation degrees of freedom are two-dimensional, naturally upgrading hole dimension to two. By Cartesian product commutativity, the same applies to the other figure, giving flat tori two absolutely perpendicular two-dimensional holes. Thickening gives bitori, which topologically correspond to poking a hypersphere with two absolutely perpendicular two-dimensional knives.

We really see a structure similar to being stabbed twice by perpendicular lines in the central oblique cross-section of three-dimensional space! This is the Tiger cage mentioned in the previous article.

Finally, the most amazing thing is that flat tori can be turned into regular tori in four-dimensional space, and corresponding holes can also continuously deform. Can we continuously deform cylinders into planes? This is impossible - something must be wrong! Actually, looking at similar situations in three-dimensional space clarifies everything without contradiction.

Two Linked Bitori?

The final question is whether rigid bitori can link with themselves. I only found two unequally sized linked bitori. The principle is that one bitorus’s two-dimensional hole fits on another flat torus surface (thickened becomes bitorus) achieving dimension matching. But if two bitori are the same size, they can’t fit, so it’s very possible that two congruent rigid bitori have no linking solutions.

What does flat torus three-dimensional projection look like? It inevitably produces self-intersections (four branch points, two double intersection lines).

Our two bitori project as:

But through surface legal movement methods mentioned in the video, the large torus can easily become a standard tire-shaped torus. Due to the small torus being threaded on the large torus, we must be careful about self-intersections during movements. The small torus can also become a standard torus through deformation, so the two linked flat tori above are equivalent to two linked torus surfaces. We said this linking is two-dimensional holes matching on two-dimensional surfaces, so we don’t need to care about the rest of the large torus and can directly represent the large torus locally with a plane. I initially thought it was equivalent to the following tube knot diagram:

But tube knots aren’t universal at all - this knot can’t be drawn with corresponding tube knot diagrams. We can see from projections that the entire small torus lies flat threading through the large torus surface, not matching the diagram above. We can think of converting bitori to tori as changing holes from planes to cylinders. For a simpler example: sphere-torus linking can be thought of as spheres matching torus two-dimensional holes (cylindrical surfaces), but how the torus’s one-dimensional hole matches the sphere is very abstract, because spheres span across torus holes, not simply corresponding to dimension matching. Tube knots can’t represent this spanning. Understanding this linking requires rotational body thinking, which we’ll discuss later. Opening a hole in the sphere to make a torus (opening holes where they don’t intersect other projections, so they don’t participate in knotting) is equivalent to the flat torus linking we just discussed, so these two knots are essentially the same.

Four-dimensional space has many hole shapes - actually three-dimensional space does too. But the classification theorem for two-dimensional surfaces tells us all oriented closed surfaces (excluding monsters like Klein bottles) are equivalent to figures with N holes, though this is purely from a homeomorphic mapping perspective. If we bend a hole inside an object into a knot, this hole is definitely not equivalent to an unknotted hole, but this is in the homotopic sense (homotopy emphasizes that deformation processes can’t self-intersect - imagine if self-intersection were allowed, knots would unknot). Is there a classification theorem for three-dimensional cells (using more standard terminology: three-dimensional manifolds)? This problem is too complex. But we said earlier that ball ring and ring-sphere three-dimensional surfaces are equivalent, so maybe one parameter (hole number or Euler characteristic?) could represent them. Three-dimensional space surfaces with two perpendicular intersecting holes are equivalent to four-holed figures. So I strongly suspect that cells with two parallel two-dimensional holes and cells with two-dimensional holes intersecting at points (like absolutely perpendicular intersection at one point) are not equivalent. The two holes in bitori very likely can’t transform into other separated holes.

Rotational Knots

Now let’s discuss other knots. There’s a simplest method for constructing two-dimensional knots: imagine a square paper in the $xy$ plane, knot edge $x$ in $xzw$ space without affecting the $y$ axis, creating a cylinder with the knot in $xzw$ space as base and height parallel to the $y$ axis. This knot construction method is called cylindrical dimension raising. Besides cylindrical raising, there’s rotational raising.

We know spheres are created by rotating semicircular lines. What happens if we put a knot on the semicircular line and then rotate? It seems three-dimensional space can do this! Did we discover three-dimensional sphere knots? Where’s the problem? The problem is that knots are three-dimensional, and during rotation, points that were only overlapping in projection actually coincide, creating self-intersecting surfaces. Four-dimensional space can avoid this: if the knotted semicircle is in space xyz, rotating around the z-axis in three-dimensional space becomes rotating around the zw surface in four dimensions. We analyzed this would cause self-intersection, so instead rotate around the yz plane. Now the direction the knot sweeps is perpendicular to the knot’s own space, eliminating intersections. Someone proved this surface is also knotted. But topologically it’s still a sphere: imagine allowing self-intersections, we could unknot the knot, and the corresponding rotational surface would also self-intersect then unknot into a sphere.

If we call rotating knots revolution, then knots can also rotate during revolution, creating more complex knots with additional “spin.” For deeper understanding, refer to this paper.

Incidentally, the video author’s Java applets have models of rotational knots and knots with additional “spin,” plus another applet visualizing all allowed surface movements and marking overlapping projection positions on each surface.

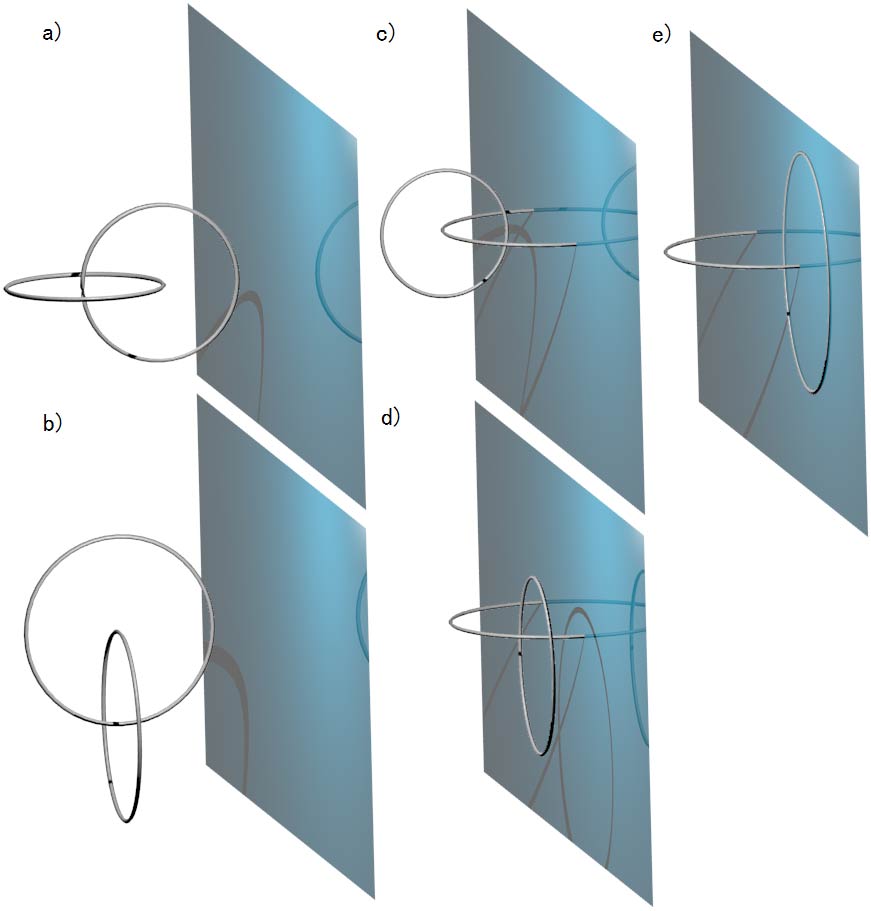

With experience from rotational knots, let’s try rotating three-dimensional space chains to see if we can create new linking methods. Just choose plane rotation in the chain’s space to avoid self-intersections. For example:

We get respectively:

a) One large, one small linked torus surfaces;

b) Flat torus surface and torus surface linked;

c) Torus surface and sphere linked;

d) Flat torus surface and sphere linked;

I saw cross-sectional animations on this website:

e) Circle and sphere linked (the ball ring-ring sphere link we first saw);

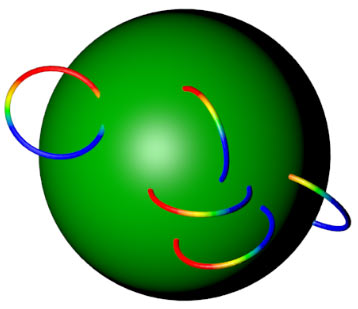

Actually we already know that if these materials are soft, torus surfaces and flat torus surfaces can transform into each other, so we might as well call these things generically torus surfaces. Now all linking methods are: except circles can’t link with circles (they fall off), all other figures can link pairwise. We haven’t mentioned circle-torus surface linking. Actually circles can link with any closed surface because two-dimensional holes and two-dimensional surfaces match perfectly. If you’re still unsure, check their colored projections:

We see green points inevitably exist on circles - tori or spheres can’t be removed from circles. So four-dimensional space necklaces will have two types: one circle with a string of spheres, or one sphere with a string of circles. Note “string” is inappropriate here because circles can slide freely on sphere surfaces without forming strings. The most likely four-dimensional necklace is many small circles on a sphere, because considering four-dimensional beings’ necks should be cylinder-like (one-dimensional lines thickened) with two-dimensional holes, circle necklaces would be unstable.

Could those small rings also be linked? NO! We said earlier that all knots and links in three-dimensional space can be easily unknotted in four-dimensional space. Even if projections show linking, just “shaking” this key chain separates them. So circle linking is unique to three-dimensional space - 4D space has no circle linking phenomena. End of article.

I of course (actually) will end this article like this.