Hyperbolic Space - Mathematical Art

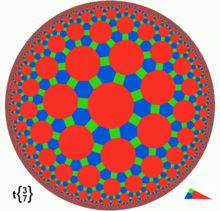

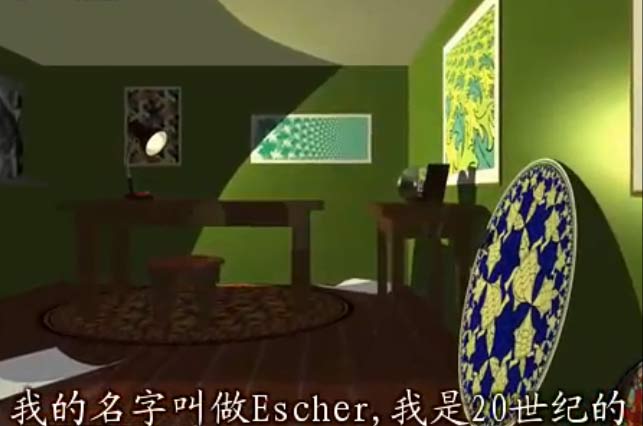

In my previous series of articles explaining “Dimensions: A walk through mathematics”, I mentioned a circular disk pattern that appeared in the film. It was a decoration in the room from Episode 2 “Three-dimensional space” of “Dimensions: A walk through mathematics.” The narrator of this episode is Escher, and both the circular disk pattern and those lizards are his works. The film focuses on telling the story of how one of those two-dimensional lizards escapes from his painting and how it should explain the existence of three-dimensional space to its two-dimensional companions. That circular disk pattern used as decoration only flashes by briefly, but actually this pattern is as fascinating as 4D space: it is hyperbolic tessellation in hyperbolic space.

You can find many of Escher’s paintings online, but the specific mathematical content within them is rarely mentioned. Below we’ll mainly discuss the mathematical meaning of hyperbolic tessellation, and then how we can draw such a painting ourselves - using a computer - online demo here! (including hyperbolic tessellation panda emoji!). Of course, if you’re skilled enough, you can also hand-draw like Escher did!

Hyperbolic Geometry, Euclidean Geometry, and Spherical Geometry

These three concepts should be the most widespread and most introduced online. They originate from the fifth postulate proposed in Euclid’s “Elements”: through a point not on a line, there is exactly one line parallel to the given line. If the fifth postulate holds, we get classical Euclidean geometry (like plane geometry and solid geometry in middle and high school). The most understandable example of when the fifth postulate doesn’t hold is spherical geometry. Lines on a sphere are great circles passing through the sphere’s center (because the shortest path connecting two points on a sphere is an arc of a great circle), and any two non-coincident great circles will intersect at least at two points, meaning no two lines are parallel. Hyperbolic space is the opposite, stating that through a point not on a line, there are infinitely many lines parallel to the given line, where parallel means non-intersecting. Why is it called “hyperbolic” space? Because it’s geometry on a hyperboloid. But the way of measuring distances on this hyperboloid is very strange - it’s the metric of Minkowski space (yes! the same metric used in four-dimensional spacetime!). Under this metric, the hyperboloid is the set of points at a constant distance from the vertex! Beings in Minkowski space (if there were any) would consider the hyperboloid the most perfect geometric body! So we’re not very accustomed to this model.

Poincaré Conformal Disk Model

Just as we can use stereographic projection (remember stereographic projection? Episode 1 of “Dimensions” talked about it) to display spherical geometry, hyperbolic geometry can also project the hyperboloid onto a plane for display. But unlike stereographic projection, the projection of hyperbolic geometry on the plane is confined within a circle. Escher’s circular disk is precisely the Poincaré conformal disk model.

You might say this model looks ugly, with all the surrounding patterns stretched, lacking conformal properties. But it actually is conformal! It’s just that the angles here are hyperbolic angles in Minkowski space! You might not know what hyperbolic angles are, but I think you should be familiar with hyperbolic functions.

When we use a wide-angle lens to adjust the angle to view the entire hyperboloid, at a special angle, the entire hyperboloid appears as a circle. That is, projecting from one point (similar to the north pole in stereographic projection):

Note that like stereographic projection, the projection is angle-preserving (conformal), but this projection “swallows” the special direction reflecting Minkowski space, so the angles in the resulting disk are no longer hyperbolic angles, which is why we can clearly see equal angles. But projection changes the size of figures, meaning these figures are actually all the same size, but the projection makes objects appear smaller the closer they are to the edge of the disk. (Think of perspective projection in life: near large, far small) So this unit disk is actually an infinitely large world! This isn’t hard to understand, because it’s a projection of a hyperboloid, which is infinitely large; while spherical geometry is geometry on a finite closed space. Their essence is a kind of curved space.

From now on, we’ll study the geometry within this disk. Lines in this space are circular arcs orthogonal to the disk, and you can see that through one point, infinitely many lines can be drawn parallel to it.

Hyperbolic Room

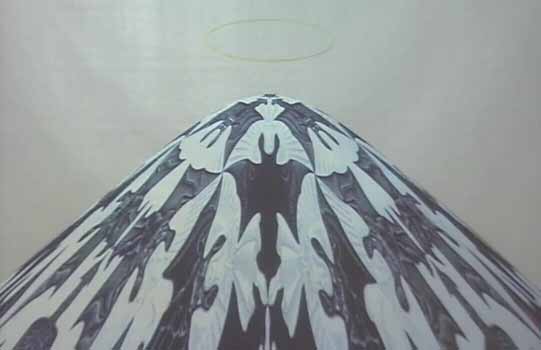

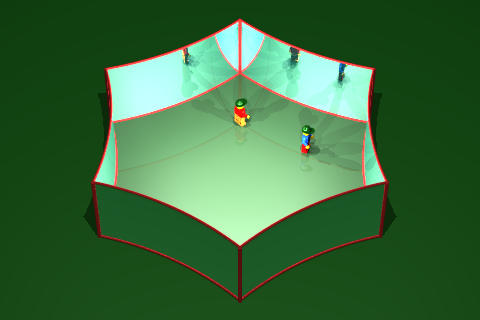

A single empty space is uninteresting and cannot visualize the space. So we can use the method of tessellation (tiling) to tile the entire hyperbolic space with polygons. The result of tiling is what you see in Escher’s paintings. Of course, the edges of polygons in this world are all line segments in hyperbolic space, i.e., circular arcs.

An article “Hyperbolic Chamber“ on the website of josleys, one of the creators of “Dimensions,” provides a way to visualize what beings in hyperbolic space see in their world: replace the edges of polygons with mirrors (mirrors are naturally circular arcs), and then a person standing inside can approximately experience the curved hyperbolic space.

Of course, with two-dimensional hyperbolic space, there naturally comes three-dimensional, four-dimensional… Three-dimensional hyperbolic tessellation visualization can also use this kind of room. For more images, please visit josleys’ article.

Both hyperbolic space and spherical space have constant curvature, so they lack scale invariance. Therefore, except for congruence, you cannot find two similar triangles.

Looking at this, we might have a doubt: exactly how many types of regular polygon hyperbolic tessellations are there? If we want to construct a tessellation satisfying: n-sided polygons, with p edges emanating from each vertex, then we must have:

$$\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{p}<\frac{1}{2}$$

If it equals 1/2, then it’s traditional Euclidean tessellation on a plane. If it’s greater than 1/2, then it’s spherical tessellation. What is spherical tessellation? There are only five types of spherical regular polygon tessellations, corresponding to the five regular polyhedra! The essence of regular polyhedra is regular polygon spherical tessellation! So the essence of regular polytopes is regular polyhedral tessellation on the surface of hyperspheres! With regular polyhedra come semi-regular polyhedra (convex polyhedra with various regular polygons as faces), so hyperbolic space also has composite tessellations of various regular polygons…

According to the previous formula, we can deduce that there are infinitely many types of regular polygon hyperbolic tessellations. The most amazing thing is that hyperbolic space allows the existence of regular infinite-sided polygons! (Note that the regular infinite-sided polygon here is not a circle) If you want, you can even have infinitely many edges emanating from each vertex!

Here we can see that spherical geometric space is a finite closed space, while Euclidean plane geometry and hyperbolic geometric space are both infinitely large spaces, and in some sense, hyperbolic geometric space is larger than plane geometric space.

Möbius Transformations

Remember the conformal transformations using photos before discussing fractals in “Complex Numbers (Part 1)”? Among them, the complex inversion transformation z->1/z is one of the most exciting and fun transformations. Have you ever thought about placing your own photo (or someone you want to prank) on the complex plane and deforming it? We call the linear fractional transformation $(az+b)/(cz+d)$ in the complex domain a Möbius transformation. (What’s the relationship between Möbius transformations and Möbius strips???)

- Translation, rotation, and scaling in our Euclidean two-dimensional space are all Möbius transformations.

- If we consider stereographic projection as projecting onto the complex plane, then the transformation of rolling the sphere on the complex plane projection is a special type of Möbius transformation. In particular, flipping the north and south poles corresponds exactly to the transformation z->1/z!

- If we consider the Poincaré disk model as corresponding to the unit circle on the complex plane, then translations, rotations, inversions, and other transformations in hyperbolic space are all Möbius transformations.

Then you might ask, what should be used to represent transformations on three-dimensional hyperbolic space and spherical (actually four-dimensional hypersphere) space? The answer is quaternion Möbius transformations! Quaternions are four-dimensional generalizations of complex numbers. (Since three-dimensional numbers cannot be generalized, three-dimensional space must also be represented using quaternions, with the extra dimension always set to 0)

With Möbius transformations, we can conveniently draw these hyperbolic regular polygon tessellations using computers. The method is to first calculate the central hyperbolic regular polygon, then through continuous Möbius reflection transformations, like looking in mirrors in a hyperbolic room, copy polygons to fill the entire disk. The specific details won’t be explained in detail here. Josleys’ “Hyperbolic Chamber“ explains the specific approach.

Strange and Wonderful Worlds

Since conformal transformations of photos using complex numbers are interesting, why not transform the tessellated Poincaré disk? Actually, according to the Riemann mapping theorem, any simply connected (no holes) figure can be conformally mapped to the interior of a unit circle, and vice versa.

- Through Möbius transformations, the interior of a unit circle can be transformed to a half-plane (you can think of a circle passing through the pole becoming a line), yielding the half-plane model.

- The inverse hyperbolic tangent function transformation can transform the unit disk into an infinitely long strip, called the strip world: $$B(z)=\frac{4}{\pi}\mathrm{arctanh}(z)=\frac{2}{\pi}\ln\left(\frac{1+z}{1-z}\right).$$

- Finally, based on the strip world, we do an exponential transformation to get an annulus, called the ring world. There’s a science fiction novel called “Ringworld.” $$A(z)=\mathrm{e}^{\Large\frac{i2\pi(z+i)}{kP}}$$

Where parameter P is the period of the strip world in the horizontal direction, so given a tessellation, the period of the strip world is a fixed value. Choosing other values would cause the ring to have a discontinuity that cannot be connected, which also causes the ring world’s isometric transformations to lose one degree of freedom. The integer parameter k can be adjusted freely; it’s the number of strip world periods that appear in one revolution of the ring. The larger k is, the more periods there are, and the thinner the ring becomes.

Inspired by josleys’ another article (in French, suggest translating to English to read), we can modify the expression of the exponential mapping to get a spiral world:

- This website has many spectacular graphics (my favorite is the animation that maps the Poincaré disk to the exterior of a Julia set, I feel I could stare at it 100 times) and also provides some spectacular transformations. I tried to create this: it reminds me of the three-neck flask used in chemistry experiments, so let’s call it “multi-neck flask.” (Please automatically ignore the meaning of freemèrzé)

Online Demo

(I wrote this in JavaScript, best viewed in Chrome browser on a computer, click here to open the demo page separately) Note that in image mode, some graphics cannot be calculated or displayed normally, because I use different algorithms for drawing lines directly and drawing images - one is a direct function, the other is an inverse function, and some inverse functions are multi-valued or cannot be expressed. In image mode, you can load images from your computer. After entering drag texture mode, you can set the image’s position in the central polygon (right-click and drag to rotate and zoom)

Some programs about hyperbolic space I found online

- A small software for visualizing three-dimensional hyperbolic space: Curved Spaces

- You can play Sudoku, navigate mazes, and play billiards in hyperbolic space: HyperbolicGames

- HyperRogue: Highly recommended! (Free download available on official website) The first two are just minor compared to this: a Rogue-like game in hyperbolic space, with infinite maps, various strange biomes (66 types!), and you can fully experience lines, equidistant lines, limit circles, and circles of different curvature in hyperbolic geometry. It trains your pathfinding ability in hyperbolic space - for example, finding the center of a circle with radius 20 cells is more difficult than you imagine. You sometimes discover that hyperbolic space is more like a fractal - a spiral sea where you can never reach the center (based on limit circles), endlessly branching trees with no end, etc. It brings out the geometric properties of hyperbolic space to the fullest in the game, and can be said to rank absolutely first among all two-dimensional hyperbolic games. (Actually, it also supports 3D hyperbolic space and includes other twisted strange spaces like three-dimensional spheres and direct product spaces - the author has very strong mathematical foundations)

It’s worth mentioning its implementation principle. If we use the Poincaré model to store the map, then places far from us would be concentrated in very small areas at the edge of the disk, causing floating-point precision issues. So the author of HyperRogue uses three-dimensional hyperboloid coordinates internally in the program, only doing Poincaré disk projection when finally displaying.

- (2022 update) Hyperbolica A first-person 3D hyperbolic world game. Very clever in rendering and modeling, but in terms of game logic, I unilaterally think it’s far inferior to HyperRogue.

- (2024 update) My own game Deductrium A game implemented in TypeScript in the browser that combines mathematical formal systems with hyperbolic space. Currently includes propositional logic, first-order logic, Peano axioms, ZFC set theory, and some content on ordinals and type theory. The ordinal part makes full use of some interesting geometric properties of hyperbolic space.